If you asked me to summarize my experience of living and working in the Philippines in one sentence, I would say, “In the past month I have experienced both extreme feelings of familiarity and strangeness.” Beyond the contradictions, this combination has been an interesting opportunity to reflect on myself and my future professional life.

Getting out of my comfort zone

For my Master of Global Affairs i-Lab project, I am working in partnership with the Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter (TCIS) at Habitat for Humanity to improve how market analyses are conducted by international aid organizations within the shelter sector. Specifically, we are testing the market analyses process in one of the areas hit by Super Typhoon Yolanda in 2013. Despite my prior experience with humanitarian assistance, diving deeply into the shelter sector has certainly pushed me outside of my comfort zone.

You are probably inquiring why would a market analysis be relevant at all? I will try to answer briefly: When a crisis occurs (after an earthquake, a typhoon or a massive displacement), local market actors are often the principal means by which people obtain essential items they need to recover and adapt. In the past, this was largely ignored by international aid organizations, who often imported and distributed goods and provided services directly to those affected. These actions bypass and hinder the resources and capacities of local communities. For this reason, in recent years, humanitarian organizations have started to support and use local market supply chains in their aid response.

Advocates for this type of market intervention argue that it supports livelihood opportunities, improves economic rehabilitation and helps international organizations adapt better to the local context. This all sounds great, right? However, to support such interventions, organizations need to understand the local markets, and when it comes specifically to the shelter and housing sector, aid organizations are still struggling to do so. That is where our partnership with TCIS comes in.

The experience of a Colombian in the Philippines: The familiar within the unfamiliar

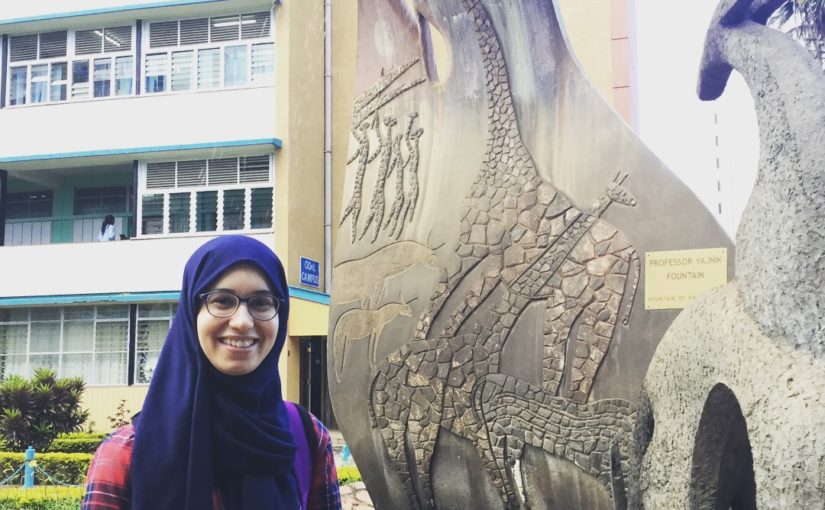

During our time here, we have been conducting interviews with families, masons, carpenters, local hardware stores and wholesalers to map the capacity of the local market systems to meet the housing demands of low-income households (including land tenure, financing, access to materials and labor). I am marveled by how willing people have been to share their knowledge, thoughts and experiences with us.

Every time we conduct interviews with households, families usually offer us a snack. This gesture has immediately transported me back to my days of fieldwork in Colombia, where I was always offered a cup of coffee and some bread or cookies when I visited someone’s home. More generally, Filipino architecture, cuisine and religious traditions— strongly influenced by Spanish colonization— together with the warmth of the people and their commitment to build a more peaceful and inclusive society amid challenging conditions of inequality and violence, have made me feel at home.

Despite these similarities, and the fact that most first and last names in the Philippines are in Spanish, I have not encountered a single person who speaks the Spanish language. Getting by in the cities has been surprisingly easy for our team, as almost everyone we interact with speaks English. Yet, in rural areas the use of English decreases significantly. Because of this, we are conducting our interviews in Cebuano, the language most widely spoken in Cebu province. To make this possible, we have a Cebuano on our team, who has not only acted as a translator, but has also helped us navigate our daily life here and helped us establish contact with different stakeholders.

Although it has been great working with him, it has also been frustrating not being able to participate in these interviews because it limits our capacity to build relationships and to analyze the situation from first- hand information. This is a completely new experience for me, and it has really made me reflect on the importance of relationships, cultural sensitivity and language training in development work.

Reflections from a safe exposure

Although there is no doubt that international agencies supporting local economies is a step forward in the process of localizing development, I cannot help but wonder if these solutions are still rooted within the systems and power relations that intrinsically constitute an obstacle for the development of these communities. Does the analytical assessment of local markets by outside organizations inherit certain biases? One of the biggest challenges we face is to resist being absorbed by a technocratic mindset that ignores other aspects of social dynamics. Focusing solely on technical issues becomes a barrier for change because it eclipses the human components and does not contest the unequal power relations that hinder structural transformations.

Strangely, one of the things that I have found most enriching about this experience is the feeling of discomfort. This project has forced me to venture into a new region, a new culture and a new sector. Being here on our own, but having the support of the Keough School and our advisor Tracy Kijewski-Correa, has been a safe exposure and in my case, a chance to experiment with a completely different professional career path. Every day I ask myself how I would feel if this were my long-term job and what would be different if that were the case. I am sure these reflections will continue to grow as I continue my experience here and will certainly be useful as I start to think about what I want to do after I graduate.

Spanish classes—my first exposure to Spanish! While the rest of my classmates are enjoying a three-week post-semester holiday, I am enjoying my Spanish classes and my busy, yet never the same, schedule in Chile.

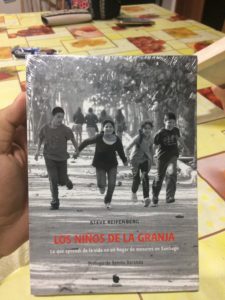

Spanish classes—my first exposure to Spanish! While the rest of my classmates are enjoying a three-week post-semester holiday, I am enjoying my Spanish classes and my busy, yet never the same, schedule in Chile. In Santiago’s Children, Professor Reifenberg talks about his experience working for Domingo Savio in the 1980s when he visited Chile right after the college, not knowing Spanish well. The stories described in the book are so authentic that they bring you into author’s life 35 years ago and make you see it from his eyes.

In Santiago’s Children, Professor Reifenberg talks about his experience working for Domingo Savio in the 1980s when he visited Chile right after the college, not knowing Spanish well. The stories described in the book are so authentic that they bring you into author’s life 35 years ago and make you see it from his eyes.