Aroldis Chapman of the New York Yankees holds the Guinness World Record for the fastest recorded baseball pitch at 105.1 MPH; a record that has held for almost a decade. Why has no one been able to top his record? — An answer to this question may be found in the biomechanical limits of the human shoulder and elbow during the throwing motion.

As a little background on the subject, the throwing motion can be broken down into six separate phases: windup, stride, arm cocking, arm acceleration, arm deceleration, and follow-through as can be seen below.

Of the six phases only two are the main instances of injury: the arm cocking phase and the arm deceleration phase.

Injury can occur in the labrum and rotator cuff in the shoulder, as well as in the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in the elbow during the throwing motion. In pitchers the stresses are at their extremes due to the unique positions the arm reaches, thus leading to a higher chance of failure in the muscles and ligaments of the arm.

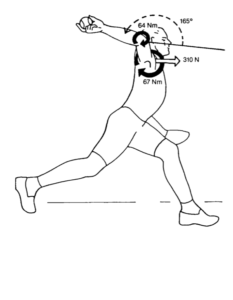

At the end of the arm cocking phase, the arm is in a position of 160° to 180° from the horizontal and puts the arm in the position to accelerate the ball forward. According to one study, extreme torques of 64 N-m and 67 N-m are applied at the elbow and shoulder, specifically loading the rotator cuff and the UCL. Furthermore, the anterior (forward) force at the shoulder of 310 N loads the labrum in such a way that may cause it to tear. The feeling of these loads is equivalent to holding 60 lbs in your hand in the position shown on the right!

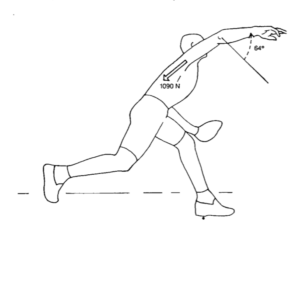

During the arm deceleration phase the arm is in a position of 64° from the horizontal and the shoulder resists the extreme speed and acceleration it just endured. An article showed that during the deceleration phase the arm experiences angular velocities in the shoulder of almost 7,000 degrees/sec making it one of the fastest known human motions. That is about 1,200 RPM which is comparable to the rotational speed of some car engines during cruise control, while traveling at about 50 MPH! Additionally, the rotator cuff and the labrum take the brunt of the 1090 N (245 lbs) compressive force needed to slow down the arm and it is enacted in just an instant!

According to one article, the limiting factor on pitch speed is that the force pitchers apply to their UCL is at the limit of what makes it tear. This means that attempting to throw any faster would result in the UCL tearing! In summary, pushing to gain more MPH on the fastball would mean even higher loads and thus more demand from the shoulder and elbow despite already being at their limits.

All in all, biomechanical data shows that limits in the rotator cuff, labrum, and especially the UCL explain why Aroldis Chapman’s record has been preserved for almost a decade and why the chances of throwing any faster are almost impossible. However, in the world of sports, limits and impossibilities are just waiting to be broken.

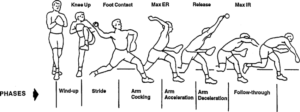

Featured image cropped from “Blue Jays Baseball Pitcher” by George Torok which is licensed under CC BY 2.0.