In America we generally divide ourselves along two very specific lines. That is, we traditionally group ourselves up by class and race/ethnicity. If you are poor and black, for example, you will feel like you share almost no common experiences with someone who is rich and white. This is easy for us to understand as these two people would have no common ground along the two great American divisors, as I call them. The question arises, then, what about when two people share one of these things in common? Which divisor holds more weight – class or race/ethnicity? Does a rich black person have more in common with a poor black person or a rich white person? While the question may seem tasteless, I think that it is exactly what Dorothy B. Hughes is exploring in her novel The Expendable Man.

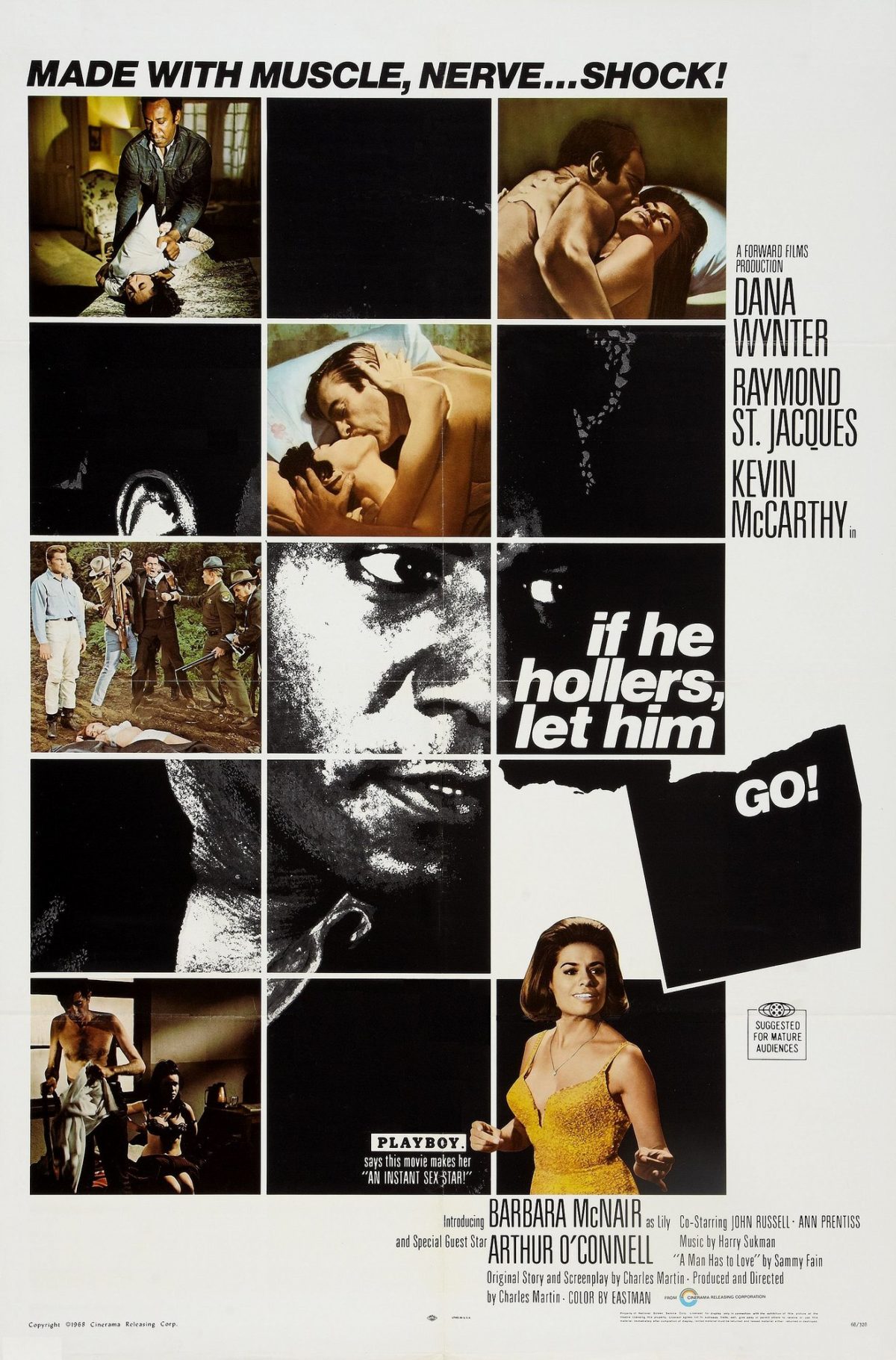

As we discussed in class, the entire purpose of this class is to take the classical racial and moral ambiguity of noir and thrust it on to the main stage. By construction, this means that the books we read will have race playing a major role in them. In If He Hollers Let Him Go, race was so central to the plot that it would be impossible to imagine any similar story without it, and while class was part of the story, it was not the main operator. Hughes, however, brings class much more in focus alongside race. Simply from a chronological standpoint, the book immediately makes clear what the class of Hugh Denismore is and how it contrasts to the class of Iris Croom (aka Bonnie Lee Crumb). While potential signals are given for what race each belongs to, nothing explicit is mentioned until the plot has already gotten well underway. Such an order of operations seems absolutely deliberate, and I believe that it may signal Hughes’s belief that class is a larger divisor in America than race is.

Whether someone is apt to agree with this assessment is largely based on personal experience, and writing in the 1960s would certainly not lend itself to the idea that class mattered more than race. With that said, I think that today in America (at least in the area that I know best) class really does play a bigger role in dividing us than race does. While there is no question that this is a debatable claim, I am interested to see how both aspects of American life play out in this book and the books moving forward. I think I would be very interested in writing about this for my larger paper towards the end of the semester.

I agree with your assessment of Hughes putting class first as the major divider in American society, and I do think that has to do somewhat with her background as a white woman. However, I disagree with Hughes and would say that race is the major divider in American society, but it’s also important to recognize that race and class are connected, especially in the United States, when considering the history of slavery and capitalism as a somewhat inequitable system. Having taken courses on race and class in the United States and looking at examples throughout history, what has often hindered the lower class from recognizing their mutual interests against the “1%” is racial differences. However, I do agree with your observation that which divider one views as greater is definitely dependent on life experiences, which is possibly why authors such as Chester Himes and Dorothy Hughes are choosing to highlight different dividers in their works.