“Civility, respect, and a return to what’s important; the death of bitchiness; the death of gossip and voyeurism; speaking truth to stupid.”

This quote comes from HBO’s The Newsroom, the best TV show about journalism in my opinion. Six years ago, when I started watching the very first episodes of The Newsroom, I had not even embarked on a journalistic path, but I was impressed with the inner world of the journalistic profession as described by writer Aaron Sorkin. This world was about truth, credibility, and respect, three goals that I strive to pursue in my career.

Trying to find a perfect field placement to study ways of resisting Russian disinformation and propaganda, I focused in on international news organization Voice of America (VOA). According to its charter, VOA’s purpose is “presenting a balanced and comprehensive projection of significant American thought and institutions.” For the last 76 years, VOA has produced content in more than 40 languages. Luckily for me, combating disinformation is one of the principles of the VOA’s day-to-day work.

VOA was founded during World War II to combat Nazi propaganda through unbiased and accurate journalism, and today, with the rising of a new propaganda evil and ongoing information wars, it’s probably the second most important time in the VOA’s history for the organization to live out its mission.

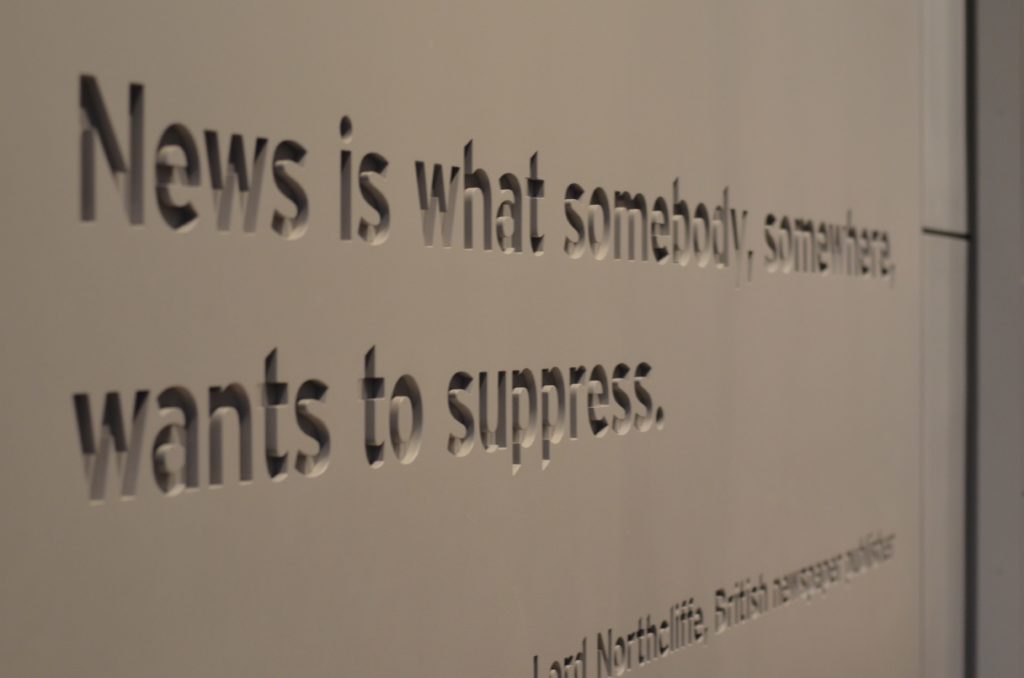

In today’s world, objective, truthful and bias-free information is crucial for sustainable peace and journalism itself can be seen as a form of peacebuilding. Sometimes it feels like “liberal peacebuilding” when journalism is used as a tool against crimes, corruption, disinformation and hybrid wars. At other times journalism can be portrayed as “sustainable peacebuilding,” when the truth is used for the purpose of healing and reconciling.

I have spent some time (ok, too much time) trying to figure out the format of this blogpost. But, as you may observe from its title, I focused in on one day in the life of the VOA’s Ukrainian newsroom. In the best tradition of VOA’s blogs, I’ll try to keep this blogpost short, but thoughtful. So this is a 4-minute read. Let’s get started!

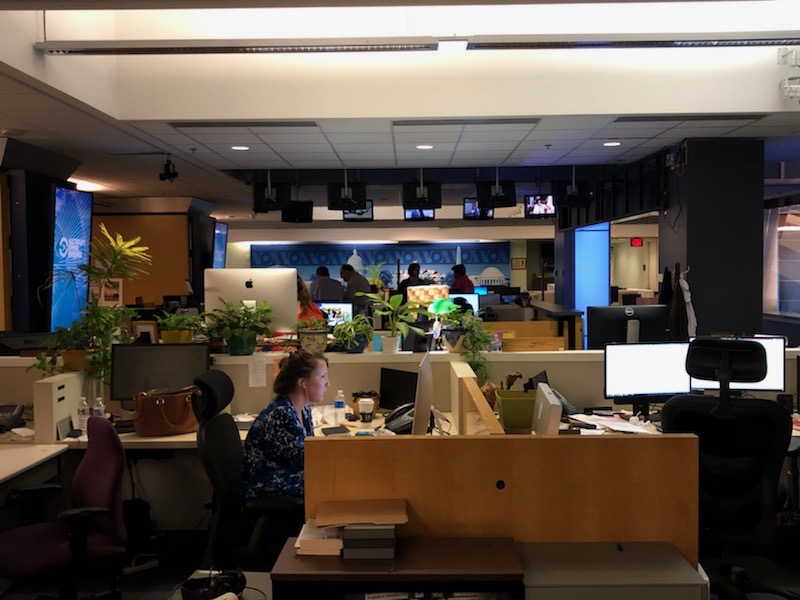

8:30–9:00 a.m.: The bright and totally over-air-conditioned office is filling up with journalists. I have a feeling that coming from Eastern Europe, I can adapt to everything except AC levels in the U.S.

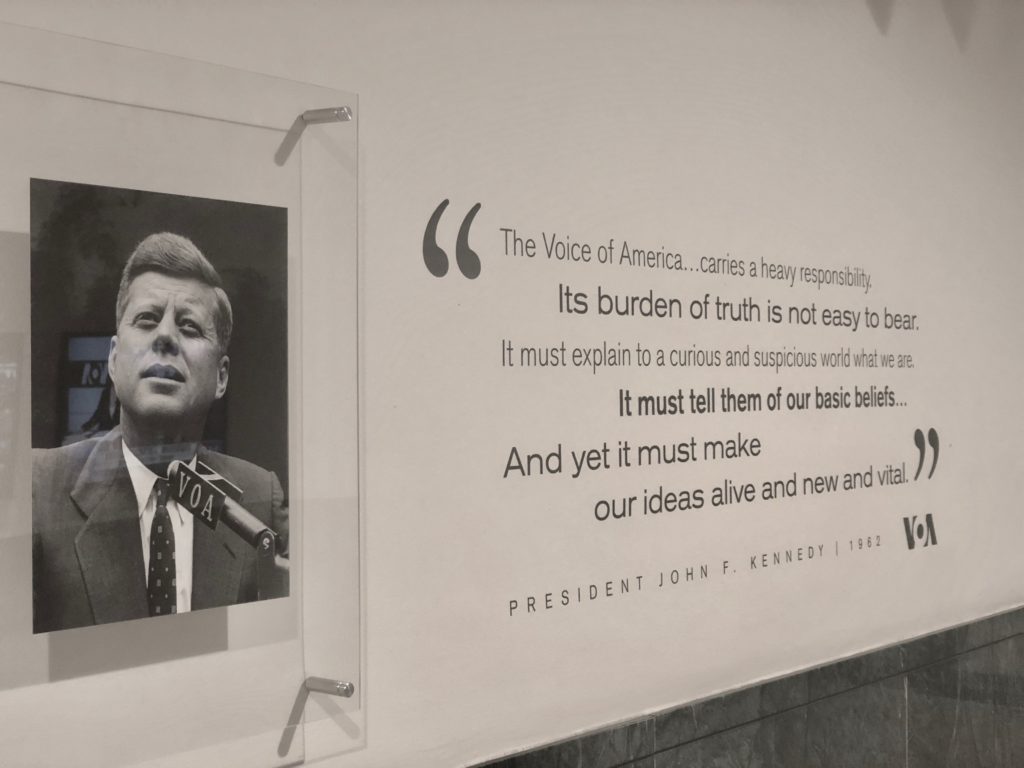

At the entrance of the federal building, employees are welcomed with John F. Kennedy’s quote: “The Voice of America…carries a heavy responsibility. Its burden of truth is not easy to bear.” Meanwhile, the building itself has five stories above the ground floor. The last one is a mess of hundreds of studios and broadcasting rooms where one can get lost.

9:00–9.30 a.m.: Normally you have two goals for this half hour: you need to find a story (if you haven’t found one yet) and stay caffeinated.

Web journalists are looking for the stories to be published on the website, TV journalists are choosing topics which will go on air after less than 5 hours, so time is ticking.

Summer is a perfect time for most of the interns to fill the gap and show what they can do while staff members are on vacations and VOA might need your help more than any other time. Since the very first day when I finished my paperwork, I’ve been treated as a full journalist, working five days a week from the first cup of coffee in the morning to the time when the work is done. I feel lucky that I have had a chance to participate in every single level of content production. From browsing the servers and watching incoming news feeds, to doing in-depth research about the most important ongoing investigation in the United States, from providing a voice-over for someone’s soundbytes and on to spotlighting disinformation in Ukrainian media.

9:30-10.00 a.m.: It’s a time to pitch your stories.

During the editorial meeting, you have a few minutes to pitch your story, answer tough questions, and prove that the story is worth the team’s time. If the topic is strong enough, after the editorial meeting you will start working on content production, trying to meet the deadline. The deadline is everything. Deadlines differ for different stories, but for web news stories (which is most of what I write), the deadline is always “now.”

10:00–2:30 p.m.: Work like crazy.

These 4.5 hours are really varied for the different teams in our newsroom. TV journalists are working on their stories for the air and content and video editors are trying to make these stories look perfect. Someone is often in the field, shooting new content. Someone is adapting Reuters or Associated Press stories. Someone is making voiceovers. But at 12:00, it usually becomes hot. You must be on time and you must produce meaningful content with broadcast quality sound and picture.

The web team normally has a reasonable time to publish news articles, but it’s breaking news, it’s all about time. You can’t wait, you can’t hesitate, and you can’t be slow. After just a couple of minute,s the story may lose all its value. But even in breaking news situations and even if you are a journalist with 10 years of experience, you cannot press the “publish” button without your editor or another person in the office fact-checking and proofreading your story. This is how you earn your audience’s trust.

2:45–3:05 p.m.: On air

It’s the most stressful time of the day for editors, journalists, and producers. Everyone feels equally responsible for any problem that arises. When the hosts and the producer are going down to the studios, anything can go wrong: equipment isn’t working, the picture freezes, the network connection is slow. But, at the moment the anchor says, “Good afternoon. This is VOA Ukrainian’s daily show, Chastime,” usually everything flows as it should. None of the viewers can feel the tension on the other side of the blue screen. No one except an intern, who now feels more engaged than just a regular observer.

3:05-5.00 p.m.: A time to breathe

When the most stressful part of the day is over, both for the TV and web teams, you have time to work on your in-depth articles, feature stories, and anything that does not fit under the deadline “now.”

During the first month of my internship, I mostly worked for the website, producing analysis, news pieces, and infographics. I covered the topics of Russian meddling in the U.S. elections, Kremlin disinformation and hacking attacks, and the Mueller investigation. And a solid multimedia story written by me about the Ukrainian side of the Russian interference investigation was recently published.

But I guess my 4 minutes are over for now, right?