by: Laura Guerra and Shadwa Ibrahim

When we planned for the summer as master of global affairs students, we expected to have rich in-person field experiences in South Africa, Tunisia, and the Philippines. Some of us even contacted family and friends in these countries and made arrangements to see them. We devised our research plan using methods like focus group discussions and human-centered design workshops—methods that, we hoped, would help to improve development outcomes within the private sector.

But the surprise of a global pandemic disrupted all of these plans, prompting us to adapt and ultimately pivot to online fieldwork. This gave us a chance to test our assumptions and expectations about fieldwork, learn about ourselves as individuals and as a team, and experience an enriching partnership with Chemonics International that will still contribute to better involvement of the private sector in achieving development outcomes.

Originally, our i-Lab team expected to work with four projects in three countries. Throughout the spring semester, we discussed preliminary ideas about our plans for working together in the summer. However, the outlook became gloomier in April, and this continued into May, when we were to begin our fieldwork.

We started our pivot towards virtual fieldwork in mid-May with only two projects out of the four ready to work with us. We were doubtful about the feasibility of using our initial toolkit, confused about our next steps, and questioning the value of any work we would produce in this remote work mode. We spent hours discussing our assumptions and fears internally as a team, with our advisor, Melissa Paulsen, and with our partner liaisons, Chemonics’ Universities Partnerships Team. These open conversations helped us reaffirm our commitment to the project and prepared us to change our outlook on uncertainty and equip ourselves for the many potential scenarios and directions the project might now take.

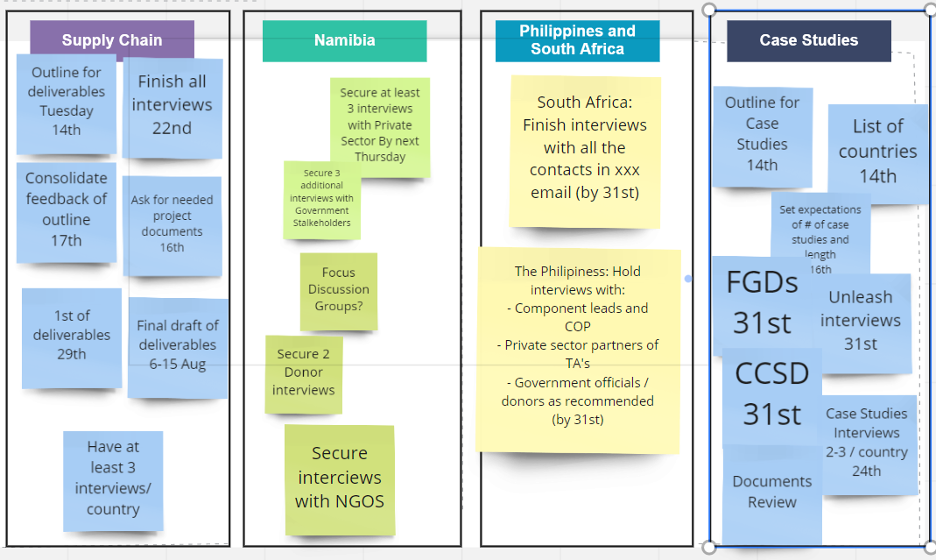

We started by revisiting our action plan and intended methods of data collection. We agreed to do so regularly and update our plan and methods vigorously as we moved forward. We started by prioritizing our Private Sector Engagement (PSE) in-depth survey for the PSE practices within Chemonics as an organization to formulate our understanding of the needs of our partner. The survey had a high response rate and received input from 28 different ongoing projects in 42 countries. The results of our survey informed our project plan and were helpful for Chemonics to realize where their field staff faces bottlenecks when it comes to PSE, as highlighted in this blogpost on Chemonics website. Based on the survey, we decided to focus more on Key Informant Interviews and desktop research as our primary tools for data collection and deliverable formulation. In this task we collaborated closely with the Chemonics PSE SMART Team.

At the same time, our partner, Chemonics, worked with us to ensure that this was a rich learning experience for us. As a result, we included two short-term PSE focused projects with different deliverables for the health supply chain team within Chemonics and another project in Namibia involving water delivery and maintenance systems. So instead of the initial four projects we had in our proposal, we ended up engaging closely with five projects and teams in eight different countries and had four final deliverables instead of one! It is important to note that we worked extremely hard to guarantee that the quality of our work was consistent and exceptional throughout the different components of our project. The task was challenging, especially with our four team members being in four different time zones, with up to a 12-hour difference. All of this was possible because of those conversations we had early in the summer, where we decided to reach beyond our expectations of how our summer should be and focus on adapting to what our summer actually was.

Below are four lessons we learned from our remote i-Lab field experience.

Accepting Uncertainty and Celebrating It

One of the biggest challenges that we experienced as a team was getting comfortable with the uncertainty of how our project would continue unfolding. It is worth mentioning that this did not mean we waited for things to happen to improve our outcome magically, but rather became completely okay with what might happen next. To do this, we focused on distinguishing between the things within our reach and those outside of our control. Once we made this distinction, it was easier to make a plan and take concrete steps to reach our objective. Recall that when we first started our i-Lab project, we prioritized our data collection on projects that were ready to work with us and co-designed an in-depth analysis survey that guided us on how we would shape our final deliverable. Once we analyzed the results of our data survey, we learned that our partner’s top need was to provide successful examples of PSE in case studies format. This finding guided our next steps.

Practicing Open Communication

Our next key takeaway from our fieldwork was the importance of open communication in all aspects of our project. This helped us align expectations within our internal team as well with our partner. Sharing our challenges and fears openly and immediately allowed us to find solutions to any arising issues instead of delaying conflicts that could jeopardize the quality of our project given our 9-week constraint. Being intentional about communication definitely challenged us outside of our comfort zone, as some of us were intimidated to vocalize concerns and disagreements. Still, it paved the way for us to meet deadlines and adapt our strategy to accomplish the objectives of our fieldwork. For example, our team was split between specializing entirely into different lead roles and keeping lead roles but sharing a smaller degree of responsibilities in other projects. After communicating this concern, we were able to come up with a compromise that allowed us to each focus on a lead project, but continue to support our teammates. What also made this much easier was that our liaisons were very understanding and receptive to our concerns. They validated many of these concerns and worked with us closely to address them throughout the summer.

Working Remotely And Creatively

Working remotely did not mean we could not collaborate creatively. Our team learned to use different collaborative tools to foster creativity and inclusivity internally and externally. Even working remotely, we were aware some of us were more comfortable voicing ideas than others, so reaching a consensus that truly reflected everyone’s opinion could be difficult. However, we were intentional about using online tools that allowed everyone to participate and make our sessions more engaging/interactive. One form of collaboration we used was GroupMaps during a stakeholder mapping session we held with our liaison from the South Africa team. This allowed us to brainstorm in real time and then as a group discuss the rankings of the key players and prioritize key stakeholders for interviews. Using these tools helped us make our decision-making process more effective and even fun.

Leaning into the Team

The last takeaway that resonated with our team was the value of leaning in. While we worked from four different time zones, we were able to support each other in times of need. We conducted interviews that took place at 4 a.m., and thankfully, we could count on each other to take turns and perform these in pairs. We were intentional about dedicating a space to check in during our weekly meetings and even followed up after long days of work to see how we were doing.

This value of leaning in pushed us to ask for a support system when we most need it. For instance, when we faced barriers or roadblocks securing Key Informant Interviews in Namibia, we leaned into our partner in South Africa to leverage networks that ultimately enhanced the quality of our research and led us to our targeted interviewees.

Looking back at our summer fieldwork, we cannot help but smile. We smile because of how optimistically we thought things would unfold for us. But we also smile because we are proud of how we made things work for ourselves despite the obstacles and made this past summer a richer learning experience than we could ever imagine!