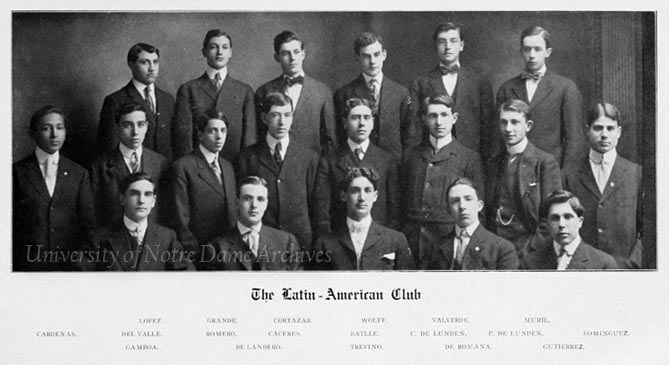

Part of Notre Dame’s expansion in the second half of the 19th century came from active recruitment of students from Mexico, Cuba, and other parts south of the border. Considering the high percentage of Catholics among the people in Latin America, it made sense for Notre Dame officials to recruit Latin American students. According to Arthur J. Hope, “Early in Father [John W.] Cavanaugh’s administration [1905-1919], over 10% of the enrollment was from Latin America. Notre Dame was one of the pioneers of the ‘Good Neighbor’ policy.”

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Notre Dame published advertisements, catalogs, and bulletins in Spanish for prospective students. Scholastic, the student-run weekly publication, also published issues in Spanish. By 1885, Notre Dame’s student population was so geographically diverse, it made economic sense to purchase a hotel train car. Rev. John A. Zahm was chaperone for these trips out West and south to Mexico City.

An author for Scholastic described the influx of these new types of students in 1883:

“A very promising scholastic year has just begun. The attendance of students is large—fully up to the expectations of the most sanguine friends of the University. Among them is an unusually large proportion of new students. Many of these are from Mexico and remote parts of the United States. This is a gratifying evidence of how widely known Notre Dame has become. It is likewise an indication of the confidence reposed in it as an Institution of high rank and solid merit by persons who live even beyond the limits of the great Mississippi Valley. This fact is duly appreciated by all friends of the University. But to those more particularly identified with its past and present interests—to those who have watched and labored as it grew up from a humble beginning to the high rank it now holds—there is a source of special gratification in the undoubted assurance of its prosperous present and more than promising future” [Scholastic, 09/18/1883, page 24].

While many Notre Dame administrators and professors traveled long distances to escort students to South Bend, Notre Dame also sought recruiting help from alumni and other benefactors. Sam Keeler was stationed in Havana, Cuba, with the United States Army in 1900 when he received a letter from Sister Aloysius, the director of the Minim program. He responded that he knew of a perspective student and he would surely pass along a catalog if she would send him one. Keeler replied that he was “[glad] to do anything that will benefit the school of my younger days. … I am sure he [the prospective student] will like Notre Dame as I did years ago when I was a boy at St. Edward’s Hall” [UPEL 77/04].

Cuban businessman Carlos Hinze, originally from Prussia, sent his family to Muncie, Indiana, in the late 1890s to escape the dangers of the Spanish-American War while Hinze stayed behind in Havana. Hinze sent his son Carlos to Notre Dame and daughter to Saint Mary’s Academy. With his connections in Havana, Hinze became a go-between with the Cuban families and Notre Dame, from recruiting new students to checking in on their progress at Notre Dame. As a business man, Hinze also asked Notre Dame officials for help in bringing Studebaker to Cuba [UPEL: Hinze].

Sources:

Scholastic

UPEL

PNDP 05/Hi-01

PNDP 05-Me-01

Notre Dame: 100 Years by Arthur J. Hope