A surgery? For my PCL? Could be more likely than you think.

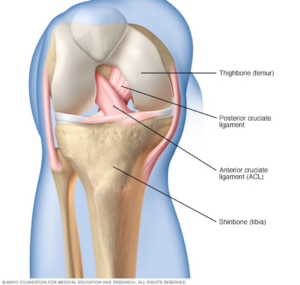

Usually hiding behind it’s annoying and commonly ruptured brother the ACL, the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament) is a durable ligament that usually doesn’t cause problems for athletes… until it does.

Because of the strong nature of the ligament, injuries that tear the PCL are usually sudden and traumatic. Think car accidents, falling hard on a bent knee… you get the picture. When enough force is applied to the top of the tibia, the tibia can be pushed backwards, past the threshold of the PCL. Even though the PCL does its best to hold your femur and tibia together in the right spot, it just doesn’t hold up to the brute force of a dashboard. These injuries can usually be diagnosed by the presence of a “sag.” When your doctor holds your bent knee up, it looks like your shin bone is sagging underneath your knee. This is your torn PCL crying for aid.

When it comes to fixing these injuries, the nonsurgical approach has typically been recommended for low-grade tears that don’t totally rip the PCL apart. These braces are attached to the leg right above the knee, and are supposed to hold the bottom part of your leg under the knee in place. This prevents from your knee from going too far forwards and backwards, and allows scar tissue to build up over your PCL. While your body tries to heal itself with scar tissue, you will work with a physical therapist to build up your quad strength and restore your range of motion. Over 80% of athletes are able to return to play after bracing their knees.

However, surgery, which was once only reserved for extreme PCL tears, is now seen as a viable, cost-efficient option for even low-grade tears. PCL surgery is intended to restore normal knee biomechanics and stability to about 90% of their post-injury strength. Sometimes, a part of the Achilles tendon is used to create a graft, or a “new” PCL. This is called an allograft, and results in safer and shorter surgeries (8). Within a month, the athlete can walk and bear their own weight. After six months, athletes are able to return to sports.

In theory, surgery sounds like the most “permanently good” option there is for fixing your PCL. However, no scientific studies have yet been done that can accurately compare the return-to-play rates, or even the relative healing of people in braces versus people who immediately got surgery. When people don’t comply with their treatment plans (aka, take off their braces early, skip physical therapy after surgery, etc.) the data for comparisons between bracing and getting surgery aren’t clear. While your PCL may be out of commission, so is the jury on this one. At the end of the day, the best treatment method for you is dependent on the mechanism of injury, severity of your injury, and whether you plan on listening to your doctor or not!

For more info on PCLs:

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Featured image under Pixabay License