“…More like an inquiry. Probing the theory and investigating your interests—for the moment and in time. Seeking the connection and the tension between practice and theory. A search for the location of the individual who is likely impacted and affected by violence and conflict. A rhythmic step toward the hope that the music strums on. An investigation into the connection between psychosocial wellbeing, support, and sustainable peacebuilding.”

This is how I would describe my internship. A curiosity of sorts and a learning process linking me to the work of protection and the relationships therein in a moment to moment movement towards peacebuilding.

I have interned with the Catholic Relief Services EQUIP (Equity, Inclusion, and Peacebuilding) department since July 2019. My focus was on protection and youth in peacebuilding. CRS is a relief and development organization that often works with local partners to promote transformative and sustainable change. Using the holistic approach of integral human development, CRS has programs in agriculture, emergency response and recovery, health, education, microfinance, water security, youth, justice and peacebuilding, and partnership and capacity strengthening.

During my time here, I have engaged in both policy formulation around protection issues and advocacy on upcoming Youth, Peace and Security legislation while leaning a lot on my policy analysis lessons at the Keough School. I was based in the Baltimore CRS Headquarters and had proximity to Congress in Washington, DC.

An invitation into planning and design transformed to participation in formulating guiding principles for organizational and humanitarian response in protection and prevention from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA). We explored the role of language and culture in PSEA when working in communities. In a field that works with communities towards change, language and culture often determine the expression of violence and, consequently, the social transformation. What does this mean for organizations that choose to use the official languages in multilingual and multicultural countries? Or even the big four languages—English, French, Spanish, and Arabic—in global contexts? By creating a language criteria to promote inclusion, who gets excluded in the communication?

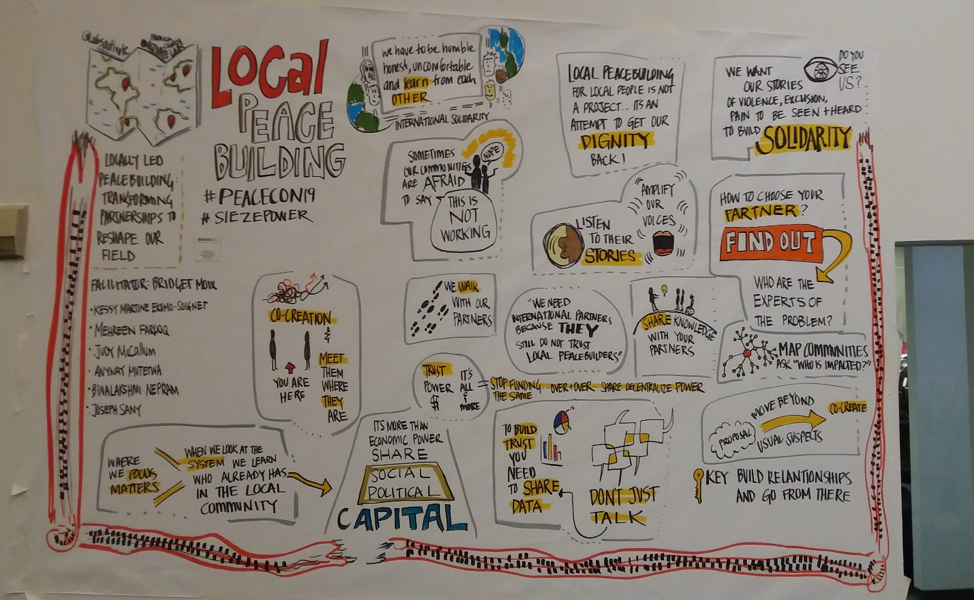

I believe an anthropological reflection would give insight here. The outcomes of this process established the need for incorporating more languages into our roles in community engagement and a survivor-centered approach to acknowledge the asymmetry in agency and power for the vulnerable and affected communities. We must recognize the gender and resource interplay in the conflicts that can get hushed in the search for survival. Everyday. The discussions expressed the importance of focusing on prevention and indicated that when the focus is protection, the root cause is yet to be addressed. Ultimately, the policy called for the need to listen to the local, not just for “box checking,” but with the intention of yielding power and co-creating change to support the human security of survivors.

As CRS adjusted its strategic plan, I had a didactic experience reflecting on the visioning and implementation of peacebuilding into different programming initiatives. What would strategic peacebuilding look like, for instance, in health and gender focused initiatives? Given that implementers at the community level were involved in this process, the relationship and, in some cases, the tension between practice and theory was evident.

As the different actors held this tension with both curiosity and openness to experiment with an idea, I was encouraged. You see, as a learning peacebuilder, I am aware that we certainly do not have the answers or solutions to the violence and conflict in our world today. By all means, we try, we show up, we ask questions and seek to hear how communities and people envision peace. Then, we accompany the process and the people, we implement the ideas, and sometimes we build and inform the idea through feedback and functional relationships in that space. It sounds simple, but so does a surgical process on paper. Until you begin the dissection and realize that this is an intricate process needing attention, skill, listening, and presence with human beings—all at the same time and in an appropriate environment. And conflict and violence are not predictable.

When I began the examination of the implementation of the Singing to the Lions workshop, I found myself often interrogating the political, social, economic, and cultural contexts of the participants. Singing to the Lions is a psycho-education workshop to build resilience and foster social cohesion among children in contexts of violence and conflict. When noticing resilience in a community, we also need to look at the local and shared underlying structures making them resilient and reinforcing them toward sustainable peacebuilding. This provides the appreciative inquiry into how well the environment fosters the individual’s psychosocial wellbeing and possibilities of sustainable peace.

In this process, I found that although the target audience is children, depending on their context and needs, different implementers have “cherry-picked” what works for their contexts and other identities (age and role). Certainly, this modification impacts how the evaluation of such an approach works, even with a preexisting monitoring and evaluation process. What would contextual indicators look like from the perspective of the individual in this case? Please ponder with me here.

Finally, I wonder, “what, who and how” have I become as a nascent peacebuilder? I don’t wish to get lost in the process and emerge without a soul in the end. I am grateful for the community of colleagues that held me in the learning and the inquiry. I am present to the local communities where my feet journeyed for this transient time. As I reflect with hope for those who continually work and seek change, I join you all in the reflective practice, in the study, and in being.