by: Nzubechi Pantaleon Uwaleme

How does one move from living “with” the people to living “among” the people without having one’s “otherness” or “foreignness” amplified in everyday life? This and many other questions continued to occupy my mind the moment I began my field experience in Kenya.

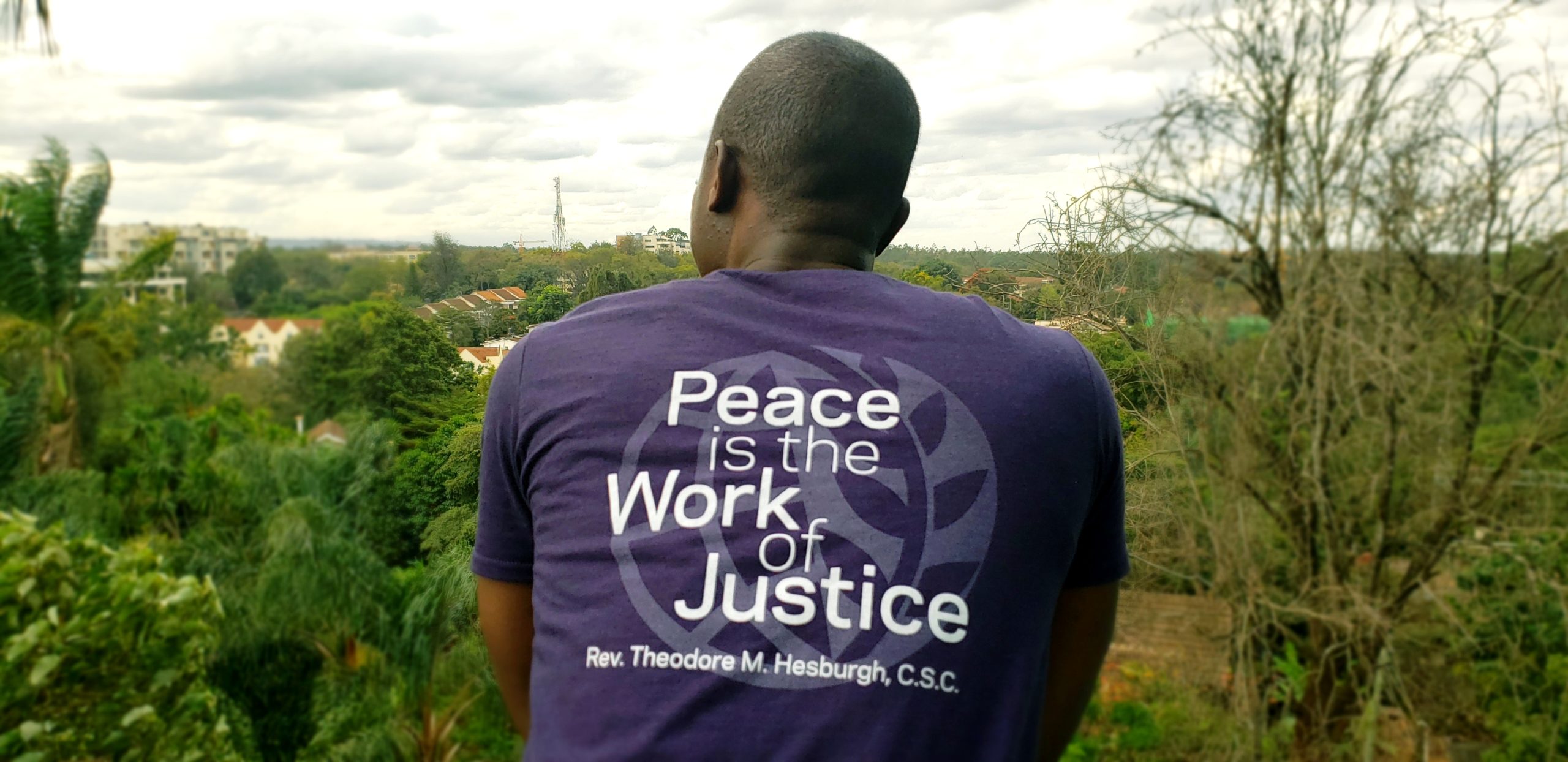

I had learned in my Ethnographic Methods for Peace Research class various ways of navigating the field, taking conscious note of one’s positionality and reflexivity in research contexts. My experience in Kenya has been full of opportunities for reflections and making observations that help to understand how my identity in a particular context shapes events around me. I’m interning with the Life and Peace Institute’s Kenya Program in Nairobi. LPI is an international center for conflict transformation that works in the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes region.

How Sustained Dialogue Prepares Youth For Change

As a non-Kiswahili speaker, I have struggled to interact with young people, the constituents of my field engagement, given their preference for sheng or Kiswahili slang. This is one point where my identity becomes an opportunity for building relationships and friendships, as many of the youth participants at the Sustained Dialogue (SD) sessions (LPI’s pilot program for the youth as drivers of peace) are fascinated by the uniqueness of my name, opening space for interaction and mutual exchanges. Most of my time at LPI is spent listening to young people’s stories, issues, and challenges, and their hopes for a better future. The youth participants at the SD sessions get to spend seven months experiencing the five stages of Sustained Dialogue: The Who, The What, The Why, The How, and The Now! The SD session is designed to enable youth participants to become more aware of their issues, understand each other, and utilize the process of dialogue to transform tense relationships while acquiring skills that will help them shape their future.

In spending quality time with these youth, I have been exposed to the realities of being a struggling young person in Kenya. Many young people in Kenya are facing strained relationships with security forces, especially the police. Some of them emphasized the lack of trust between security actors and young people, which results in profiling, indifference, and extra-judicial killings. There is a high rate of crime involving or suspecting youths. As a result, it has become a norm to categorize the youth population as “unsafe” and “harmful” thereby creating prejudices and biases on the capacity of youth to be agents of change. However, it has become unpopular to look beyond these stereotypes and focus and assess whether every youth is unsafe or harmful as described.

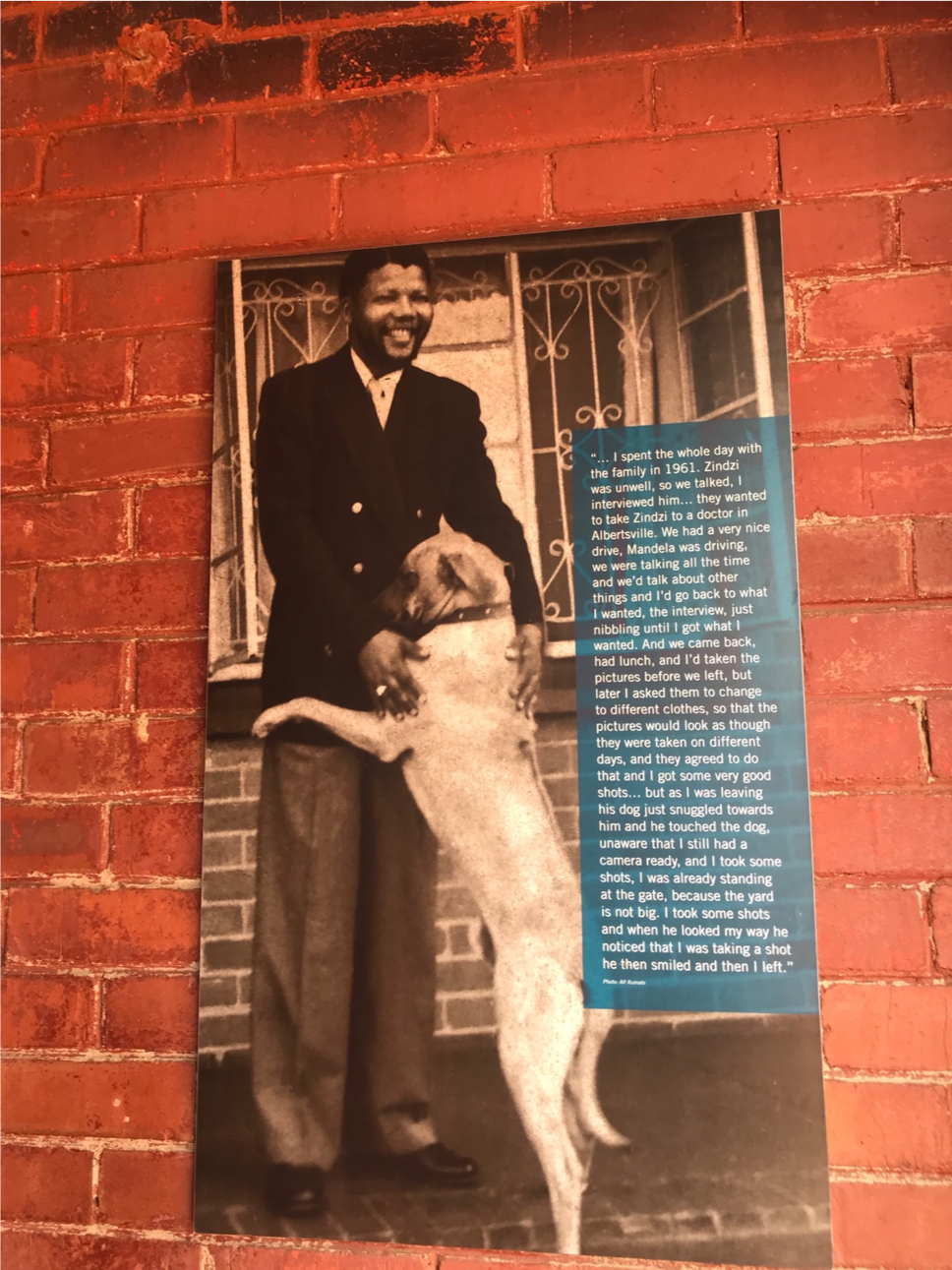

When I look at the long process of SD, the seven months of activities, and how committed these youth have been so far, I wonder why we can’t see the hope in them for a better future. These youth have learned the physical, social, and psychological dimensions of supporting one another. They’ve learned to cope with their peers’ stories of trauma and tackle challenges together. They have learned the process of dialogue and how to be accommodating, tolerant, and supportive of one another. I have realized that when you confront reality, abstract concepts become difficult to talk about but easy to understand.

Transforming Themselves To Transform Others

During this transformative process, I have come to know these youth as “hopeful”. The resilience they have shown through peace actions and community service is one that is born out of a conscious desire for constructive social change. Many of these youth have used the SD sessions to transform themselves from passive observers to active peacebuilders in their communities. They’ve transformed themselves to transform others. Given the diversity of participants, the process has led to changes in attitudes—between Muslims and Christians, different tribes, and the majority-minority divides—thus, building trust and relationships that transcend prejudice and generational biases.

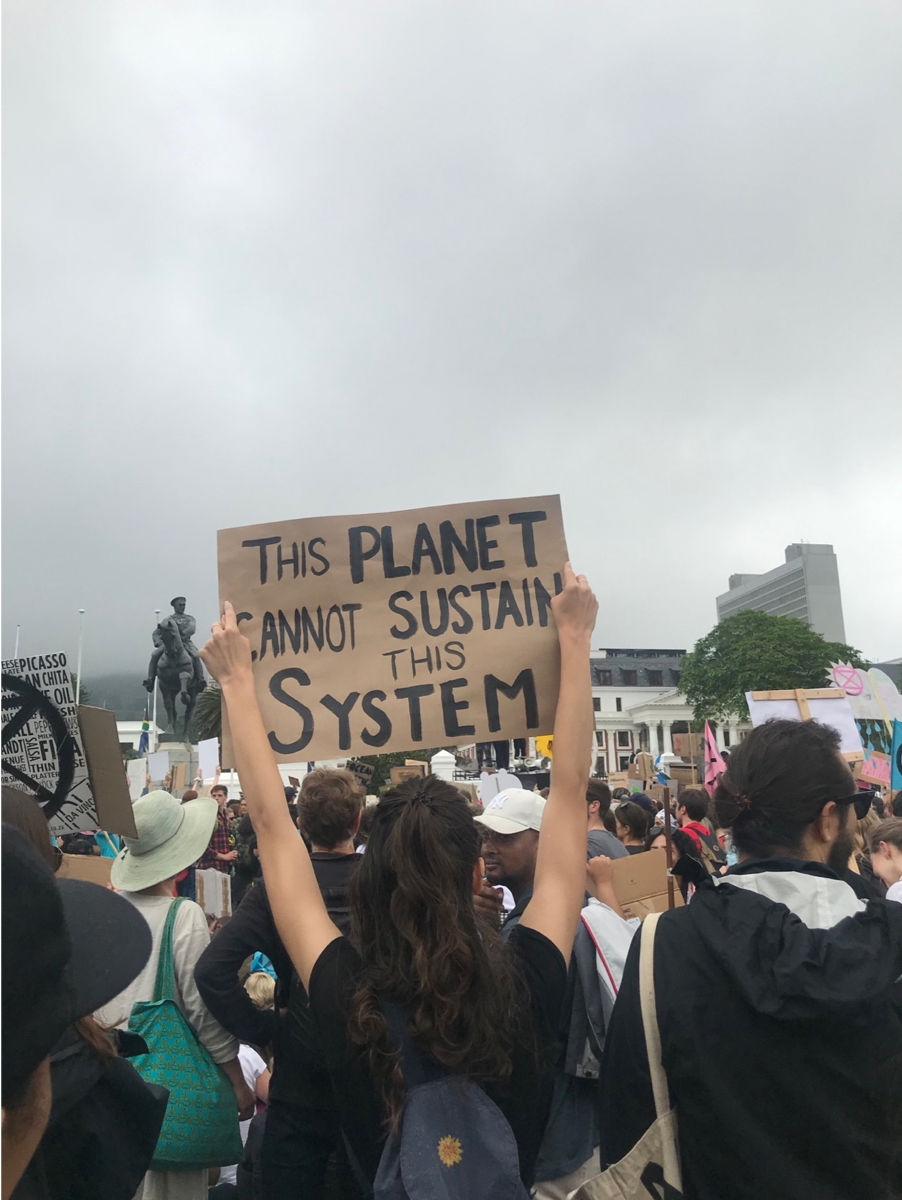

I have participated in many of the activities organized by these youth. They have used graffiti messages to demonstrate hope and encourage their peers to avoid crime; they have provided bins in public places that are targets for waste accumulation; they have planted trees to support climate action and to remind themselves that they are on a journey of growth; they have raised awareness and campaigned against electoral violence in various counties; they have coordinated dialogues for youth in the streets; they have used theatre and other arts to make peace less remote to the local people; and they have equally been involved in resolving conflicts among youth from different communities.

These are various ways the hope-filled youth are driving the wheel of change, bringing their peers together and addressing the local dynamics of youth issues using a local response that propels others into action. Many reformed youth attribute their change of action to the very inspiration they got from the SD participants during their peace actions in communities. Many are expressing how they’ve been lured into the good life by their peers who are hopeful for a better future for them.