Glittering lights and high-rise buildings rushed past my view as I looked out the window at Dubai, my home for the next ten days. I was here to attend the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference, known more broadly as the Conference of the Parties (COP), as part of the Christian Climate Observers Program.

COP is a unique experience in that it brings together some of the most prominent diplomats and political figures worldwide to intermingle with registered representatives from civil society groups, universities, and other advocacy organizations.

Each year, diplomats from most countries come together to discuss current international policy and research on climate change. This is the place where dreams can become reality; where ideas can coalesce into concrete policy. Just as easily, though, these calls can be blunted by long hours of consensus-based, painstaking negotiations that fill them with loopholes and vague promises.

Climate and reparations

COP28 this year was, in many ways, the culmination of my undergraduate work. I began to focus on climate change at Notre Dame when I realized the great extent to which it was destroying lives and livelihoods around the world in the present-day. For much of my life, climate change was a far-off issue with its real and devastating effects obscured by technocratic discussions of emissions targets, parts-per-million of CO2, and energy efficiency. My work in the Notre Dame Reparations Design and Compliance Lab taught me otherwise. I learned that the rising sea levels and more frequent and severe storms caused by climate change were already driving ever-increasing numbers of people away from their homes. I became deeply passionate about hearing these stories and bringing them back to my communities through my research in the Philippines, where civil society advocates, Indigenous peoples, and local leaders graciously shared their experiences of climate change and thoughts on climate reparations with me.

Small island states

I brought this passion with me to COP28. Going in, I was hoping to learn more about the human impacts of climate change that were rarely discussed in my home communities. Of particular interest to me were the small island states. These places face an imminent, existential threat to their people and culture in the form of sea level rise—as global warming worsens, the average planetary sea level increases, threatening to permanently bury these low-lying islands. I was generally familiar with this issue but, despite my effort, found little opportunity as a Notre Dame undergraduate to hear the firsthand stories of those impacted from across the world.

As I had hoped, I met a number of incredible individuals from these diverse areas, who shared with me the complex wealth of experiences that brought them to COP. I learned more about the valuable contributions of Indigenous knowledge in the fight against climate change. I was introduced to the efforts spearheaded by Vanuatu and other small island states to have the International Court of Justice clarify states’ legal obligations on climate change.

What inspired me the most, though, was the resilience and tenacity they all showed in the fight for climate justice. The small island states were consistently at the forefront of international efforts to combat climate change, the strongest voices pushing the most comprehensive solutions to the problems they faced here and now. They were not powerless victims of an unfair fate forced upon them by environmental sins mainly perpetrated by the highest-emitting countries. They were, as the Pacific Islanders called themselves, warriors.

This spirit of determination ran through so many others I met, as well. I came to know many of the youth delegates representing Australia, who showed me the many different ways young people can approach the climate crisis: wildfire monitoring, advocacy through art, powerful speeches, and so much more. I met with civil society actors from the Philippines whose empowering stories gave me a more complete picture of the adversities they faced in their work. Intense conviction in the wake of countless policy setbacks united countless people from across the world at COP28, a unified spirit that gave me hope that we truly can fight effectively against the climate crisis.

From hope to action

This hope, though, is only the first step. We need concrete action—not just promises—to protect our lives, our livelihoods, and our common home, not only for ourselves but for future generations. We need to recognize that climate change is not something to be avoided in the future, but something that is already upon us. Now more than ever, I am aware that climate change is not merely a scientific issue but is, importantly, a deeply human one, as well.

At Notre Dame, we are fortunate to be relatively sheltered from severe climate change impacts now. This does not mean, however, that it will always be this way, nor should we ignore how these impacts harm millions of people around the world in the present day. We need to create spaces on our campus where these voices can flourish and be heard, because caring for our common home means engaging with and learning from those who are at the forefront of fighting the threats against it.

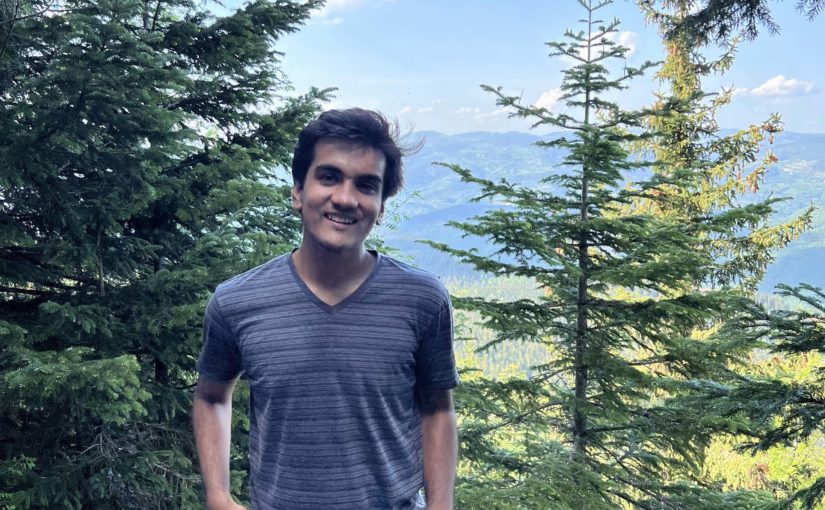

Garrett Pacholl is a Notre Dame senior studying history and global affairs.

Top photo: The author under the main dome of Dubai Expo City, where COP28 was being held.