From Christmas movies to pop songs to motivational posters, we are encouraged to keep putting “one foot in front of the other.” While the sentiment is inspiring, recent studies show that there is a lot more to the seemingly simple task of walking than this phrase would suggest. Understanding this is especially important for balance and mobility after an injury or as people age.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

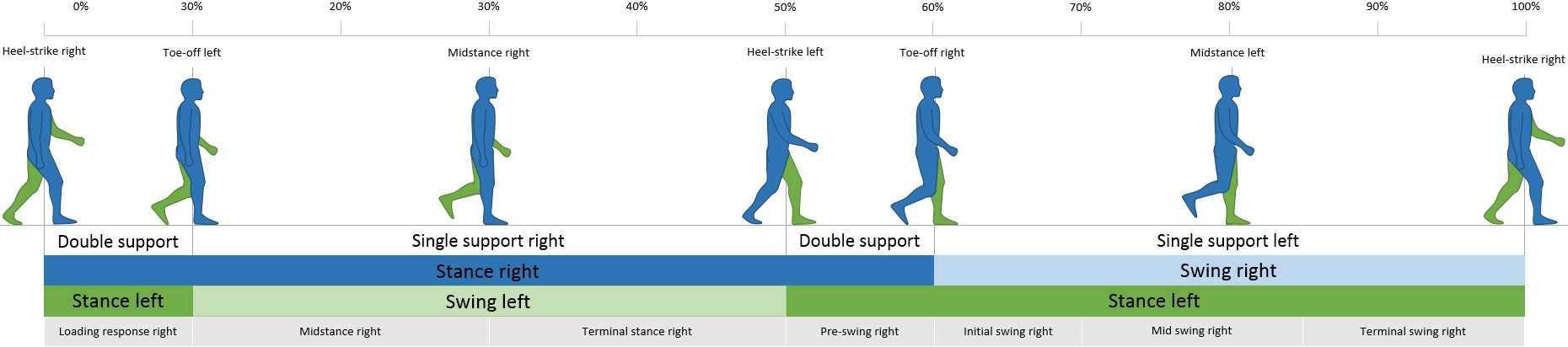

The human gait has a set structure that switches the weight between each leg, with only 20% of the typical walking motion distributing the weight across both feet. Maintaining balance throughout this process requires coordination in the muscles controlling the hips, knees, ankles, and feet. Mechanically, these adjustments keep the body’s center of mass (also known as center of gravity) over the base formed by feet positioning.

Obstacles and challenges to balance require a body’s quick response to mitigate shifts in the acceleration and momentum at the center of mass. Lack of efficient control over these parameters results in a fall. Many conditions, as well as age, can affect a person’s ability to respond to mobility challenges.

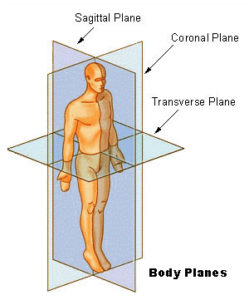

One specific study looked at how people who had had a stroke and subsequent partial paralysis on one side (paresis) faced mobility challenges compared with healthy folks. This condition effects approximately 400,000-500,000 people in the United States annually. It presents a unique opportunity to compare an individual’s non-damaged stride with their deficient stride at the point in the gait at which only one leg is on the ground (SLS, or single-leg-stride). The timing of the gait, the body’s momentum in all three planes of the body, and the location of the center of mass were recorded in this study.

Versus healthy people, stroke survivors had significant trouble regulating momentum in the coronal plane, making falls more likely. Although it makes sense that momentum regulation suffers when muscles are paretic, it is yet unclear why the coronal plane was most affected. Additionally, post-stroke individuals’ centers of gravity were higher, which is also linked to instability. For stroke survivors, the partially paralyzed SLS took longer and extended farther from the center of mass than the regular SLS. While this is not as immediately dangerous as increasing falling risk, it slows mobility, unevenly works muscles (which can lead to injury), and is less efficient.

Going forward, these findings can be used to improve mobility success in people with balance issues or after injuries. This could manifest in better technologies, such as walkers that better help settle a person’s center of mass and partial exoskeletons that would help a person mitigate acceleration and momentum changes, or more targeted and individualistic physical therapies to strengthen weakened muscles and practice patient-specific challenges, such as overcoming obstacles that threaten coronal-plane balance. Understanding more about balance adjustment when walking may make some common phrases trite, but its potential benefits have life-changing impacts for many.

Further Reading and Sources:

Featured image cropped from “Pedestrian crossing sign” by DennisM2 which is marked with CC0 1.0.