Chapter Overview:

In this chapter, Roberts addresses the unique physiology of the human shoulder and hands and how they reflect our evolutionary past. She also talks about the things we share with other apes as well as what sets us apart and why these differences may have arisen.

Chapter Summary:

Human arms and hands are much more mobile than those of most other mammals. Our shoulder anatomy is owed in part to our climbing ancestors. We have free-floating scapulae and very mobile arms. Shoulders are a very mobile and as a result of this mobility, they dislocate more easily than more stable joints. Human forearms are also very mobile. They have the ability to pronate which allows rotation around the arm-hand axis. Other apes have more upward facing shoulders because of their use for climbing. Roberts discusses possible reasons that our shoulders have rotated downwards. Perhaps they conferred an advantage for long distance running. Some suggest that the change in shoulders may be because of advantages for throwing. This seems to have been very important because much of our anatomy seems well suited for throwing. There is little fossil evidence of throwing before the invention of tools specifically designed as projectile weapons such as throwing spears. There is conclusive evidence that throwing was used for hunting by 300,000 years ago.

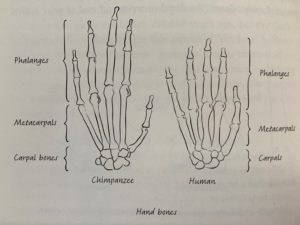

Next, Roberts discusses the ability of human and ape wrists to be in both supinated and pronated positions allowing us to use our hands for even more things. Our hand bones are different than those of chimps in very significant ways. They have short thumbs and long phalanges compared to our more modest phalanges and large, strong thumbs. Chimpanzees use their fingers to grip sticks while humans use their thumbs to allow for greater control and precision. Humans use their hands with a combined precision and strength grip that allows us greater dexterity with our hands.

Ardi’s fossils are useful for determining when hands diverged between humans and other apes. Longer fingers are associated with grasping tree branches to hang from. Evidence suggests that metacarpals have elongated in apes while they have shortened in humans since our last common ancestor. Curved finger bones in Lucy and her species suggest that they spent some time in trees, as well as walking bipedally. Her spine suggests that this amount of time was not great because it is very flexible and much better adapted to walking than climbing where she may risk injury. By Homo habilis hands were more similar to modern humans, though more robust than modern humans.

We also have different musculature in our hands than other primates. There are three muscles that are unique to the human hand and all of them flex the thumb in different ways, underlying our unique use of our thumb for precision and strength gripping. Some suggest that these muscles are a result of toolmaking. This is true for the robust thumbs we see in earlier hominins too, which may have been good for the high impact methods used to create tools. Another theory suggests that our robust thumbs are a result of pressures experienced when using stone tools instead of when they were being made.