Race is a social construct that was created to categorize people and justify the atrocious acts of slavery and oppression. In reality, there is more genetic variation found within a racial group than between racial groups (Wu et al., 2005). Although race is not biological, the lack of healthcare access and significantly worse healthcare outcomes present in communities that suffer from poverty, oppression, and racism are staggering when compared to the outcomes found for the wealthiest Americans. Social determinants of health, racial domination, and racism in medicine are the root causes of this disparity found in the United States today. As someone who has parents that were born and raised in Mexico, I have seen firsthand the impact that poverty and lack of healthcare can have on racial minorities, especially with the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Defining Social Determinants of Health

I grew up in a very small town in west Omaha, Nebraska, which is a predominantly white community. I was the only person of color in my elementary school and middle school. I would notice that the houses were nice and my education system was great. Since we had many family members and friends who lived in south Omaha, where there is a predominant Latino presence, I would notice the instant differences between these two parts of the city. There is an abundance of fast food chains in south Omaha along with beaten down buildings, cramped housing, and trash accumulating on the streets. At this young age, I did not know that these differences in living conditions would cause staggering differences in health outcomes.

Social determinants of health are defined as where people live, work, play, and age that affect a wide range of health functioning along with the quality of life outcomes and risks (“Social Determinants..”). They can be divided into domains which include economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social community context. Some examples of how these domains can affect health outcomes include being exposed to polluted air and water along with having access to safe housing and transportation (“Social Determinants..”).

Income Inequality Across Different Races

Social determinants of health are the primary contributors to health disparities and inequalities since they can lower life expectancies and raise the risks of health conditions like heart disease and obesity. Since social determinants of health include where people live and the education people receive, it is no surprise that income plays an important role. Almost every chronic condition follows a pattern of rising prevalence with declining income. It is no surprise that racial minorities, such as Hispanics and African-Americans are the ones that face the lower end of income inequality, and therefore experience the worst health outcomes. In 2013, the median family wealth for the white population was more than 10 times that for Hispanics and 12 times that for African-Americans (Dickman et al., 2017). It does not help that the U.S. healthcare system contributes to this inequality because many people are not able to afford expensive medical care and high cost-sharing since the U.S. is by far the world’s most expensive medical care. Since the most burden is placed on the uninsured, they delay seeking medical care which causes a rise in their preventable deaths (Dickman et al., 2017). Likewise, there is strong evidence that the quality of care is worse for racial and ethnic minorities. For example, African-Americans are more likely to live closer to high-quality hospitals, but they are less likely to receive care there (Dickman et al., 2017).

It is evident now that social determinants of health, such as income and where someone lives, have a greater effect on the health outcomes of certain people. This can explain why the Hispanic and African-American population is more likely to have certain diseases, especially in light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Black and Latinx people are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than white people in the United States (Maxmen, 2021). Even from a young age, the differences I would experience in a predominantly white population compared to a Hispanic population are proof of the drastic difference that income can have on one’s living conditions.

Recent COVID-19 Pandemic on Racial Minorities

The racial disparities found in the U.S. healthcare system are most noticed in the recent COVID-19 pandemic. I vividly remember how the pandemic affected everything around me. I was worried for my dad who still had to go to work because his job could not be remote. It upset me how there was no intervention or virtual option available for people like my dad. Most of the jobs that could go remote were the ones of office jobs or middle-class jobs that most racial minorities do not have. Many immigrants or minorities were not able to be cautious because they needed to work to maintain their families. It is upsetting to know that poverty and discrimination drive disease but so little is done to help with these disparities.

“Farmworkers don’t stop for a pandemic,” he says. “We keep working.”

“Inequalities Deadly Toll” (Maxmen, 2021)

As someone who grew up as part of the Latino community, I have heard quotes very similar to the one above. Almost everyone I knew continued working despite all the CDC recommendations because they would have no other ways to pay for bills and food. Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people have been affected by COVID-19 more than white people in the United States. Latinx food and agriculture workers experienced a nearly 60% increase in COVID-19-related deaths compared with the previous years when the increase for white workers was only 16% (Maxmen, 2021). It is upsetting that the U.S. relies on immigrant labor yet they are not provided with a living wage or affordable health care, although they are paying taxes.

Lack of Healthcare For Immigrants

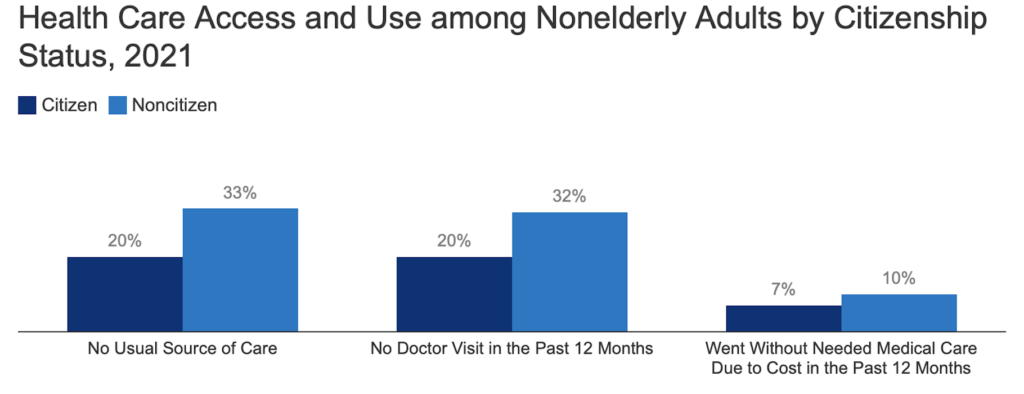

The uninsured face the greatest barriers to care, and among the non-elderly population, one in four lawfully present immigrants, and almost half of the undocumented immigrants were uninsured (“Health Coverage..”). Because many of these people do not have insurance, they are less likely to access healthcare even when they need it. The high cost of healthcare in the U.S. does not help as 33% of non citizens have reported not having a usual source of care and 10% not going with medical care due to its high cost which is shown in the figure below (“Health Coverage..”).

Immigrants are not the only population that suffers from lack of health care, but also many citizens in the United States. Action must be taken to reduce these racial disparities that stem from differences in social determinants of health. It has been known for decades that poverty and discrimination drive diseases, and, unfortunately, COVID-19-related deaths is just another demonstration of racial inequality.

References

Dickman, Samuel L., David U. Himmelstein, and Steffie Woolhandler. “Inequality and the health-care system in the USA.” The Lancet 389.10077 (2017): 1431-1441. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673617303987. Accessed 20 February 23.

“Health Coverage and Care of Immigrants.” KFF, 20 December 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-and-care-of-immigrants/. Accessed 18 February 23.

Maxmen, Amy. “Inequality’s deadly toll.” Nature (2021). https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-021-00943-x/index.html. Accessed 18 February 23.

“Social Determinants of Health.” Social Determinants of Health – Healthy People 2030, https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health. Accessed 18 February 23.

Wu, Zheng, and Christoph M. Schimmele. “Racial/ethnic variation in functional and self-reported health.” American Journal of Public Health 95.4 (2005): 710-716. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2003.027110. Accessed 19 February 23.