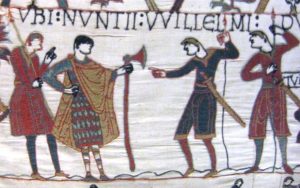

Vikings are a very hot topic right now; there’s no question. Within the thriving genre of medievalism, Vikings have recently proven an especially sexy and profitable subject for contemporary pseudo-historical fiction, particularly in television series like the History Channel’s Vikings (2013) and Netflix’s The Last Kingdom (2015). Both these series are fundamentally anachronistic and closer in many ways to medieval fantasy than an accurate historical representation of the early medieval period known as the Viking Age (793–1066 CE). Inaccuracies are, of course, not unique to medievalism involving Vikings, and historical liberties are more abundant in historical fiction set in ancient and medieval times.

Still, these television shows are very popular and therefore highly influential. Even the anachronisms and inaccuracies in popular medievalism provide effective conversation starters when teaching the subject by offering both a hook into the material and a chance to separate fact from fiction. But, in today’s world by far the most important reason for medievalists to know the trends in popular medievalism and engage with this media directly is white nationalism. As scholars of the period, we must be aware of information, misinformation and disinformation that is being widely disseminated if we are to have any hope of using our voices to help debunk, nuance and contextualize shows like Vikings and The Last Kingdom with a watchful eye toward white supremacist interpretations and appropriations.

Many medievalists of color have sounded the alarm—again and again—warning that this monster lurked in the shadows. Over five years ago, Sierra Lomuto stressed how “When white nationalists turn to the Middle Ages to find a heritage for whiteness—to seek validation for their claims of white supremacy—and they do not find resistance from the scholars of that past; when this quest is celebrated and given space within our academic community, our complacency becomes complicity” (2016).

In the wake of the riotous “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017, where some alt-right protesters donned crusader and Viking garb, scholars such as Dorothy Kim, Mary Rambaran-Olm and others have repeatedly warned the field of the dangerous appropriations of the medieval by white supremacists. Immediately following Charlottesville, Kim insightfully cautioned her fellow medievalists that “The medieval western European Christian past is being weaponized by white supremacist/white nationalist/KKK/nazi extremist groups who also frequently happen to be college students” (2017). More recently, Rambaran-Olm has pointed out that “far-right identitarian groups [are] seeking to prove their superior ancestry by portraying the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ in ways that both promote English identity and national sociopolitical progress” (2019).

Moreover, alt-right activists have postured as pseudo-medievalists in order to further these white supremacist narratives and misappropriations of the Middle Ages. For example, Milo Yiannopoulos is known for his ad hominem editorial “The Middle Rages” that targets numerous medievalists of color. Still somehow, the “jousting” between medievalists of color and the alt-right was not enough to shake many white medievalists into action, despite the very real threat posed by white supremacist weaponization of the medieval.

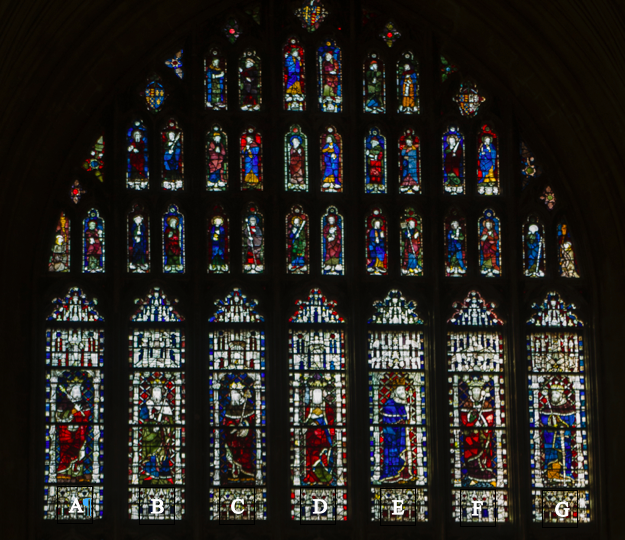

Since the Nazi appropriation and sacralization of the “Germanic” in the service of white supremacy, medieval literature—especially Scandinavian myth and legend—has been rhetorically mobilized as an imagined “pure white” era in Northern Europe prior to encountering and intermingling with nonwhite peoples, despite clear historical evidence of multi-cultural trade interactions between ancient and medieval peoples. This ideology has infiltrated the neopagan religion known as “Odinism,” which varies widely and spans the political spectrum, but harbors a perverse, neo-Nazi strain (sometimes called Wotansvolk meaning “Odin’s Folk”) that has long haunted the movement.

Odinism—named for the chief Scandinavian god of war, Odin—refers to modern New Age interpretations of indigenous religion in pre-Christian Scandinavian, and The Southern Poverty Law Center reported that “A neo-Pagan religion drawing on images of fiercely proud, boar-hunting Norsemen and their white-skinned Aryan womenfolk is increasingly taking root among Skinheads, neo-Nazis and other white supremacists across the nation” more than twenty years ago. More recently, “Anglo-Saxon” neopaganism, sometimes called “Heathenry” to further ground their practice in the language of the culture they idolize, has grown and frequently provides a haven for white supremacist rhetoric.

The alt-right has mobilized medievalism toward nefarious ends, fashioning harmful narratives of white supremacy, which have been rhetorically weaponized by domestic terrorists such as the “Q Shaman” also known as Jake Angeli, but whose real name is Jacob Anthony Chansley. As a QAnon promoter and influencer, Chansley is described as a pseudo-celebrity at alt-right rallies, flashing his tattoos, including three prominent Norse symbols: Thor’s Hammer [Mjǫllnir], the Valknut and the World Tree [Yggdrasil]. All three were proudly displayed as he sat in Vice President Mike Pence‘s seat in the Senate, after the Pence was forced to retreat from the angry mob calling for his head.

Moreover, Chansley’s horned helmet (while almost certainly referencing other traditions as well) represents a continuation of the Victorian anachronistic introduction of horned helms on Vikings and Valkyries, drawn from classical depictions of Roman Victories. Chansley’s flag-spear may be intended as a reference to Odin’s spear, Gungnir, which further points to white nationalist medievalism. In the case of his horned helmet, Chansley’s ignorance is on full display, as his caricature more closely resembles the ahistorical symbol of the Minnesota Vikings’ football team than anything remotely resembling what a medieval Viking might have looked like. Chansley joined with other pro-Trump supporters to form a violent mob which stormed the United States Capitol on January 6th, 2021.

Of course, it must be emphasized that this insurrection was perpetrated specifically by a pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” MAGA mob, there in support of the president’s blatantly false and dangerous claims that there was election-altering voter fraud during the recent 2020 presidential election (which he soundly lost to Democratic rival Joe Biden). This mob, incited by the president, sought to disrupt the lawful process outlined in the US Constitution by any means necessary in order to overturn a free and fair election.

Donald Trump’s boasting, belligerence and greed does link him with warrior ethics which sustain predatory economies and the Viking activities of marauding, feuding and plundering. The ironic Twitter account, “Beowulf Trump” (discontinued after Trump’s election in 2016), highlights this rhetorical connection by comparing the president’s macho posturing and self-aggrandizing campaign promises to hyperbolic boasts and egoistic attitudes in Beowulf. There were indeed marauders in the Capitol Building on January 6th, and alongside Trump’s red hats, outfitted in army camouflage and waving Trump or Confederate flags, were alt-right Viking wannabes.

This week, the academy has been quick to respond. Alfred Thomas compared the storming of the US Capitol Building to the Peasants Revolt of 1381, although Miriam Müller has disputed this analogy, prompting Thomas to further clarify his argument. Ken Mondschein considered Rudy Giuliani’s terrifying invocation of “trial by combat” in order to spur the MAGA mob into action, and Giuliani later likened his use of the phrase to its function in HBO’s Game of Thrones (2011), which he inaccurately described as “that very famous documentary about fictitious medieval England.” Matthew Gabriele reflected on the role of medievalism in the seditious attack at the Capitol Building, pointing out that like at Charlottesville, in addition to Viking-oriented medievalism, rioters also sported crusader symbolism to signal their white nationalism. Helen Young responded to the incident by offering an explanation of why white supremacists often embrace medieval symbolism, noting that “the association of European Middle Ages and white identities reflect modern racism more than medieval realities.” She emphasizes that “Medievalist symbols have been linked to white European identities for centuries. Their use by violent extremists mean that this connection can not be denied, ignored or thought of as a neutral choice.”

On January 13th, the Medieval Academy of America issued a direct response to the insurrection acknowledging the “presence of pseudo-medieval symbols and costumes among the rioters in the Capitol” and recognizing “our discipline’s complicity in the racist narratives of the past, and our responsibility to advocate unequivocally for anti-racism both in our policies as an organization, and in our teaching and scholarship as individuals.” More white medievalists need to be willing to stare this beast in the face and recognize that it is our problem too. It is my view that we should not idly concede medieval studies to the likes of white supremacists. We must respond. Failing to do so—for far too long—makes us complicit. We need to actively reject white supremacy. We must correct and denounce the alt-right’s misappropriations of the medieval both publicly and in the classroom by identifying these dangerous narratives as white nationalist propaganda.

If what we all witnessed last week is any indication of the widespread public ignorance we as scholars are up against, we surely have our work cut out for us. As medievalists, we must heed well the warnings of our colleagues of color and more forcefully and ubiquitously address the problematic phenomenon of white nationalist weaponizing of the medieval. Let me add my voice to those within the academy who are calling attention to this dire issue: the recent use of medieval symbolism during the insurrection at the US Capital is but the latest in a horrific trend that cannot be ignored in the field and must be loudly condemned as nonfactual and nonsensical white supremacist rhetoric in the guise of medievalism.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading

Baker, Peter. “Anglo-Saxon Studies After Charlottesville: Reflections of a University of Virginia Professor.” Medievalists of Color (2018).

Barnes, Sophia. “Capitol Rioter Seen in Horned Hat, Carrying Spear Arrested: US Attorney.” 4 Washington (2021).

Chazan, Robert. “The Arc of Jewish Life in the Middle Ages.” The Public Medievalist (2017).

Cole, Richard. “Make Ásgarðr Great Again!” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2017).

Connelly, Eileen AJ. “Jake Angeli, Capitol rioter in horned helmet, arrested by Feds.” New York Post (2021)

Dockray-Miller, Mary. “Old English Has a Serious Image Problem.” JSTOR Daily (2017).

Elliott, Andrew B.R. “A Vile Love Affair: Right Wing Nationalism and the Middle Ages.” The Public Medievalist (2017).

Elliott, Josh K. “Horn-helmed QAnon rioter among far-right ‘stars’ in U.S. Capitol attack.” Global News (2021).

Fahey, Richard. “Internet Trolls: Monsters Haunting the World Wide Web.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2020).

—. “Mearcstapan: Monsters Across the Border.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2018).

—. “Monstrous Ethiopians? Racial Attitudes and Exoticism in the Old English ‘Wonders of the East’.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2017).

—. “Woden and Oðinn: Mythic Figures of the North” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2015).

Franke, Daniel. “Medievalism, White Supremacy, and the Historian’s Craft: A Response.” Perspectives on History (2017).

Gabriele, Matthew. “Vikings, Crusaders, Confederates: Misunderstood Historical Imagery at the January 6 Capitol Insurrection.” Perspectives on History (2021).

—, and Mary Rambaran-Olm. “The Middle Ages Have Been Misused by the Far Right. Here’s Why It’s So Important to Get Medieval History Right.” Time (2019).

—. “Islamophobes want to recreate the Crusades. But they don’t understand them at all.” The Washington Post (2017).

Goodman, Lawrence. “Jousting With the Alt-Right.” Brandeis Magazine (2019).

Greenspan, Rachel E., and Haven Orecchio-Egresitz. “A well-known QAnon influencer dubbed the ‘Q Shaman’ has been arrested after playing a highly visible role in the Capitol siege.” Business Insider (2021).

Heng, Geraldine. “Why the Hate? The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, and Race, Racism, and Premodern Critical Race Studies Today.” In the Middle (2020).

—. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Höfig, Verena. “Vinland and white nationalism.” In From Iceland to the Americas: Vinland and historical imagination, ed. Tim William Machan and Jón Karl Helgason. Manchester University Press, 2020.

Hsy, Jonathan. “Antiracist Medievalisms: Lessons from Chinese Exclusion.” In the Middle (2018).

Kim, Dorothy. “The Question of Race in Beowulf.” JSTOR Daily (2019).

—. “White Supremacists have Weaponized an Imaginary Viking Past. It’s Time to Reclaim the Real History.” Time (2019).

—. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In the Middle (2017).

—. “The Unbearable Whiteness of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Knight, Ellen. “The Capitol Riot and the Crusades: Why the Far Right Is Obsessed With Medieval History.” Teen Vogue (2021).

Lee, ArLuther. “Protester in Viking headdress ID’d as Trump supporter, not Antifa.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (2021).

Little, Becky. “How Hate Groups are Hijacking Medieval Symbols While Ignoring the Facts Behind Them.” History.com (2018).

Livingstone, Josephine. “Racism, Medievalism, and the White Supremacists of Charlottesville.” The New Republic (2017)

Lomuto, Sierra. “Public Medievalism and the Rigor of Anti-Racist Critique.” In the Middle (2019).

—. “White Nationalism and the Ethics of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Luginbill, Sarah. “White Supremacy and Medieval History: A Brief Overview.” Erstwile: A History Blog (2020).

Mas, Liselotte. “Auschwitz, QAnon, Viking tattoos: the white supremacist symbols sported by rioters who stormed the Capitol.” The Observers (2021).

Mills, Ryan. “The ‘Q Shaman’ on Why He Stormed the Capitol Dressed as a Viking.” National Review (2021).

Mondschein, Kenneth. “Trial by Combat: Medieval and Modern.”Medievalist.net (2021).

Müller, Miriam. “Revolting Peasants, Neo-Nazis, and their Commentators.” Medievally Speaking (2021).

Narayanan, Tirumular. “Frazetta’s “Death Dealer” and the Question of White Nationalist Iconography at Fort Hood.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2020).

Olusoga, David. “Black people have had a presence in our history for centuries. Get over it.” The Guardian (2017).

Perry, David. “How to Fight 8chan Medievalism – and Why We Must.” Pacific Standard. (2019).

—. “What to Do When Nazis are Obsessed with Your Field.” Pacific Standard. September 6, 2017.

—. “White supremacists love Vikings. But they’ve got history all wrong.” The Washington Post. (2017).

Rambaran-Olm, Mary. “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting “Anglo-Saxon” Studies.” History Workshop (2019).

—. “Anglo-Saxon Studies [Early English Studies], Academia and White Supremacy.” Medium (2018).

Reed, Sam. “Here’s the Story Behind Those Viking Helmets at the Capitol.” In Style (2021).

Romey, Kristin. “Decoding the hate symbols seen at the Capitol insurrection.” National Geographic (2021).

Schuessler, Jennifer. “Medieval Scholars Joust With White Nationalists. And One Another.” The New York Times (2019).

Steinbuch, Yaron. “Shirtless man in horned helmet at Capitol protest identified as QAnon backer.” New York Post (2021).

Sturtevant, Paul B. “Leaving “Medieval” Charlottesville.” The Public Medievalist (2017).

Symes, Carol. “Medievalism, White Supremacy, and the Historian’s Craft.” Perspectives on History (2017).

Thomas, Alfred. “1381, 2021, And All That.” Medievally Speaking (2021).

—. “Politics in a Time of Pandemic: The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 and the Storming of the Capitol by Trump Supporters in Historical Perspective.” Medievally Speaking (2021).

Vinje, Judith Gabriel. “Viking symbols “stolen” by racists.” The Norwegian American (2017).

Whitaker, Cord J. “Game of Thrones’ Peasants are a Problem of White Supremacy – and It’s Victims, too.” In the Middle (2019).

Young, Helen. “Why the far-right and white supremecists have embraced the Middle Ages and their symbols.” The Conversation (2021).

—. “White Supremacists love the Middle Ages.” In the Middle (2017).

—. “Re-making The Real Middle Ages (TM).” In the Middle (2014).