Many athletes who experience pain right below the kneecap after a spike in volume of explosive physical activities (ie. running/jumping) are diagnosed with patellar tendonitis, commonly referred to as runner’s or jumper’s knee. The suffix “itis” is Greek for inflammation and a common remedy is rest to reduce the inflammation. In some cases, an initial rest period combined with physical therapy to strengthen surrounding muscles such as the hip flexors and gluteus medius is enough to alleviate the knee pain for good, in other cases the rest is of no benefit or even worsens the patellar tendon’s condition and starts a chronic cycle of resting and then returning to activity in more pain than before. In these cases a more accurate diagnosis of patellar tendinopathy is correct. Patellar tendinopathy implies chronically recurring pain on the anterior of the knee that is difficult to treat. In such cases, an MRI often reveals small lesions throughout the patellar tendon indicating that the tendon is structurally damaged and not just inflamed. A better understanding of the patellar tendon’s biological composition, and biomechanical function may help to resolve future cases of patellar tendinopathy.

Understanding Patellar Tendon Structure

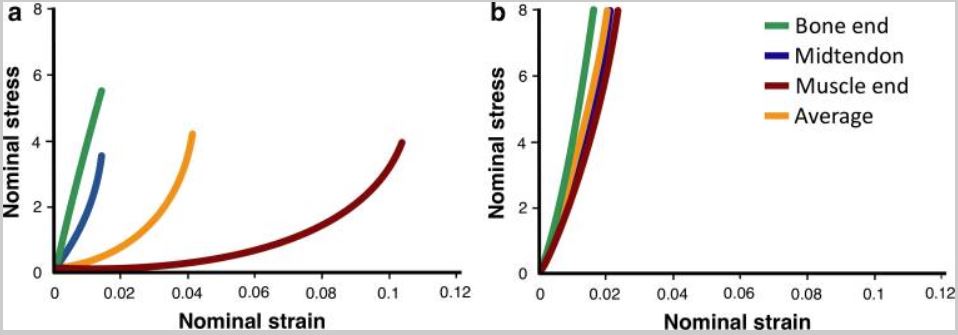

All tendons are viscoelastic, meaning that they display both elastic and viscous properties. The elastic behavior of patellar tendons can clearly be seen in how they stretch when an athlete descends into a quarter squat before jumping and then they contract when the athlete flexes his muscles during the jump. The patellar tendon acts viscously during slow movements, which can easily be felt by isometrically contracting the quadriceps muscle and feeling how the patellar tendon also stiffens. According to research by Keith Baar, tendons are able to behave viscoelastically because of their varying stiffness throughout individual tendons. This varying stiffness helps them to be compliant to the needs of the muscles. Baar continues to state that even just 5 weeks of rest can cause the entire tendon to stiffen and the tendon’s load capacity to decrease. This explains why in cases of patellar tendinopathy resting and strengthening surrounding muscles is not enough to alleviate the pain as the rest causes the tendon to lose its structure and future explosive athletic movements cause additional damage.

Loading of the Patellar Tendon in Slow Movements

During slow movements or isometric contractions the patellar tendon undergoes creep, meaning that the tendon slowly deforms under a constant load. Muscles connected to the tendon are shortening while the tendon itself is elongating. In these instances, the tendon is able to accept more load as it reaches a new steady state. Stress decreases as the tendon reaches its new steady state allowing the damaged portions of the tendon to experience loads that would have otherwise caused pain. This phenomenon is known as stress shielding and tendon creep.

How Does Isometrically Loading the Patellar Tendon Promote Healing and Strengthening to Degraded Tendons?

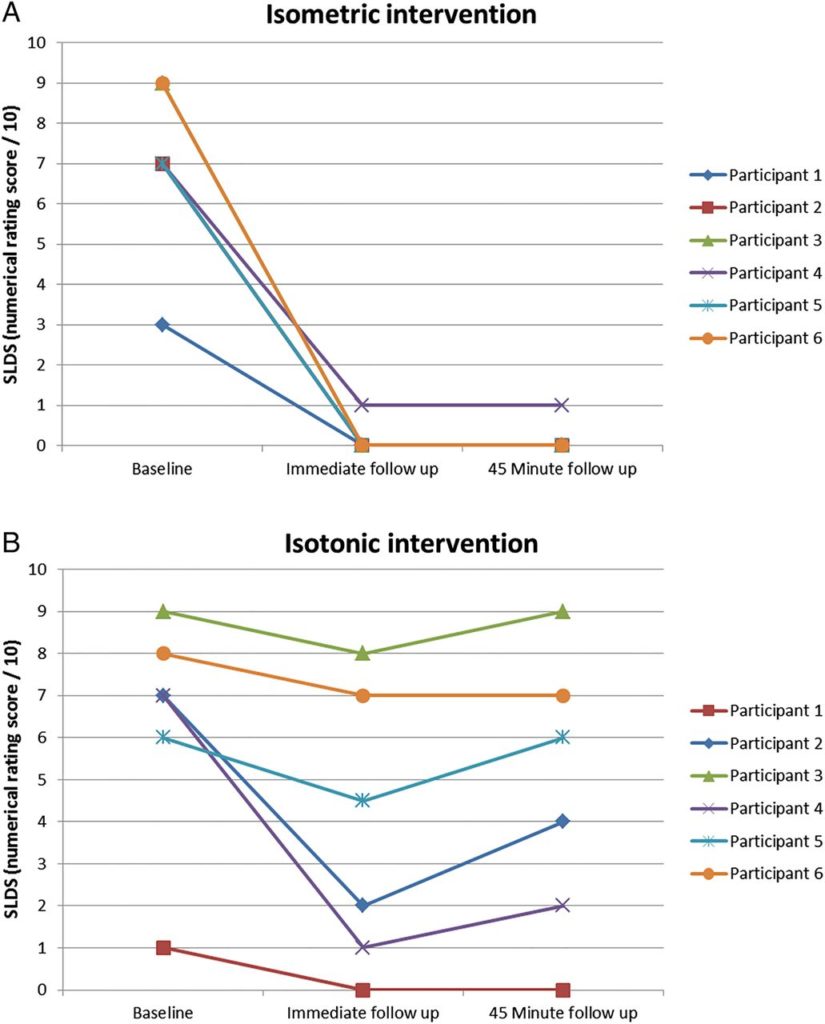

Tendons like muscles strengthen when progressively overloaded. Isometrically loading the patellar tendon presents an opportunity to strengthen an injured tendon without causing pain. In 2015, researchers Malliaras, et al. showed that isometrically loading the patellar tendon at an angle of 55-60 degrees provides the most load to the tendon and thus this angle can be used to force the most adaptation to the tendon without inducing unnecessary stress and pain. A further benefit of isometric loading is the analgesic effect of isometric loading which reduced both cortical inhibition and tendon pain experienced by those suffering from patellar tendinopathy. A study from Rio, et al. showed that when completing a single leg decline squat test before isometric loading and 45 minutes after completing isometric loading the mean reduction in pain levels from patients suffering from patellar tendinopathy decreased from 7/10 to 0.17/10. The figure to the right, modified from Rio, et al., depicts how isometric loading produces even greater pain reduction than isotonic loading. A greater understanding of how isometric loading effects cortical inhibition could unlock new treatment options for those struggling with patellar tendinopathy as cortical inhibition could unlock new pain free ways to load degenerative tendon tissues. An example of a common patellar tendinopathy rehabilitation program utilizing programmed isometric loading can be found here.

Featured image cropped from “Knee pain, leg concept” which is licensed under CC BY 2.0.