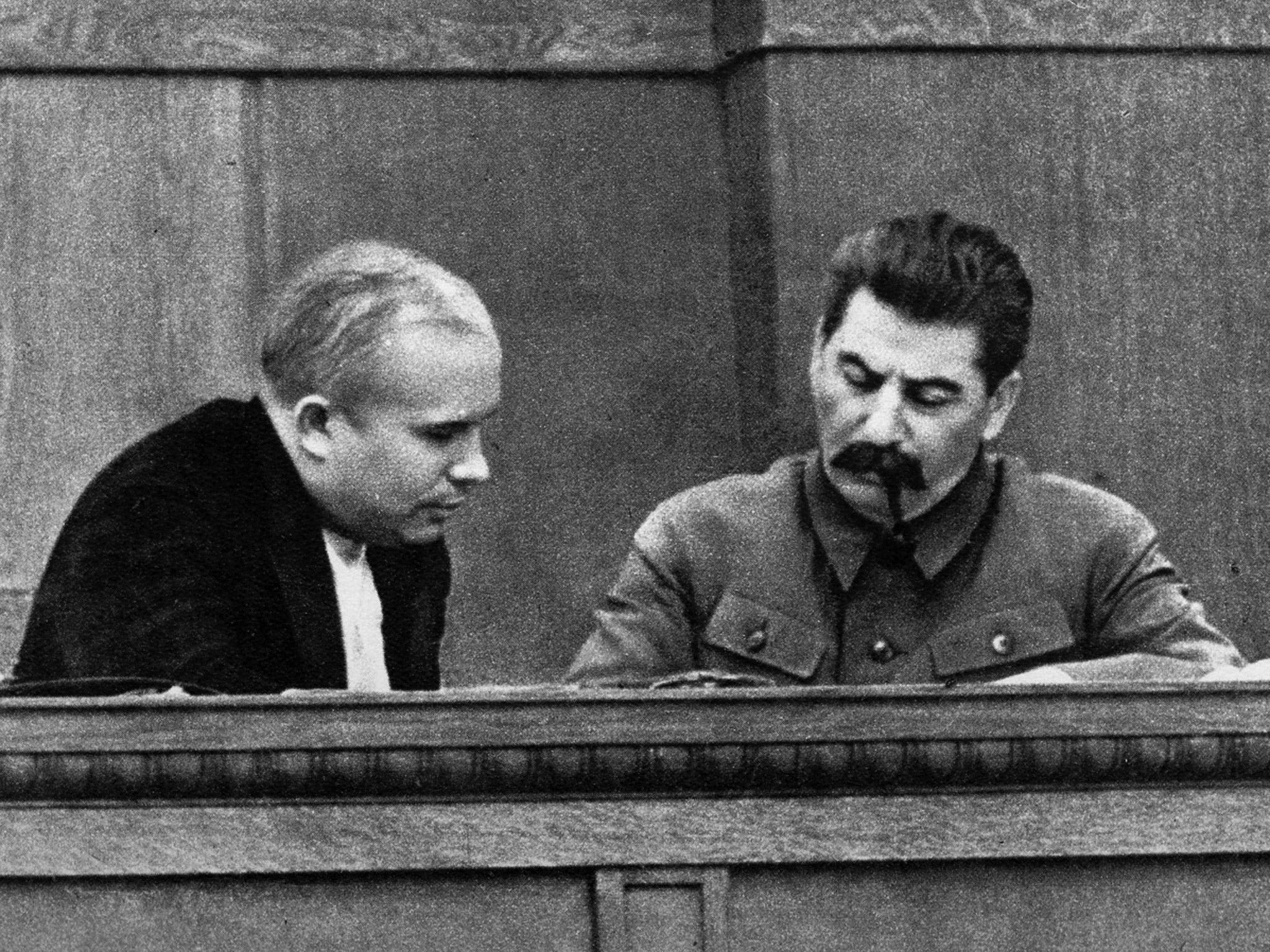

As Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev stood on the podium, a hush fell over the room. It was 25 February 1956 – 60 years ago to the day – and the country’s highest-ranking Communist party members had assembled at the 20th Congress, a closed session that would be the last convened at the party’s headquarters in Moscow. When Khrushchev, Josef Stalin’s immediate successor, began to talk, some among the crowd erupted into shrieks, others collapsed and were carried out by friends. Everybody was in a state of shock.

For the next four hours, Khrushchev did what no other Soviet politician had dared in the decades before, launching a ferocious attack on Stalin’s reign of “brutal violence” and “cruel repression” since coming into power in 1922.

In what became known as “the secret speech”, Khrushchev denounced his predecessor, who had died of a brain haemorrhage three years before, as “despotic and capricious” and lambasted the system of violence that stemmed from Stalin’s invention of the “enemy of the people”. It was the greatest blow ever to have been delivered to Stalin’s world of cruelty and paranoia, which for decades had battered the lives of ordinary Soviet citizens. Millions of people had been shot or sent to labour camps, accused of harbouring anti-Soviet feelings. A society whose state apparatus thrived on accusations of sabotage and counter-revolution had been called into question.

Within hours, Khrushchev’s words were speeding towards Europe and the United States. The CIA was allocated $1 million from the US government to obtain a copy, and the State Department published it in full within weeks. The contents were met with delight abroad as world leaders finally saw the sign they had been waiting for: the walls of Stalin’s terror had finally started to crumble.

But the speech was left out of the Soviet Union’s official narrative for years. Circulating the Eastern bloc in samizdat for three decades, it wasn’t until 1989 that it was finally published in full in the Soviet Union.

The effects of Khrushchev’s words were almost immediate: monuments to Stalin across the country were torn down and thousands of political prisoners were released. But the limits of Khrushchev’s thaw soon became clear. He continued to preside over political persecution and the represseion of religion, and protected Communist Hungary by sending Soviet forces to crush a revolt.

Khrushchev condemned the world Stalin had created, but he never fully broke from it. It was the beginning of what was to become a difficult path to understanding Stalin’s legacy. Even now, 60 years after those damning words, Russia has failed to fully reckon with the atrocities committed.

“Some people say it’s demoralising to remember and talk about the horrors of the past,” says Roman Romanov, director of a new, state-funded Gulag Museum in Moscow. “Some people say that it’s better to forget – or that it was only criminals who were sent to the camps, so why memorialise them? We have to find a language with which to communicate about these things again, even if it’s difficult.”

The museum, which describes the system of gulags and political repression under Stalin using artefacts and video testimonies from gulag survivors, is fully funded by the state. Vladimir Putin has also authorised a new monument to victims of political repression to be unveiled later this year. Yet the perception of Stalin as an “effective manager” has significantly risen under Putin, while Stalin-era rhetoric has returned. Opposition figures are increasingly branded “enemies of the state” again and non-governmental organisations labelled “foreign agents”.

And while critics accuse Putin of presiding over the creeping rehabilitation of Stalin – preferring to downplay the human cost of his rule to focus on the Soviet Union’s successes – an independent poll conducted in Russia in March last year revealed that 45 per cent of those questioned said they thought that the sacrifices made under Stalin were justified given the speed of the Soviet Union’s economic growth during his rule. It’s a statistic that has nearly doubled since the same poll was taken two years before.

Stalin may have been a leader whose tenure saw many dark moments, but they were ultimately overshadowed by his greatest success, guiding the Soviet Union to victory in the Second World War – or so the story goes. And it’s a narrative that takes on profound resonance in Russia today. Putin’s efforts to make Russia a resurgent superpower call on grand images of the country’s past: great, internationally feared, and militarily capable of winning wars. Be prepared, the narrative warns, Russia’s greatness comes at a price.

“There are groups of people, most of whom grew up and were educated in the years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, who have a kind of nostalgia for the USSR, who think life before its collapse was better than today,” says Romanov. “For them, Stalin is tied up with that, so his rehabilitation becomes part of an effort to restore the ‘great Soviet past’.

In January this year, a new cultural centre celebrating Stalin was unveiled in the Tver region near Moscow. Local communists declared 2016 to be the Year of Stalin throughout the region. Alongside this, new staff at Perm-36, a former gulag that was turned into a museum in the Urals, have come under fire for softening the image of Communist-era repression after pressure from the regional administration.

Alexander Drakler, a history teacher at a Moscow school, says that downplaying the bleaker aspects of Stalin’s rule has seeped into education. “There is pitifully little on so many of the dark periods of Soviet life under Stalin. The deportation of the Chechens, for example, [when in 1941 Stalin forcibly expelled nearly half-a-million Chechens to Central Asia, with thousands dying along the way], has only one or two paragraphs devoted to it in history textbooks for kids. Why is something so important given such little attention?”

Stalin’s rehabilitation in Russia comes amid Putin’s shift towards authoritarianism. Some of the Soviet Union’s darkest practices have made an ominous return: curtailing freedoms and consolidating his power, Putin has created a modern Russia in which dissent once againcarries a high price.

Eyewitness: ‘For two weeks they didn’t let me sleep… they kept trying to get me to confess to crimes’

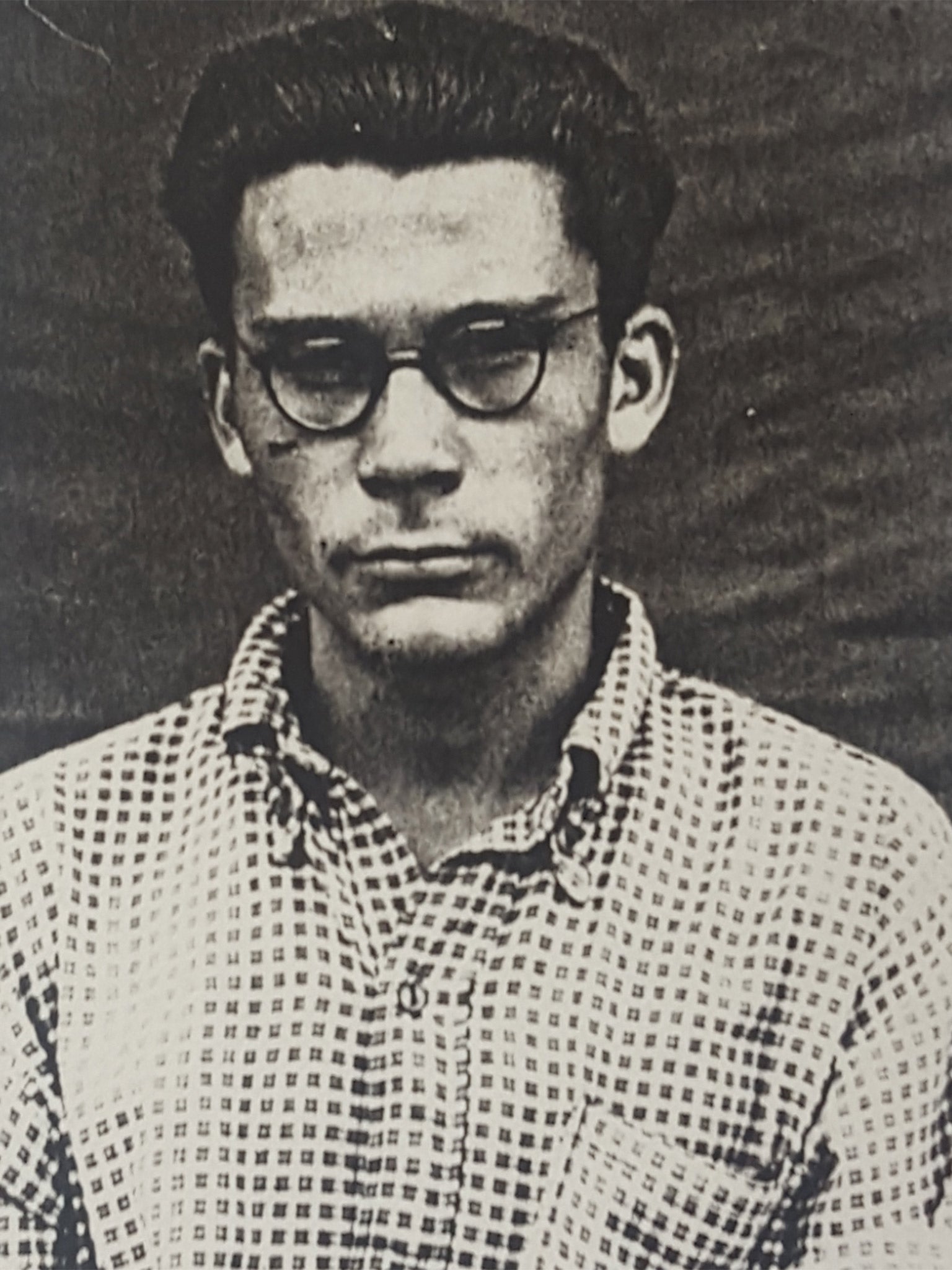

It was a cold January day in 1951 when Yury Naydenov-Ivanov, a factory technician, was sitting with his friends in a café on Moscow’s central street, Old Arbat. The trio had ordered drinks when a stranger sat down in the empty chair next to them. The men stiffened. Terrifying tales of arrests and disappearances that had circulated the Soviet Union for years often began with the presence of a stranger.

“We need to ask you some questions,” the man said quietly. The man was a member of Josef Stalin’s dreaded secret police, the NKVD. Seemingly out of nowhere, more men entered the café, took Yury and his two friends by the arms and bundled them into a van. The next time Yury saw light, it was reflected from the bright ceiling of a cell in the NKVD’s headquarters in Lubyanka Square, and in front of him were his interrogators.

The nature of the events that led to their seizure were by no means exceptional. Zhenya Petrov, one of the three men at the café, had purchased a copy of a magazine called America, a Russian-language illustrated monthly, chronicling life in the United States. Inspired by its content, Zhenya telephoned the magazine’s office in Moscow with a question: what is life like for Russians in America? The magazine wasn’t illegal. It circulated with permission from the Soviet authorities even then, despite a deep-rooted paranoia that viewed anything foreign as a threat to Soviet values. But the question Zhenya asked proved his undoing. “They tapped his phone and heard the whole thing,” Yury recalls. “They were waiting for him that day.”

The journalist Zhenya had spoken to on the phone invited him to come down to his office in the city centre; Yury and another friend agreed to come along, too, all three meeting first at the café. Zhenya was the target for arrest. Yury was collateral damage. “For two weeks they didn’t let me sleep,” Yury says. “That was worse than being beaten. My interrogators kept trying to get me to confess to crimes I hadn’t committed. Each time that I’d nearly fall asleep, they’d wake me up and start it all over again.”

After a fortnight’s interrogation and four months sitting in the NKVD’s jail, Yury was accused of “anti-Soviet propaganda” and attempting to flee the country, sentenced to 10 years of labour and sent to a camp near the border with Kazakhstan. He was 20 years old.

Yury was one of around 40 million people who passed through the Soviet Union’s gulags after they first appeared in 1918. An abbreviation for Chief Administration of Corrective Labour Camps, the gulags were a vast network of forced labour camps that symbolised the cruelty of Stalinism. Described by writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn as “a chain of islands”, the gulags became the graveyard for millions of Soviet citizens who were accused of harbouring “anti-state” thoughts. “Every day we were woken up at 5am and worked on constructing the colony,” Yury recalls. “The summers could get really hot – which made the building work we had to do uncomfortable – but winters were worse.” Still, he could be called one of the lucky ones. “Being near the border [with Kazakhstan],” he continues, “we didn’t have it as bad as those near the Arctic, for example.” These unfortunates included Zhenya, who worked for two years in northern Russia before he perished.

Yury’s imprisonment should have ended sooner than it did. Although Stalin died in 1953, thus starting the staggered release of most gulag prisoners, it wasn’t until 1955 – two years after sentencing – that he was freed. “None of us even knew that Stalin had died!” he says. “We kept working as normal because nobody said anything to us. I couldn’t believe it. We used to say that SSSR [USSR] stood for ‘Smert Stalina Spaset Rossiu’ [The Death of Stalin Saved Russia].”

But his ordeal didn’t end there: “We were freed, yes, but we were amnestied, not rehabilitated. The state pardoned me for political misdeeds I’d never committed, and that was it. It was written in all my documents, which meant, as soon as prospective employers saw my documents, that was it. I was turned away from every job I applied for until I won my rehabilitation. Before then I was seen as a criminal.”

It took another two years of lodging petitions to the general prosecutor until Yury was finally fully rehabilitated in 1957. Now he breathes a sigh of relief that Russia’s Communist Party won’t win a general election any time soon. “But,” he whispers, “that dreadful motto we lived under for such a long time – ‘whoever’s against us will get it’ – hasn’t died yet.”