Local news blunders are an easy mark, but it’s not easy to make a local news parody quite this funny. The late Don Ehninger was just that good in this sketch from 1968, BOC’s very first season. The expert comedic timing of the editing here also indicates that BOC would come to deliver not only funny performances but also aesthetic dynamism and technical savvy, even as it was making fun of the lack of it in local production.

Month: July 2023

BOC: WNDU’s Chalkboard and Textbook

Image source: Radio Age, October 1955, page 4.

Part of why I’m so excited about this project is because it’s about so much more than just one TV series; it’s also a portal into a history of local television, production technologies, and styles of comedy and evolutions in youth culture, education, and public service.

Highlighting just one small thread of the BOC tapestry in this post, nearly as unique as Beyond Our Control itself was the pedigree of the station that aired it. NBC-affiliated WNDU was owned by the University of Notre Dame from the station’s founding in 1955 until it was sold to Gray Television five decades later, and the studio was located on campus grounds until 1982. (To see where, check out the map within this post about the station’s construction and dedication.) The university’s launch of a commercial network station was so notable that WNDU’s dedication was attended by none other than David Sarnoff, head of RCA, founder of NBC, and the most powerful person in U.S. broadcasting in the 1950s. During a special academic convocation at Notre Dame on September 30, 1955, Sarnoff told the 3,000 people assembled, “Television on the campus is the modern counterpart of the blackboard and textbook. In your Convocation Program, I note Father Hesburgh’s statement that ‘a university can no more ignore television today than universities of the past could have ignored the discovery of printing.'”

WNDU would indeed help foster broadcast education in taking on Notre Dame students as interns, but nothing made more of an educational mark within those studio walls than Beyond Our Control. Creator Dave Williams and the other advisors made it the “chalkboard and textbook” that Sarnoff foretold while fostering wisdom about a lot more than just television production. Given the station’s location, it’s additionally worth noting that, due to Notre Dame admitting only men up until 1972, the teen girls who were part of BOC in its first four years would have been among the only women receiving an education on Notre Dame’s campus at that time. (Read more about the more than 4,5000 women who did actually graduate from Notre Dame before 1972 here).

Bonus material: Click the ‘Play’ icon here to listen to Father Hesburgh’s first address to WNDU audiences as the station went live on July 15, 1955.

“It is our finest hope that through the medium of television, we will be able to bring to this whole community the many fine things that Notre Dame stands for here in South Bend. We would like you to feel that this is your station, that through this station, you are brought all of the fine elements that Notre Dame does stand for, that through your cooperation, we can make this station a fine and vital influence in this community for everything that is good.” — Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, July 15, 1955

And if you’re more interested in broadcast personalities than broadcast presidents, check out WNDU’s article on another prominent pair of guests invited to campus for the festivities: Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds. (This dedication was a big deal, folks!)

BOC Sketch of the Week #1

I’m going to post a Sketch of the Week here each Monday (or maybe Tuesday or Thursday or whenever I remember to post one). It might be something that I found particularly intriguing that week, or sometimes I’ll try to tie them in with current events.

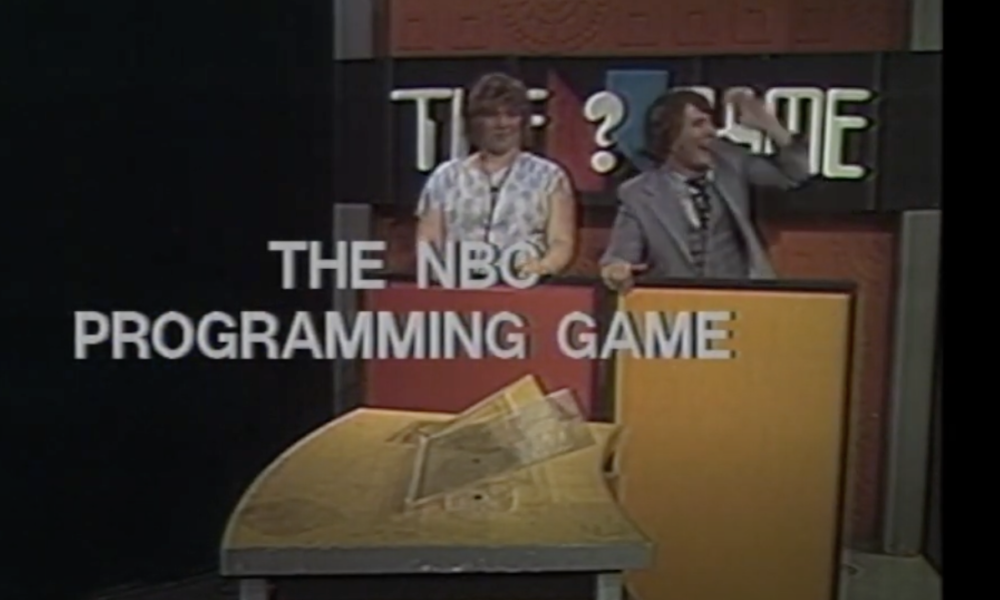

The most important current event in the entertainment business is the SAG-AFTRA and WGA labor strikes. As a reminder that entertainment execs have always seemed myopic and don’t truly know what people want to see, check out this 1979 sketch in which Larry Karaszewski plays BOC’s real network boss, NBC president (and previous CBS and ABC programming chief) Fred Silverman.

Silverman got on the cover of Time magazine in 1977 with a profile headlined “The Man With the Golden Gut,” but his gut apparently soured by the time he got to NBC in 1978, where he had a number of high-profile failures (including a few with McLean Stevenson). Even kids know TV execs are full of it!

Fun facts: Karaszewski previously played a spinoff-obsessed Silverman at the end of “Son of Jed”, a future Sketch of the Week candidate. Also, let it be noted that BOC took on Silverman well before Saturday Night Live did in this blistering Weekend Update bit from Al Franken.

Segment info: “The NBC Programming Game,” aired in 1979, starring Mark Wilson (host), Larry Karaszewski (Fred Silverman), Juliet Davis (Alice Thorndike from Scranton, Pennsylvania).

What Am I Doing Here?

Photo caption: Members of the 1968-69 crew of Beyond Our Control in the WNDU-TV studio.

My name is Christine Becker, I’m an associate professor in the Dept. of Film, Television, and Theatre at the University of Notre Dame, and I’ve started this site to chronicle my process of researching and writing a book about the 1968-1986 sketch comedy TV series Beyond Our Control, which was produced in South Bend, Indiana, almost entirely by high school kids. If you don’t know what this show is, the Wikipedia page is a good place to catch up quickly, or you can check out the BOC Alumni Association’s website and its history post, or watch sketches on YouTube here, here, and here. I plan to showcase materials from all of these sources as I go, which will hopefully engage fans of the show and also help me work through ideas along the way. I encourage anyone who has thoughts or memories to share (or – the ultimate dream – intact pre-1978 episodes) to get in touch with me or add comments to a post. I want to know everything, so no comment or query is too small!

For now, I’ve pasted below the opening paragraph for a short (6000-word) essay I’ve already written about the show, which will be published in 2024 by UGA Press in a collection titled Local Television: Histories, Communities, and Aesthetics. The book version will be about a lot more than just the “intricate balance of multiple intertwined forces” that made the series possible, as it says here. The show is nothing less than a portal into the history of local TV, youth culture, comedy, education, and public service, in addition to a fascinating personal story. But hopefully this is at least an engaging tease to start.

“Imagine for a moment you’re 17 again. You’ve grown up with television as your babysitter, your educator, your entertainer. But now much of what television is doing somehow fails to interest you. You’re turning it off — simply because most of the time it’s turning you off. And then someone asks, ‘What would you do if you were given a half-hour of television time to fill each week?’ For 25 teenagers in South Bend, Indiana, that question is being asked. I’m one of those doing the asking — and we’re expecting not only a good theoretical answer, but an actual half-hour program.” — Dave Williams (1971)

Williams, Dave. 1971. “Beyond Our Control — a Junior Achievement Television Program.” Educational Television, April: 11-14.

That actual half-hour program was Beyond Our Control, a sketch comedy series that aired on WNDU-TV, an NBC affiliate in in northwest Indiana, for thirteen weekends in the first quarter of each year from 1968 through 1986. The series was a product of a nonprofit youth initiative called Junior Achievement, which aimed to teach high school students principles of economics and free enterprise. Under this mission and the guidance of creator Dave Williams and a handful of other adult advisers, South Bend-area students between the ages of 14 and 18 undertook nearly every job required to put a commercial TV series on the air, from writing scripts to operating studio cameras and switchers to selling commercial time. Beyond Our Control was billed as “A TV show about TV,” featuring parodies of local and network news, prime-time dramas, sitcoms and variety shows, daytime game shows and soap operas, B movies and art cinema, and nature documentaries and commercials, as well as the occasional epic serial, experiemental film, or animated bit. As such, the series is a remarkable document of American televisual culture across two decades, as well as a gauge of how teenagers in the Midwest assessed the entertainment in which they were steeped. Nineteen years is a very long stretch for any TV series to survive, let alone one made by teenagers with annual labor attrition enforced by high school graduation. A “good theoretical answer” is thus required to explain how the actual half-hour program worked for as long as it did, in the particular city in which it did, and in the format that it did even starting well before its famous national counterparts like Saturday Night Live were conceived. That answer is neither simple nor singular, and it demands understanding of an intricate balance of multiple intertwined forces.

Due to Circumstances…