Wednesday, April 23, 1879, started out as any other spring day at Notre Dame. Taking advantage of the warm day, the Minims were out on their play yard. Around 10:00am, they were the first to notice the smoke rising from the Main Building and sounded the alarm — “College on fire!” Notification was sent to South Bend and a fire engine was dispatched to Notre Dame, but it arrived too late to save five of the campus buildings that were quickly consumed. Despite several devastating fires in her past, Notre Dame was ill-prepared for such a large fire. Even though the Main Building was equipped with water tanks, they proved futile on this fateful day.

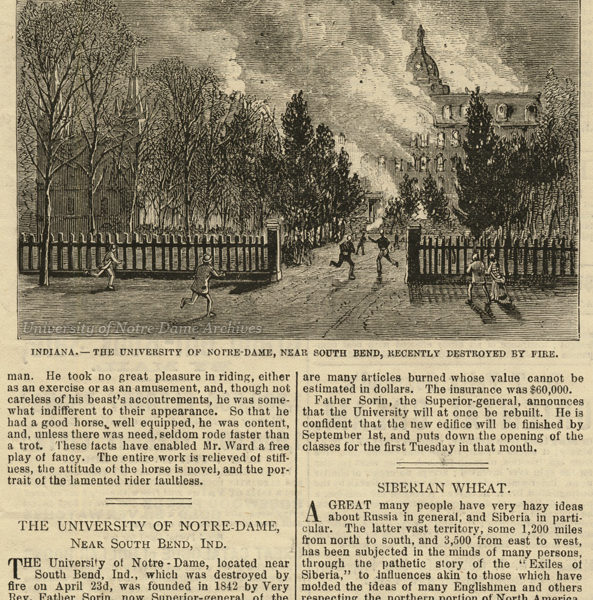

The origins of the fire are uncertain, but many theories point to construction work being done on the pitch roof of Main Building. As soon as the fire was discovered, students, faculty, and local townspeople scrambled to form a long bucket brigade up the six floors of the building. Many others desperately tried to save the precious library books, museum artifacts, scientific instruments, furniture, and personal effects. They carried many items carefully out of the buildings. However, in the chaos, some people frantically flung things out of the windows, destroying them from the fall in an attempt to save them. Once the wooden supports of the dome gave way, sending the one ton Mary statue plummeting through the center of the building, all chances for further recovery were abandoned. The western winds spread the fire from Main Building, additionally destroying the infirmary, St. Francis Old Men’s Home, Music Hall, and the Minims’ Hall. Fortunately, Sacred Heart Church (designated a Basilica in 1992) and Luigi Gregori’s murals were spared, as were the Presbytery, the printing presses (home of Ave Maria and Scholastic in what is now Brownson Hall), the kitchens, the steam house, and the first Washington Hall (the current one was dedicated in 1882).

The fire raged for only a few hours and was relatively under control by evening. The South Bend fire engine remained on watch for any flare-ups. Miraculously, there were no fatalities and only a few injuries – student PJ Dougherty either jumped or fell from the third story and recovered quickly in a few days. Others narrowly escaped falling debris that could have been deadly. Main Quad was strewn with items that were salvaged from the burning buildings. In all, there was over $200,000 worth of damage, including 25,000 books, 17 pianos and other musical instruments, many valuable scientific specimens, and irreplaceable historical artifacts. Insurance only covered about $45,000.

[photoshelter-img i_id=”I0000mB2wWapbs1A” buy=”1″ caption=”Engraving of campus with the Basilica of the Sacred Heart and Second Main Building before the fire, c1870s” width=”600″ height=”432″]

At 3:00pm, the administration and faculty convened to map out a game-plan for the immediate future of Notre Dame. They decided that the school year should terminate early. They began making arrangements to send the grief-stricken students home and confer degrees early, but no one believed this was the end for Notre Dame. University President Rev. William Corby decided immediately that the University would rebuild and would be ready to accept students at the normal opening day in September. Scholastic writers echoed, “we feel that there is no reason to give way to discouragement. No, we cannot bring ourselves to believe that the sun of Notre Dame has set. Let the thousands of loving children whom she has sent into the world within the past quarter of a century — let the devoted friends whom she counts in all parts of the country but rally to her relief, and we have every reason to feel confident that the good work which she has been doing in the past will be continued in the not distant future” [Scholastic, April 26, 1879 issue, page 536].

Photos by James Bonney.

Rev. Edward Sorin, founder of the University, was in Montreal at the time of the fire, about to embark on his 36th transatlantic voyage. A telegram was dispatched to intercept him, although some feared the physical effects of an aging Sorin receiving the news. Professor James Edwards left South Bend for Montreal to tell the Superior General his first-hand account in person. Both of them returned to Notre Dame on Sunday, April 27th. That Sunday morning, thousands of students, faculty, and townspeople packed the Basilica of the Sacred Heart as Sorin preached “Lessons of the Fire,” in which he told them “If it were all gone, I should not give up.” Professor Timothy Howard recalled many years later that they were “the most sublime words I have ever listened to” (X-4-e, April 14, 1906).

What might have led other American institutions at the time to fold seemed to only embolden the Notre Dame spirit: “Yes, Notre Dame will be herself again in a few months with God’s help, the untiring toil of her children, and the aid of her generous friends who have never failed her in her hour of need. … Notre Dame has so grown into the life of the country that it cannot but live and flourish, notwithstanding the fire. Like a vigorous tree which has been burned to the ground, the life is still strong in the great heart beneath, and it will spring from its ashes more glorious and beautiful than ever.” [Scholastic, April 26, 1879 issue, page 534].

Once he returned to campus and surveyed the damage, Fr. Sorin seemed to spring back to his youth, determined more than ever to rebuild Notre Dame into a grander university. There was much work to be done and everyone pitched in as they could. Scholastic noted that Sorin could “wheel off a load of bricks with great grace and dignity” [May 10, 1879 issue, page 546]. Three weeks after the fire, the debris pile still smoldered and smoked. Visitors from all over came to see the ruins for themselves.

Engraving by Fernique published in “Annales de Saint-Joseph” of the College de Sainte-Croix, Neuilly, France.

News of the tragedy quickly spread across the country and into Europe. Letters and telegrams of support and promises of financial aid poured in. Notre Dame administrators, faculty, alumni, and benefactors immediately hit the bricks in raising funds to rebuild. Fortunately, their strong networks helped to make the rebuilding of Notre Dame a quick reality. Rev. John Zahm solicited specimens for his Museum of Natural History. James Edwards solicited books for the Lemonnier Library. Sorin solicited funds across the country and in Europe.

On May 4, 1879, Fr. Sorin blessed the cornerstone for the new Main Building, even though official architectural plans were still under consideration. By mid-May Chicago architect Willoughby Edbrooke was hired out of many architects who submitted their work in the nationwide competition. Hundreds of laborers descended on campus and construction worked at a fast pace. More than 4,300,000 bricks, mostly made from the marl in the lakes, needed to be laid by September. Sorin figured construction cost $1000-1500 a day and the lack of insurance already put them far behind. However, Sorin’s complete faith in Divine Providence never faltered. He noted to Sister Columba, “our catastrophe, so sudden and so unexpected and so terrible, has been seen as a loss to the whole country, and the American people have marvelously helped us to reverse it” [quoted in O’Connell, page 656].

[photoshelter-img i_id=”I0000abLeGWAmA2c” buy=”1″ caption=”The New Notre Dame – Engraving of Main Building exterior, 1879.” width=”600″ height=”478″]

The core of Main Building was complete for the opening school term in September 1879. Four months earlier, Notre Dame was regarded as one of the largest and one of the best educational institutions in America, particularly in the West. The tragic fire helped bring more national attention to Notre Dame. The physical edifices of the “New Notre Dame” indeed were larger, more ornate, and more modern than their predecessors. Main Building and her Golden Dome stand today as a testament to the dreams, ambition, determination, hard work, and faith of our forefathers to build one of the greatest universities in the world.

Sources:

Scholastic

A Dome of Learning by Thomas Schlereth

Edward Sorin by Marvin O’Connell

PNDP 10-AD-02

GFCL 48/17

GNDL 3/52

GNDL 6/16

UNDR 3/06

GTJS 8/02