The Central authorities, of course, expect the people of Hong Kong to be loyal Chinese patriots. And the Hong Kong population may indeed have a certain identification with the wider Chinese heritage and a pride in being part of that heritage. This does not automatically translate into an attraction to the People’s Republic.

During the first century under colonial rule, Hong Kong was a free port involved in entrepot trade. Most residents (aside from the farmers in the rural areas in the New Territories) were “sojourners”: they were in Hong Kong to engage in business, but still rooted in their old home towns on the mainland and intending to return home upon retirement or when the business was done. This changed with the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949. The colony saw an influx of people who, for one reason or another, did not want to live under communism. Especially after the “socialist transformation” there was a massive influx of capital (and capitalists) from Shanghai, China’s previous financial center, with Hong Kong taking over much of Shanghai’s earlier role. Hong Kong grew from a sleepy seaport to a major industrial and financial power. There was further immigration to Hong Kong in the late 1950s, when the Great Leap Forward degenerated into a massive famine; and another growth spurt in the late 1960s, as it took in the effluence of the Cultural Revolution.

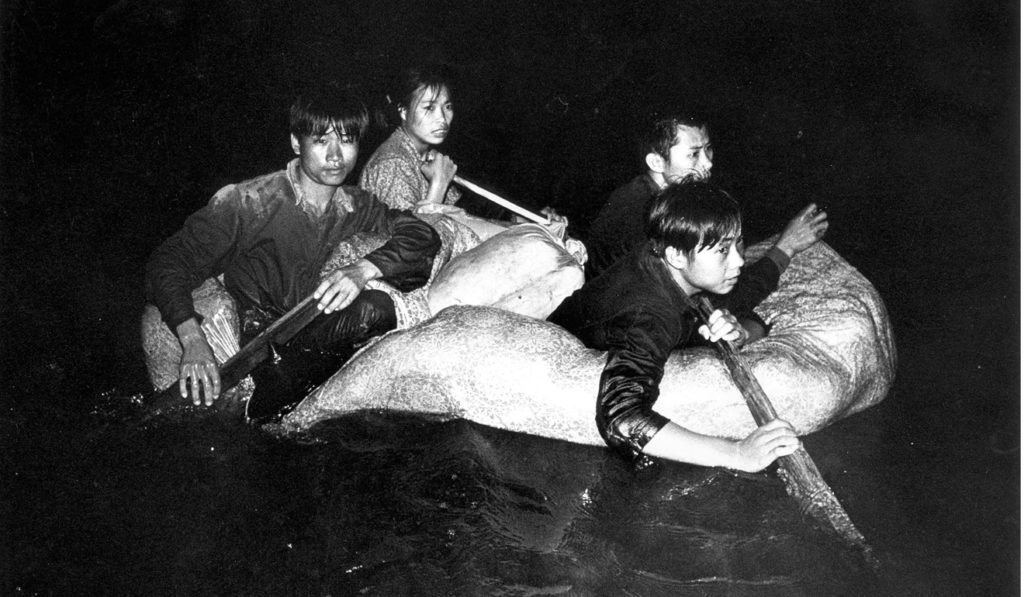

During this time there was continued interaction between Hong Kong and the mainland. While China’s new rulers, like all of the old ones, denied the legitimacy and validity of the treaties ceding Hong Kong, they tolerated the colony as their main source of foreign currency: farmers from the nearby areas of the mainland would sell their produce in Hong Kong, and deposit Hong Kong dollars—hard currency—into banks inside China proper. But movement back and forth across the border was more restricted than before; and, indeed, by the late 1960s the Hong Kong authorities were taking active measures to prevent further immigration.

(South China Morning Post)

The upshot was that the great mass of people living in Hong Kong were there because they did not want to live in mainland China. The generations growing up after 1949 increasingly lost a sense of identity with their ancestral roots on the mainland. They considered themselves to be Hong Kongers, Chinese to be sure but not the same as the mainland Chinese.

If there was little sense of loyalty to “China” (or at least to the People’s Republic), would that imply instead a loyalty to Britain? Maybe loyalty might be too much to ask. Certainly, under Elizabeth there was no real democratic participation: the Governor was appointed by the Crown, advised by an oligarchical Legislative Council—advised, since it did not have actual legislative authority—and the colony governed by a combination of the Colonial Office in London, a locally recruited civil service, and wealthy local businessmen. But the ordinary person also enjoyed an almost full panoply of civil liberties under a regime that allowed him to live pretty much as he chose. Lack of democracy was the price paid for not having to live in China.