Various sources, including the Chinese section of the Voice of America, have been carrying speculation concerning the rising prominence of Peng Liyuan (彭麗媛), wife of State Chairman and Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, in the official Chinese media. Miss Peng is Xi’s second wife. When they married in the early 1990s she was a noted entertainer and singer, and continued her own career after marriage, often living apart from her husband. She has been appearing together with him at various state functions. The picture above shows the various foreign grandees attending an import exposition in Shanghai, with Chairman Xi and his wife front and center, no other Chinese leaders featured.

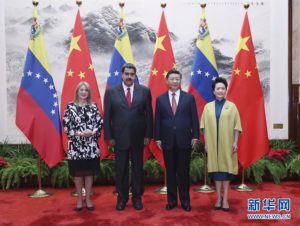

A few weeks earlier Miss Peng and her husband with were photographed together withPresident Maduro of Venezuela, on the occasion of that couple’s state visit a few weeks earlier.

-

President Nicolas Maduro Moros, President of Venezuela, with his wife, Cilia Flores, and PRC State Chairman Xi Jinping and his wife, Peng Liyuan, September 13, 2018

(Xinhua photograph)

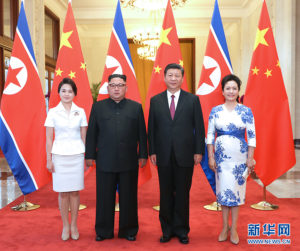

She was also photographed some months before that, again along with her husband, with Korea’s Kim Jong-un and his wife, when that couple were paying a call in Beijing.

-

Ri Sol-ju (Mrs. Kim Jong-un), Kim Jong-un, Xi Jinping, Peng Liyuan (Beijing, June 2018)

In the name list for Kim’s visit, Miss Peng’s name is given priority over those of several Politburo members. The analysis of the protocol of public appearances—who shows up? in what order are they listed?—is a standard technique of “Kremlinology,” one of the ways of seeking to understand what is going on inside closed political systems. It has not been generally the custom in communist systems for a big fuss to be made over the wives of the leaders (there is little or no precedent for adding “husbands” here). When wives are mentioned it is generally an indication that they are political players in their own right. The listing of a leader’s wife, one who has not been publicly active in politics, ahead of a Politburo member is conceivably a big deal.

At this point, the featuring of Miss Peng has more of a social “feel” to it than a political one. On the other hand . . .There is, curiously, a precedent for this from the early 1960s, when China and Indonesia were engaged in a joint campaign against the residues of “imperialism.” On several occasions the official Chinese media featured photographs of Chairman Mao and Liu Shaoqi, then the Chairman (“President”) of the People’s Republic and the second-ranking man in the Party hierarchy, along with their wives, at parties with the Indonesian dictator Sukarno and his wife. At the time this, too, seemed merely social—although highly unusual, in that, as said above, communist leaders generally did not drag their wives along to political meetings.

-

Mao Zedong, Jiang Qing, Wang Guangmei, Dewi Sukarno: Beijing, September 29 1962

During the post-Mao era it did become fairly common for wives of the Great Leaders to accompany their husbands on state visits or in greeting foreign guests, and the most probable explanation for Miss Peng’s appearances simply a continuation of this pattern.

-

Zhuo Lin (Mrs. Deng Xiaoping), Jimmy Carter, Rosalynn Carter, Deng Xiaoping (January, 2019)

-

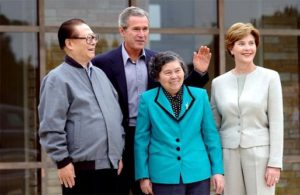

Jiang Zemin, George W. Bush, Wang Yeping (Mrs. Jiang), Laura Bush

But, as it turns out, within a few years after her publicized appearances Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, had emerged as a major political force, so in retrospect the earlier publicity (possibly) acquires some additional significance. With the launching of the Cultural Revolution in 1965-1966, Jiang Qing served as at least the nominal leader and symbol of the most radical Maoists, while Liu Shaoqi was portrayed as a thoroughly evil man, a capitalist roader, a “renegade, traitor, and scab,” Chairman Mao’s inveterate enemy. As Liu’s political position collapsed, his wife, Wang Guangmei, was also exposed to vicious public vilification by Red Guard gangs. Hermain offense, it turns out, was that in the earlier meetings with Sukarno she had shown herself far too stylish and poised (implicitly, one gathers, much more of both than Jiang Qing). And this implies that the political system had devolved into a kind of court politics, with personal rivalries and jealousies becoming as important as differences of political opinion or interest.

The traditional historical attitude, which some nowadays would say was based is that women acquire political power the dynasty is in decay and the state in danger of collapse. Nowadays this sort of thing is dismissed as misogyny, but suppose this if the woman’s position rests, as a necessary if not always sufficient condition, on her relationship with powerful male figures, not to her independent qualities or achievements? The blame is generally ascribed to the emperor’s besotted infatuation with some wife or concubine, a “beauty who shakes the foundation of the state,”—that distracts the emperor from the serious business of governing.

Women have achieved supreme state power in China at least three times. Empress Lü (241-180 BC), wife of the founding emperor of the Han dynasty, took control after her husband’s death, as did Empress Wu (624-705) in the Tang dynasty. Both figure in the histories of the time as viciously cruel women, ruthless in eliminating possible rivals and in imposing their will. Empress Wu is described as sexually promiscuous to boot. The official historians do grant, though, that the reigns of both of these ladies were marked by domestic peace, prosperity, and the fair administration of justice. The Empress Dowager (1835-1908) of the Qing, did not rule in her own name, but was the real power in the state. Her rule is associated mainly with incompetent resistance to the modernizing reforms necessary to saving the dynasty (although some recent historians believe she has been given a raw deal).

To the extent that traditional attitudes retain any currency, then, there is reason to speculate that the prominence accorded to Miss Peng is an omen of trouble, the more so since what prominence Peng Liyuan has derives from the position of her husband (like that of Jiang Qing), rather than any political history of her own. Given the exaltation of Xi Jinping and his leadership to the ludicrous extreme, one can wonder whether this leadership cult is now to be extended to his family. Xi’s supremacy is based not on any charisma or, if it comes to that, any set of talents not shared by his peers, but by accumulating in his person control of the various institutions of power and eliminating any possible rivals. He does not seem to have any particular personal following of his own, apart, perhaps, from the aged Wang Qishan, former head of the Party Disciplinary system, who may be acting as his consigliere (and, significantly, Wang no longer occupies any institutional position of power–he is Vice Chairman (“Vice President”) of the PRC, but no longer has any formal position in the Party hierarchy ). If things go wrong or Xi is seen to make mistakes, he may be vulnerable—and there have been certain signs of resentment of and opposition to Xi. Lacking close political friendships, Xi may be trying to boost the positions of persons he thinks he can trust no matter what: his family.

If it comes to that, there are hints that some potential opposition to Xi may be taking the form of a family feud. In 2018 the Chinese leadership celebrated the 40thanniversary of the “reform and opening movement,” the repudiation of the Cultural Revolution and Maoist radicalism and the adoption of pragmatic economic and social policies aimed at fostering economic growth. The political sponsor of the reforms was, of course, Deng Xiaoping. Xi’s ascendency to power, however, was accompanied by paeans to Xi’s own dad, Xi Zhongxun (1916-2002) and his role in the reform movement (and, if it comes to that, Zhongxun was a rather more liberal reformer than Deng Xiaoping, and much more liberal than his son).

In October of this year, Deng Pufang (鄧撲方), son of Deng Xiaoping, spoke on the reform movement to a meeting of the China Disabled Persons Federation, of which he is chairman. (In 1968, during the period his father was in disgrace, Red Guard thugs threw Pufang out of a third story window, and ever since then he has been a paraplegic. Since his Dad’s rehabilitation he has dedicated his public life to the problems of people with disabilities). The text of the speech has been suppressed by the Chinese authorities, supposedly because it shows hostility to Xi Jinping, but purported transcripts remained available on unofficial sites. The speech does not contain anything explicitly critical of Xi, and toward the beginning even includes the pro forma genuflection to Xi’s brilliant leadership. The speech does imply, without stating, that the current policies, unlike the reforms of the Deng era, are not based on a solid grasp of reality. In describing the reforms themselves, it’s all Deng Xiaoping, Deng Xiaoping, Deng Xiaoping. Supposedly Xi took offense at the glorification of his predecessor, with his own role implicitly being that of a mere continuator and implementer—and, possibly, one who is trying to undo some of the progress Deng had made. A conjecture, then, is that heavy attention to Xi’s predecessors, most notably Deng, is a covert signal of contempt for Xi. This, admittedly, sounds pretty far fetched: but, then, why was the speech suppressed?

All this may be making way too much of a small thing—Mrs. Xi appearing with her husband at public events, being listed among the attended, and having her picture taken. There is so far no indication that she has any political aspirations or exercises any political influence. The most likely interpretation of all of this is that it is simply China adopting the emerging global convention whereby it is normal for world leaders to appear in public with their wives (but, not, perhaps not so curiously, with their husbands—hmm!). But given the attention communist systems have traditionally paid to such name lists and photographs, it is at least worth watching to see whether the new prominence of Peng Liyuan has any significance beyond the banal.