This post contributes to our ongoing special series, “Working in the Archives.” Previously, our bloggers have explained the archival procedures in Morocco and in France. Today, I will discuss some strategies and tips to make a trip to the The Rijksarchief te Gent in Belgium a productive one.

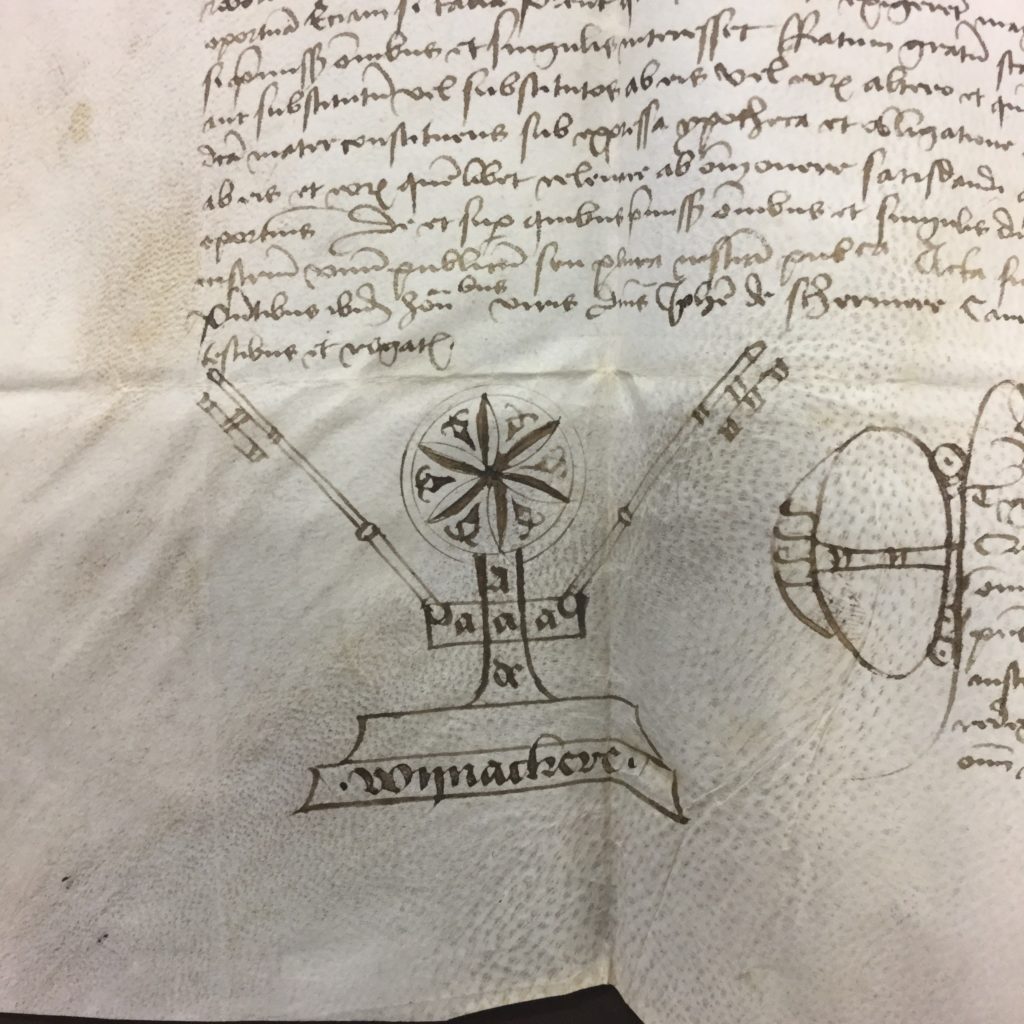

The State Archives in Gent is one of the major depositories of medieval manuscripts in Belgium. I resided and researched in Gent for nine months and hope this blog will help scholars who are traveling to Gent, to the Rijksarchief, to complete research in a short amount of time and with limited knowledge of the city.

Below, I will discuss the practical knowledge needed to make an archive visit productive: how to get to the Rijksarchief from the train station (Station Gent-Sint-Pieters), what is needed to access the archive, how to search for material, how to request that material, and how long the material takes to arrive. Additionally, I will mention some quality of life information- a good place for lunch, for coffee, and for dinner and a drink after a long day in the archive.

How to Get There- Bagattenstraat 43, 9000 Gent

The train to Gent from Brussels Airport (BRU) takes either an hour or an hour and a half, depending on the available trains at the airport when you land. One can take any train going to Brussels Central and switch trains there to arrive faster. Train travel in Brussels is quite easy, with train times and destinations presented in Flemish, French, and English (most of the time, but not always). Upon arriving in Gent-Sint-Pieter’s, there are three easy ways to get to the Rijksarchief- tram, taxi, or by foot. Taking a taxi in Gent is a bit pricey, so if one is on a budget, taking the tram or walking is the better option.

There is a tram that runs regularly from the front of Sint-Pieter’s Station. It is on the Red Line (1) that goes straight into the city center. The stop on the Red Line next to the Rijksarchief is called Verlorenkost. The stop is one street before Bagattenstraat, the street on which the archive is located.

To walk from the train station, one will want to follow the same path as the tram: first, take Konigen Elisabethlaan away from the station; after about a quarter of a mile, bear to the left onto Kortrijkseestenweg; remain on this street through a major intersection. The street changes in name to Kortrijksepoortstraat; continue on this street until you reach Bagattenstraat on the right, and the archive is the third building on the left. It is a large white building.

What You Need to Access the Archive

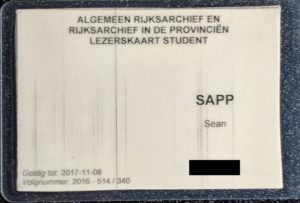

To access the material in the archive, one needs a research card (Lezerskaart). One can spend 5 euros for a weeklong visitor’s research card, or one can spend 20 euros for a yearlong card. You must show your personal reader’s card at every visit. It can be purchased on-site: the annual card gives access to all the reading rooms of the State Archives of Belgium. If one has a student card from the University of Gent, the card is half price.

How to Search For Material

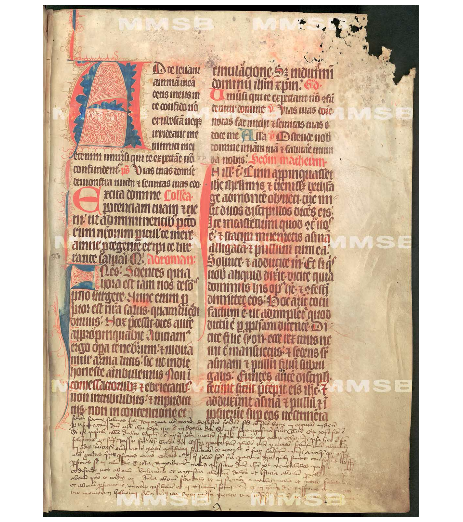

One can search the Rijksarchief online at arch.be/. However, many of the inventories of the collections held in the archive are not online, and can only be consulted in-person. The inventories are shelved on the second floor in the reading room.

To fully understand what the inventories and search tools say, one needs to have some grasp of Dutch. Most of the finding tools are only in Dutch, although one can ask the staff for clarifications and assistance. At minimum, bring a Dutch dictionary, as there is no Wi-Fi at the archive to look up words and phrases online.

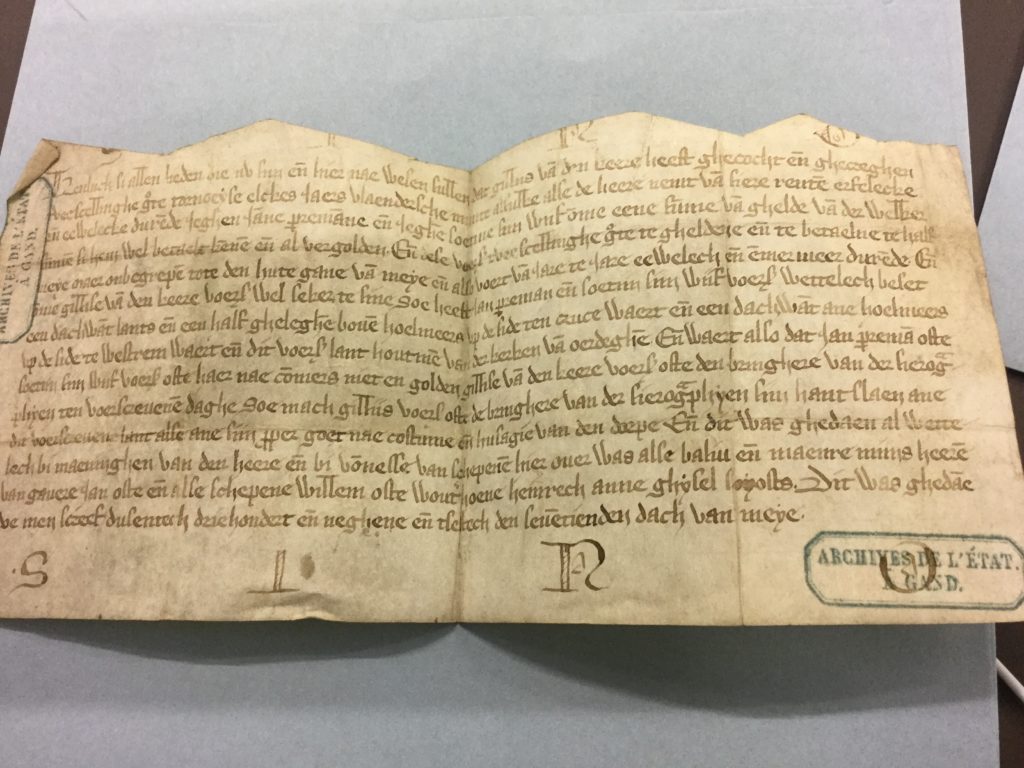

How to Request Material and its Arrival Time

To request a manuscript, one can email the archive a day before to have the material ready in the morning. Otherwise, you must request them in person. The manuscripts are brought to the reading room on the top of every hour, so plan your time accordingly.

Quality of Life

In terms of walkability, Gent is a very manageable city. While it only takes about 15 minutes to walk to the city center from the Rijksarchief, there are nearby cafes and restaurants that are of excellent quality and affordable. My favorite spot near the archive is Vooruit- a restaurant at the other end of Bagattenstraat. It has good food at a good price, with a daily special every day. Vooruit also has excellent coffee. For an afterwork drink or game of pool, turn right out of the archive and go two buildings down to Kaptein Kravate.

Sean Sapp

University of Notre Dame