A few years ago, the Medieval Institute launched a new scholarly initiative. Designed to highlight the wealth of scholarly information here at Notre Dame while increasing scholarly community and cross-communication across disciplines and ranks, the Medieval Institute Working Groups were established as a means of creating such an academic crossroad.

One of these groups, Religion and Pluralism in the Medieval Mediterranean, sought to push against the popular image of the Middle Ages as a uniquely Western European Catholic phenomenon. The organizers, Dr. Thomas Burman (Director, MedievaI Institute), Dr. Gabriel Reynolds (Professor, Theology) and Andrea Castonguay (Ph.D. Candidate, History), believed that by shifting the geographical parameters from Northwest Europe to the Mediterranean basin and opening up the confessional borders of scholarly investigation that had previously segregated the Middle Ages into self-contained Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Jewish, and Muslim spheres, the Working Group would bring new perspectives to the idea of the Middle Ages and facilitate an interdisciplinary approach to the period. If a topic was somehow tied to the peoples, cultures, and civilizations active in the Mediterranean at some point during the Middle Ages, the Religion and Pluralism Working Group judged the topic fair game for discussion, inquiry, and exploration.

While this rubric for a field of critical inquiry might be seen by some as generous to a fault, its breadth is actually the Working Group’s greatest strength. By casting a wide net, the Religion and Pluralism Working Group attracted a diverse group of members and speakers, most of whom would not necessarily interact with one another in an academic setting outside of a social hour.

During our first year in 2017-2018, we hosted 8 sessions where the topics of discussion and the presenters themselves reflected the group’s diverse make-up. The inaugural session was led by Dr. Jeremy Pearson (Bryant University), then a postdoctoral fellow at the Medieval Institute, who presented an article on William of Tyre (d. 1186), an archbishop and Dominican friar of European origin born in the Crusader kingdoms and privy to a unique perspective on the interplay between European Christians, Levantine Christians, and their respective relationship to the life of the Prophet Muhammad. Although not by design but by happenstance, the Working Group continued to focus on Christians in the the Middle East and how they responded to Islam during Fall 2017 by reading Michael Penn’s Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World (UPenn, 2015) and hosting Dr. Jack Tannous (Princeton University) for a lecture and discussion on Syriac Christian sources and their importance for understanding the early centuries of Islam, the establishment of the Umayyad (661-749/750) and Abbasid caliphates (749/750-1258).

During our Spring 2018 sessions, our attention turned to other parts and peoples of the Mediterranean and other types of scholarship. Whereas our Fall 2017 sessions focused on using religious texts to understand historical events, our Spring sessions turned to the ways in which different types of physical evidence, from archeological records, material culture, personal journals, could tell us about the medieval past. Dr. Sarah Davis-Secord (University of New Mexico) joined us for a discussion of her book, Where Three Worlds Meet: Sicily in the Early Medieval Mediterranean (Cornell UP, 2017) and spoke about the pros and cons of reconstructing centuries of history from physical objects in the absence of written records. Eve Wolynes (Ph.D. Candidate, History) presented a chapter from her dissertation on Venetian and Pisian merchant families and the various differences between Italian merchant families and commercial practices during the Late Middle Ages that her source material revealed over the course of her investigation.

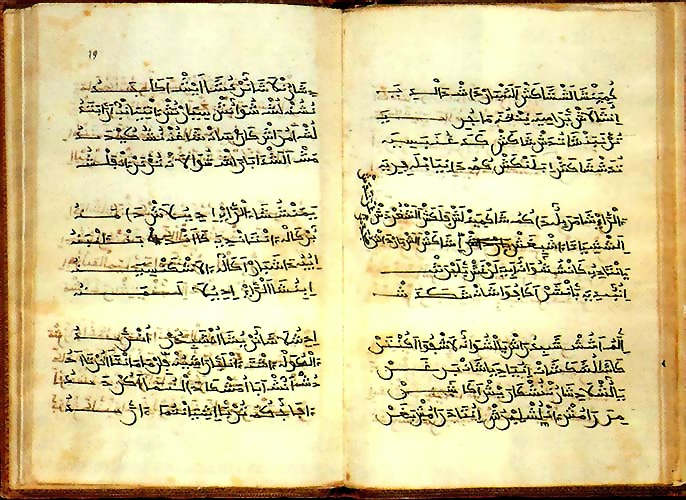

Last but not least, the three co-organizers of the Religion and Pluralism Working Group, Tom Burman, Gabriel Reynolds, and Andrea Castonguay, all took turns presenting various works-in-progress to the group. Gabriel Reynolds presented book chapters on sinners and sin in Islam from his forthcoming book, Allah: A Portrait of God in the Qur’an, while Andrea Castonguay presented a dissertation chapter on Muslim dynasties and competing Islamic sects in early medieval Morocco. Tom Burman closed the 2017-2018 year by presenting with Dr. Nuria Martínez de Castilla (École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris) and Dr. Pearson the fruits of their collaborative project on the purported correspondence between Byzantine Emperor Leo III (r. 717-741 ) and the Umayyad caliph ‘Umar II (r. 717-720) and its dissemination in Latin, Armenian, Arabic and Aljamiado (medieval & early modern Spanish languages written in Arabic script) literature during the Middle Ages.

As the Working Group moved into its second year, its members sought to keep up the momentum while upholding the group’s commitment to rethinking the traditional academic boundaries of the Middle Ages. Noticing the lack of sessions devoted to Byzantine scholars and studies during the previous year, the members of the Working Group rectified that by asking the resident Byzantine postdoctoral fellows, Dr. Lee Mordechai and Dr. Demetrios Harper, for their recommendations. As a result, the group read Phil Booth’s Crisis of Empire: Doctrine and Dissent At the End of Late Antiquity (UCalifornia, 2017), which explored how monasticism, initially a very vocal way of rejecting centralized power and empire, became an important component of both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Byzantine Empire during the 6th and 7th centuries. In addition, Dr. Paul Blowers (Milligan College) was invited to speak about the interplay between the pre-Christian Classical world and the Christian Byzantine world in theatrical literature. Issues related to the Byzantine world and its relationship with the former Roman Empire were also discussed during a presentation by Dr. Ralf Bockmann (German Archaeological Institute Rome; Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton) by way of changes to church structures and saint veneration in Christian North Africa during the transition from the Vandal (435-534) to the Byzantine (mid 6th- mid 7th century) period.

In a similar vein, the organizers sought to diversify the Working Group’s membership by reaching out to new members of the wider Notre Dame and St. Mary’s community and asking them to present their research. Dr. Hussein Abdelsater, a new member of both the Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies Department and Medieval Institute Faculty Fellows at Notre Dame, presented a paper on the miracle of the splitting of the Moon and the ways in which it was discussed in Qur’anic exegesis. Dr. Jessalynn Bird (Humanistic Studies, St Mary’s) presented early work on Jacques de Vitry (1180-1240) and and Oliver of Paderborn (fl. 1196-1227) as part of a new book project on Mediterranean geography in the writings of Western Europeans. Dr. Robin Jensen (Patrick O’Brien Professor of Theology) gave a presentation on the tension between early Christians, their adherence to the commandment to have no false idols, and the presence of Classical deities and statuary in the Late Antique Mediterranean landscape.

Moving outside of the South Bend community, Dr. Mark Swanson (Lutheran School of Theology, Chicago) was invited to speak about the ways in which Copts in Mamluk Egypt read various Arabic works such as the writing of Moses Maimonides (c. 1135-1204) and the Pentateuch of Saadia Gaon (c. 882 -942) and incorporated their ideas into Copic liturgy and liturgical writings. This presentation along with Dr. Swanson’s generous show-and-tell of publised Coptic primary sources was especially interesting to several upper year Theology Ph.D. Candidates working on Near Eastern Christian communities, who were pleased to learn more about the various resources available for the High and Late Middle Ages.

From its inception, the goal of the Religion and Pluralism Working Group was to bust down the various walls that silo academics and scholars into a specific discipline while reminding others–ourselves included–that the Middle Ages was a long historical period encompassing many different civilizations, peoples, faiths, and geographies, and that we need that multiplicity of specialists in order to understand this period in history. There is no such thing as a medievalist who can act as the sole representative of the discipline, nor can they bear the discipline’s weight all by themselves. Rather, there are medievalists working in concert with and parallel to one another and the strength of the discipline rests upon their abilities to connect with one another, share information, and challenge their own understanding of the Middle Ages through repeated exposure to the different flavors and facets of the period.

In order to best represent and reflect the multi-faceted nature of the Middle Ages and the diversity of contemporary medievalists, an interdisciplinary approach to understanding the period is in order. The Religion and Pluralism in the Medieval Mediterranean Working Group provides such a space, and it is our intention to keep this momentum going during the 2019-2020 year and beyond. Stay tuned to MI News and Events for details and future meetings!

A. L. Castonguay

Ph.D. Candidate

Department of History

University of Notre Dame