Having been asked to write the final blog post for the 2018-2019 academic year, I thought I might offer a personal reflection on my own journey as an academic and medievalist, which may, at least in some small way, be indicative of many of the journeys of my friends and colleagues. At a time when the study of the arts and humanities continues to suffer—much to the detriment of democracy at large and despite the fact that these fields enrich our lives and culture—we who work in these areas often find ourselves asking ourselves—and defending to others—why we do what we do. This becomes even more keen when you study older as well as minority languages—and if you’re a medievalist, even though everyone loves the Middle Ages.

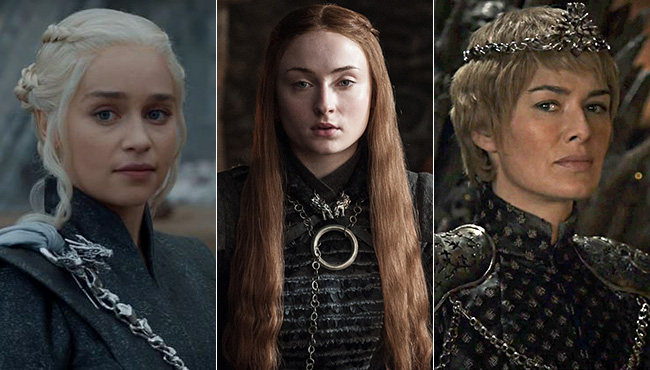

Indeed, it’s been an eventful month for medievalists and for medieval-inspired genres in general. Between Game of Thrones and its issues with portraying women and people of color, the rampant racism medievalists in general are trying to combat, and the usual rush of writing papers for the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, there’s a lot to discuss. As a professor, a researcher, a fandom nerd, a mother, and a procrastinator, I find a lot of this problematic. While I don’t have any solutions, I can at least offer my thoughts on the importance of primary research, especially primary research in its original language, and why being multilingual is important for all of us.

When I was a child, I had two goals: travel to all seven continents and learn exactly why “Y maent yr mynyddoedd y canu, ac y mae’r argwyddes yn dod” meant ‘the mountains are singing, and the lady comes’ in Welsh. Fast forward a few decades, and I’ve achieved five out of seven continents, and I know enough Welsh to recognize that the grammar of “Y maent yr mynyddoedd…” is a little wonky. I’m willing to cut Susan Cooper a little slack, though, because she was the one, through her YA novel The Grey King, that set me on my weird Welsh journey anyway. I was that strange child that wanted to read the Bible in its original Hebrew and Greek form because I knew that it would be the “truest” version (the benefit of being a scholar, I get how problematic that goal is now.) I wanted to speak all the languages and understand all the stories—and I still do!

I grew up in a very white, very middle-class suburb of Los Angeles, where diversity was just a couple of towns over—not that we went there because, you know, traffic and crime rates. Because of this desire to understand beyond my knowledge, as well as the limitations of my own perspective, I show Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “The Danger of a Single Story” TED talk every semester, without fail, no matter what class I’m teaching. I’ve shown it to high school freshmen for Study Skills and upper division college students in a King Arthur class. I’ve seen the video so many times that I can recite parts of it, and it still grabs me every single time.

College was what broke my belief in a single story. A trip to France in high school cemented my hardcore drive to travel EVERYWHERE and see ALL THE THINGS, but college actually pushed me out of the nest and forced me to look multiple perspectives in the face. It dropped a pile of primary sources into my lap and told me to read and digest all of them. While my undergraduate experience didn’t teach me Welsh, it at least pushed me toward the possibility of the Middle Ages, an all-encompassing knowledge of King Arthur, and the idea that I could learn the highly accurate history of it all.

(Oh, my sweet summer child.)

Twenty years later, I am a medievalist with a specialization in the King Arthur of the medieval British Isles and France. I learned Welsh—in Wales no less—to push my ability to analyze primary texts. I used more dead languages than English in my dissertation but still call myself an English major (funny how literature departments are still organized around nation-states). I now teach writing and medieval literature at every college in Buffalo, NY (fine, only three of them, or maybe four…).

I have a six-year-old who can already recite the names of Arthur’s knights as well as tell you what her favorite castle is. She voraciously devours folklore from around the world and prefers Ancient Egypt and stories of Anansi to what mama studies. Her princesses and princes come from India and China and Japan, rather than just the standard Disney European variety. And she’s conquered four out of seven continents. I’m not sure which language(s) she’ll choose when she gets older, but she takes great delight in telling people that gwely means ‘bed’ in Welsh—the apex of my attempt at raising her bilingual and studying Welsh in Wales while pregnant with her. She’s grown up with parchment and chainmail, and she loves swinging around the cloth-and-wood flail she got from a castle in France two years ago. She knows that there is more than one story, and she sees many of those stories every day in her very public, very urban elementary school.

So, why Welsh? Why did a minority language in an English-colonized country become my passion? As a medievalist and Arthurian scholar, it makes sense. Arthur was Welsh. Full stop. Even if I’m not sure I believe he ever existed—since we have little-to-no extant irrefutable historical evidence—I still believe his origins come from Wales, be those the literary origins of the Trioedd Ynys Prydein (Welsh Triads), the “Mabinogion,” or Y Gododdin. If I study Arthurian literature and how the concept of chivalry changed across the English Channel between the ninth and sixteenth centuries, I should know Middle Welsh, as well as Latin, Old French, Anglo-Norman, and Middle English for good measure. Plus, it’s as good an excuse as any to realize that childhood dream of being able to translate a Welsh spell from a kids’ fantasy novel.

Why Welsh? Because there’s a dedicated movement within Wales right now working on reclaiming the heritage that the English took from them, linguistically and culturally. Because there’s a rising demand for Welsh-language schools in Wales, and the number of speakers is actually growing. But also because the ability to read the Triads and other sources of archaic knowledge in their original form ensures that this information will be remembered and kept alive. And because, as the ever-eager scholar, I am always in search of that irrefutable truth for which I longed in my childhood, the Ur-text that explains why the idea of King Arthur still persists in popularity, even when sometimes partnered with giant robots from outer space in modern sci-fi fantasy.

As a medievalist, I know how fragile our material history is. Look at how many erupted into tears as Notre Dame burned last month. Think of how often we wonder about what we lost when the library at Alexandria was demolished or when the Cotton Library burned in the fire of 1731. Think of the destruction of the monasteries under Henry VIII or even of what codices were lost when the Vikings raided again and again in the eighth and ninth centuries. And this still happens—think of the attack on the shrines of Timbuktu in 2012.

The physicality of history is not immortal. While we find new primary sources and discover magical new insights into the past every year with our leaps forward in technology, we still lose so much. Remember when ISIS destroyed the statues at the gates of Nimrud, or when they demolished the Temple of Baalshamin and the Temple of Bel in Palmyra, or, even earlier, when the Taliban blew up the statues of Buddha. Think of every mosque and synagogue that Christians have irrevocably altered in the past thousand years, not the least of which being the Mezquita in Córdoba or the synagogues of Toledo. Our physical artifacts are all we have to help us understand who we were and why things—socially, politically, economically, etc.—are the way they are. Our primary sources, in their original languages, can help us ensure we understand as much as possible about the past, which is the only way we can understand our present moment. Serious study and serious inquiry into the past can help prevent the co-opting of cultural narratives for nefarious purposes, the way white supremacists and the alt-right have pushed for an all-white medieval Europe and erasure of people of color. Why Welsh? Because every language and every culture have something to teach us. Because diversity—in people, in languages, in nature—makes the world richer. Also because I’m obviously a nerd. Why the desire to visit all seven continents? So that I can experience, firsthand, the different stories that each culture, each region, each country presents. So that I can prevent my daughter and my students from recognizing only one story.

Every year for the past three years, I’ve gone into my daughter’s classroom and talked to her classmates about heroes, knights, the evolution of writing, and mummies (because mummies). I’ve given them pieces of parchment to create their own illuminations. I’ve handed them chainmail, leather helms and bracers, and answered how King Arthur died (“It’s complicated…”). It’s not just public scholarship (of which we need more!); it’s also ensuring that these stories, and that consciousness of the materiality of history, are passed on.

Because when I was eleven years old, a friend gave me the Dark is Rising sequence for my birthday, and those books inspired a lifelong love of the Middle Ages and some Welsh warlord named Arthur. Because knowing the political complexities of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s era and being able to read what was said about him in Latin and in Welsh better informs me of why he may have spun Arthur in the imperial/anti-imperial way that he did. Because all we have are fragments to help us understand past cultures, and when we preserve what we have for future generations, we preserve the very diverse voices that white supremacy is trying to kill. This is why I do what I do.

Kara Larson Maloney, Ph.D.

Canisius College