Last week, a small newspaper in Storm Lake, Iowa won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Editorial Writing for the editor, Art Cullen. Cullen’s campaign against agricultural run-off into the Raccoon River was praised as “editorials fuelled by tenacious reporting, impressive expertise and engaging writing that successfully challenged powerful corporate agricultural interests in Iowa.”[1] Unfortunately, last month the judge dismissed the Des Moines Water Works’s legal suit against Sac, Buena Vista, and Calhoun Counties because agricultural drainage doesn’t count as “point source” pollution covered under section 301 of the federal Clean Water Act (1972).[2] The utility has no legal recourse for the damage of nitrate pollution to the drinking water source for 500,000 Iowa residents.

Water is different from most other legally protected resources because of its mobility and mutability. It doesn’t respect political boundaries despite legal statutes; water cannot be separated out from the physical world we inhabit – not even our own bodies. Stacy Alaimo emphasizes the ineluctable character of material agencies, “the often unpredictable and always interconnected actions of environmental systems, toxic substances, and biological bodies,” that cannot be ignored no matter how hard we try to control our environments. Ursula Heise, analyzing systems rather than agentic intra-action, argues that “what is crucial for ecological awareness and environmental ethics is arguably not so much a sense of place as a sense of planet—a sense of how political, economic, technological, social, cultural, and ecological networks shape daily routines.”[3] In other words, the local environment experienced by an individual cannot be separated from the multifarious aspects of global networks, nor can the global be understood without the local experience of limited primary interaction. We need a system that recognizes the physical and social interconnectivity of water as a part of our bodies, our basic rights, our livelihoods, and our common good.

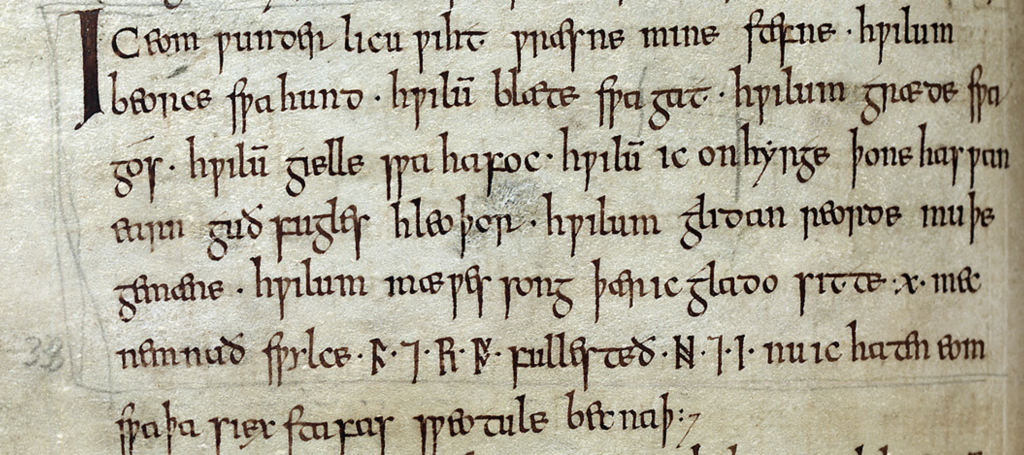

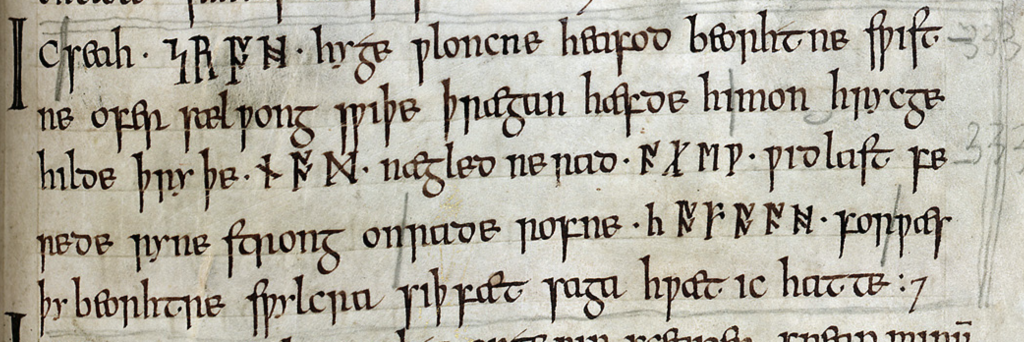

Since our modern legal system is ill-equipped to deal with these challenges, I suggest an alternative model from the medieval period when people were more cognizant of their dependence on nature. Jónsbók represents an integration of the pre-existing Icelandic legal codes – primarily known to us from the Grágás law codes – and the Norwegian law code, Nyere Landslov (1271-74).[4] The Grágás law codes developed from an oral tradition whereby one-third of the legal code was recited each year at the annual Alþingi, or national legislative meeting where legal claims were resolved. The Jónsbók laws were written down in 1117 by unanimous consent (as the story goes) and two early fragmentary copies survive: Konungsbok (Copenhagen, Royal Library, GKS 1157 fol, c. 1260) and Staðarhólsbók (Reykjavik, Árni Magnússon Institute, AM 334 fol, c. 1280). A later manuscript – Reykjavik, Árni Magnússon Institute, AM 351 fol, fol. 1ra-64rb – provides the best manuscript witness since it includes the complete text of Jónsbók along with the 1294, 1305, and 1314 amendments.[5]

The most significant difference between the medieval Icelandic law code and modern U.S. water laws is in the rights and significance given to in-stream use of water, particularly fishing rights. To understand the U.S. system of water law one must first understand the 100th meridian division and how the landscape and precipitation patterns influenced the historical development of the law. Essentially, riparianism in the Eastern states functions through “the sharing of a watercourse by all of the landowners bordering it, regardless of whether a user had ever put water to work previously.”[6] West of the 100th meridian, precipitation is significantly less due in part to the impact of the Rocky Mountains on rainfall patterns.[7] Prior appropriation – qui prior est in tempore potior est in jure as the California Supreme Court wrote in the seminal case Irwin v. Phillips (1855) – holds that whoever is first to use the water has the first right to the water regardless of land ownership. Over time states began to protect certain uses or adapt riparian principles into the prior appropriation system, but although “[a] states constitutions or statutes declared water to public, … nearly all water was appropriated for private gain.”[8] Neither the riparian nor the prior appropriation systems originally included in-stream usage.

Jónsbók VII,56 creates a community obligation when it delineates the process for reclaiming one’s rights when in-stream rights have been compromised. Blocking the stream and passage of fish triggers the community obligation:

Each man may place nets in his part of the stream, but in such a way that the fish are able to swim up into every part of the stream. God’s gifts [i.e., fish] are to go to the mountain as well as to the shore, if they want to go. If, however, a man blocks the stream, then those men who own the stream higher up are to issue a five days’ notice summons from the assembly to the one who blocked the river to come and remove the blockage. If he refuses to move the blockage, then they are to ask for help to remove it. Each householder who refuses to go with him is fined an ounce-unit to the king. Those who illegally blocked the stream are to pay a mark to each man who lives higher up and who lost the right to fish because of the obstruction in the stream.[9]

Unlike earlier passages which limited recompense to the damages done (to land and animals) and a trespassing fee, persons who block the passage of fish in the river are required “to come and remove the blockage” upon notice by the local assembly. If the offender refuses to remove it, the burden passes to the community at large. Jb. VII,56, therefore, creates a community obligation to correct the damage to the free movement of fish within the river, presumably because it affects all the householders in the assembly regardless of whether they utilize their fishing rights. The damages owed are extended not just to the individual who lost the right to fish but to the king and to “each man who lives higher up” due to the obstruction. In this way, community obligation for the shared right for in-stream supersedes the diversion or obstruction needs of individual users while explicitly recognizing the necessity of river passage for fish populations. The fishing rights section of Jónsbók makes clear that while primary water rights conflict occurs at the immediate interpersonal level, the ripples of such actions impact other riparian owners, local householders, district assemblies, and the super-national treasury, as well as impacting the ability of fish populations to survive human intervention.

Medieval Icelandic code of water rights represents a more ethical and holistic perspective on water rights. Jónsbók-style limitations on water removals and blockages that impede fish migration and movement might have served as a restraining force on the proliferation of dams, water treatment facilities, and industrial waste discharge on the waters of the U.S. by requiring proponents to more thoroughly take into consideration not just other human users, but also the impact on nonhuman organisms, i.e. the flora and fauna that developed within and alongside the riparian biomes.[10] While the Clean Water Act (1972) has attempted to redress the problem of longterm environmental damage due to human actions, it is fighting an uphill battle against long-established rights where individual (mostly corporate) extraction rights are privileged over in-stream usage, the local community’s needs, the larger public good, and environmental concerns. We would be better served by a legal code that recognizes the intersections of needs and rights and Jónsbók provides us with a foundation to build on.[11]

Mae Kilker

University of Notre Dame

[1] Staff & Agencies, “Tiny, Family-Run Iowa Newspaper Wins Pulitzer for Taking on Agriculture Companies,” The Guardian, April 10, 2017, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/apr/11/tiny-family-run-iowa-newspaper-wins-pulitzer-for-taking-on-agriculture-companies.

[2] Donnelle Eller, “With Water Works’ Lawsuit Dismissed, Water Quality Is the Legislature’s Problem,” Des Moines Register, sec. Money, accessed April 15, 2017, http://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/money/agriculture/2017/03/17/judge-dismisses-water-works-nitrates-lawsuit/99327928/.

[3] Ursula Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008), 55.

[4] Jana K. Schulman, Jónsbók: The Laws of Later Iceland, (Saarbrücken, Germany: AQ-Verlag, 2010), xv.

[5] Schulman, Jónsbók, xxii-xxiii. The amendments, in manuscript order, are King Erikr’s Amendments (1294/1295), King Hakon’s Amendments (1305), King Hakon’s Amendments (1314), and King Hakon’s Amendments (1308), which latter pertain only to Norwegian law. It excludes only three sections: royal women’s inheritance, the earl’s oath, and the presiding judge’s oath. Schulman terms the three omitted sections “unnecessary” in the new legal context of the late 14th century.

[6] “A Universal Sense of Necessity and Propriety” in History of Water Rights, n.p.

[7] Excluding, of course, portions of the Pacific Northwest where the biome is a temperate rainforest.

[8] “A Universal Sense of Necessity and Propriety” in History of Water Rights, n.p.

[9] Schulman, Jónsbók, VII.56 (263).

[10] For more on the co-evolution of human culture and nonhuman species within specific geophysical boundaries, see Wendy Wheeler, “‘Tongues I’ll Hang on Every Tree’: Biosemiotics and the Book of Nature,” in Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment, ed. Louise Westling. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014, 121-35.

[11] I’ll be presenting more on water law issues and the approach codified in Jónsbók at the ASLE biennial conference in Detroit (June 20-24).