Mae Czerwiec • March 26, 2023

During the AIDS epidemic, my aunt, MK Czerwiec, served as a nurse in the AIDS Unit at Illinois Masonic Hospital in Chicago, IL. Like any nurse, the stories of the terrible things she saw during her time are multitudinous, and the experience was rife with emotional heaviness. But unlike other nurses, she was encouraged to be creative, break the rules she’d learned in nursing school, and provide care to patients through non-traditional medical and non-medical methods (Czerwiec 2017). In the 1980s and 90s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the US, patients required more care than medicine alone could provide them.

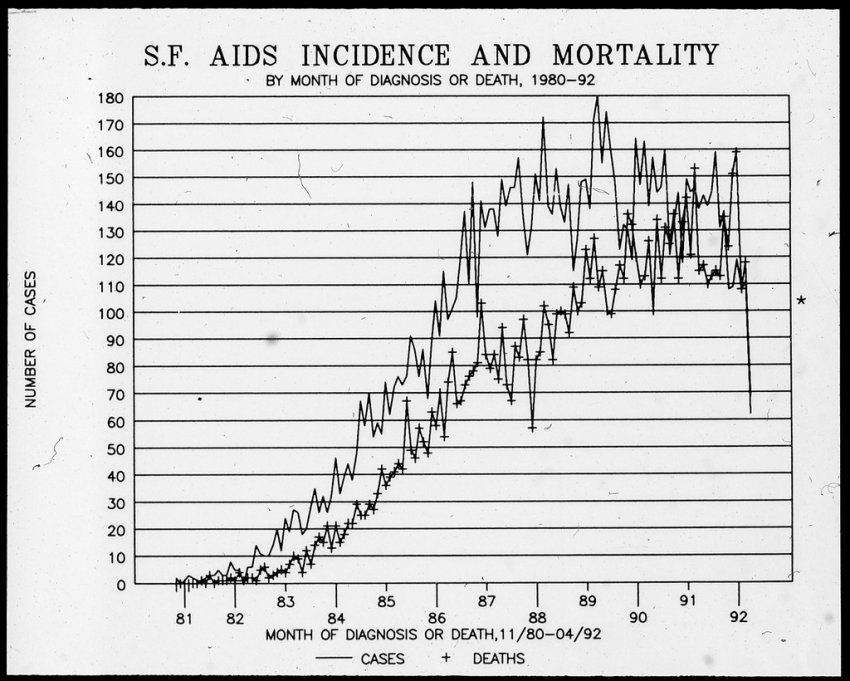

Six years into the AIDS epidemic, the mortality rate was nearly 100% (France 2012). Doctors didn’t know what caused it or how it spread: it was new and terrifying. Affluent, otherwise healthy young men began showing up to emergency rooms with skin lesions that were hallmark signs of Kaposi’s Sarcoma, and pneumonia would kill them soon after (France 2012). As it became apparent that the disease had a disproportionate prevalence in LGBTQ+ populations, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM), anti-gay backlash ensued against victims of the disease– from laypeople to lawmakers, there were many who believed these men were being deservedly punished for their moral sin (France 2012). Even as municipal hospitals in hotspots like New York City became overwhelmed with AIDS patients, there were incentives not to diagnose the disease; after all, if it was diagnosed, the government and the medical establishment would have a duty to find a treatment (France 2012).

In his book The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition, author Arthur Kleinman emphasizes that in our society, illness has meaning. It has significance. Illness is not merely something that happens to us, but something that we are. “[L]ike a sponge,” Kleinman writes, “illness soaks up personal and social significance from the world of the sick person” (Kleinman 1988, 31). In the case of the AIDS epidemic, patients were not only sick with a disease that was rapidly-progressing, disfiguring, and generally fatal within a few years, but they were made to believe that their illness was their own fault, and that they deserved both the physical suffering and the social disgrace that accompanied it. This is what Kleinman and others refer to as stigma, and for the LGBTQ+ community, it was almost as crippling as the epidemic itself. Historically, stigma described a physical mark of public disgrace, akin to the Star of David forcibly sewn onto the clothes of Jewish people by the Nazi Regime, although over time, stigma has come to refer to the shame more than the mark (Kleinman 1988, 169). Patients who died of AIDS in hospitals were often put in black trash bags, and some funeral homes refused to hold their services (France 2012). Even queer people who weren’t marked with the physical symptoms of AIDS, like Kaposi’s Sarcoma, were subject to the stigmatization that resulted from the disease. Battling both an incurable disease and an unfavorable public image, how were victims and advocates to respond?

The answer lies in forming communities of care.

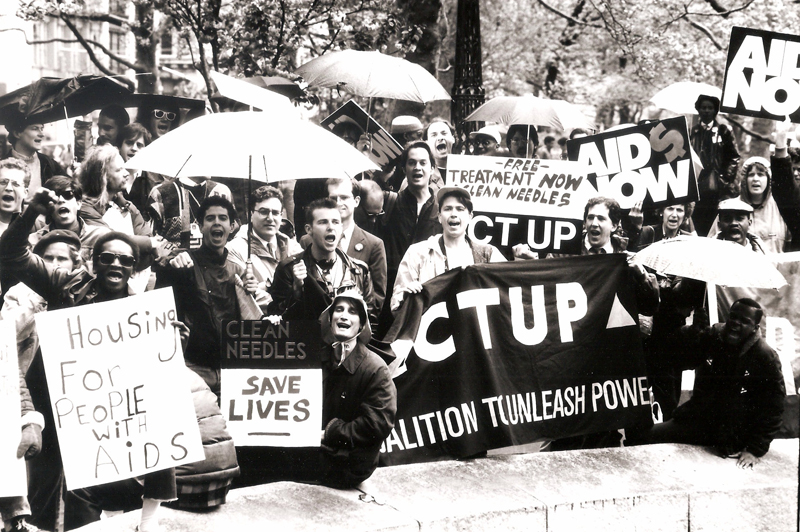

My aunt, mentioned earlier, is a lesbian, and she saw part of her care for AIDS patients as a duty to her community. And a lot of AIDS nurses were lesbians– the TV series Pose on Hulu, which highlights Black and brown ballroom culture of the 1970s and ‘80s, features Sandra Bernhard playing the feisty and tenacious Nurse Judy– who also felt called to stand up for and support fellow queer people. But medicine was just one part of the AIDS care network. Also of importance was collective health advocacy, seen most notably in the work of the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP), an AIDS activist group formed in New York City in the 1980s. One member described ACT UP as a group of “artists and hipsters” who came together to gain the scientific knowledge of AIDS and the virus that causes it (HIV) necessary to meet politicians and scientists at their level and push for real change (France 2012). They were eventually able to persuade Dr. Anthony Fauci and the NIH to allow lay AIDS activists to sit on their advisory boards and have an input in the process of AIDS research and drug development. The involvement of both gay and straight scientists and professionals who were willing to do this educational work also formed parts of these care networks. One activist remarked that he believed every AIDS drug that is available today has ACT UP at least partially to thank (France 2012). Without groups of diverse but like-minded folks coming together to provide a common good for each other, the already-delayed response to the AIDS epidemic would have resulted in devastating outcomes.

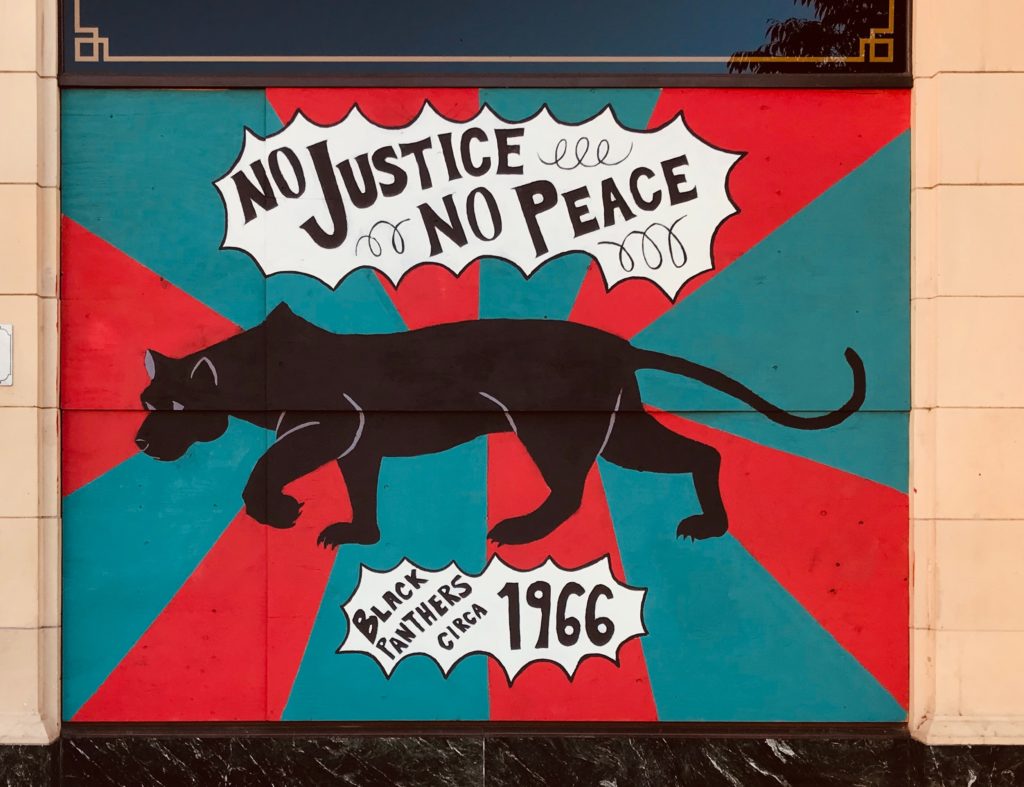

The power of care networks isn’t restricted to those with stigmatized illnesses like AIDS. The medical establishment is often hostile and ineffective for people of color, regardless of their perceived health status. In the 1970s, the Black Panther Party responded to this systemic neglect of Black patients by forming its own health program, concentrated in the local facilities known as the People’s Free Medical Clinics (PFMCs) (Nelson 2013). The clinics were created in direct response to the Party’s perception of the “circumstances surrounding illness” in the treatment of people of color, which resulted in their avoidable deaths at institutions of white medical power (Nelson 2013, 79).

Like ACT UP, the Black Panther Party was initially composed of laypeople, concerned citizens identifying as members of a marginalized group who had a thirst for activism but lacked the expertise to bring necessary resources to their respective communities. Part of the power of both organizations came from their ability to draw in professionals sympathetic to their respective causes who were willing to do the work of educating and supporting the ultimate goals of activists who may have been more personally invested in the cause. Most of these professionals offered their expertise on a volunteer basis; for example, University of Washington medical school students and faculty offered services to the Seattle-based Sidney Miller PFMC (Nelson 2013, 97). Once again, a diversity of skill sets, from organizing and advocacy to first-aid and education gave power and credibility to the health movement.

I think when we look back on these two health advocacy movements, it can be all too easy to relegate them to their respective moments in history. But it’s critical that we do not let these movements die with their founders– their struggles are not over. We know that Black people in the United States have significantly worse health outcomes than their white peers, particularly Black women of reproductive age (Hill, Artiga, and Ranji 2022). We know that there are over 35,000 new HIV infections in the US each year, with disproportionate effects on Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities (Kaiser Family Foundation 2021), and that LGBTQ+ rights are under attack every day– the ACLU is currently tracking 430 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in state legislatures (ACLU 2023). Thinking intersectionally, we know that all of these health risks are amplified for Black trans women and trans women of color. And we know what the answer is to these threats, because our communities have answered the call before.

In the last election cycle in my tiny hometown, the hot button issue was funding for public works, particularly budget allocations for local emergency services. One particular focus was on whether it was worthwhile to purchase a new ladder truck– devastating blazes are uncommon, opponents argued, and our small town’s funds would be better spent on other public goods; neighboring fire departments would be more than capable of providing us with their aid should we require it. But the supporters of the fire truck were adamant. Overnight, signs popped up in front yards up and down our little blocks: WE NEED OUR OWN TO SAVE OUR OWN! Perhaps the fire truck metaphor is silly, but this is what I think of when I think of health advocacy and activism. The work only gets done when those of us who are affected the most deeply rally together around a common cause. Change happens within communities. When we shout together, our voices echo.

References

- ACLU. 2023. “Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in US State Legislatures”. https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights

- Czerwiec, MK. 2017. Taking Turns. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

- France, David, director. 2012. How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects. 109 min.

- Hegedus, Eric and Robert Rorke. 2019. “Sandra Bernhard: ‘Pose’ recalls horror of early days of AIDS”. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2019/06/21/sandra-bernhard-pose-recalls-horror-of-early-days-of-aids/

- Hill, Latoya, Samantha Artiga, and Usha Ranji. 2022. “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them”. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. “The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Basics.” https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/the-hivaids-epidemic-in-the-united-states-the-basics

- Kleinman, Arthur. 1988. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. Basic Books.

- Nelson, Alondra. 2013. “The People’s Free Medical Clinics” in Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota Press.