What you will find in Opening Up

Front Plate 8 discusses a leaf of the C-text of Piers Plowman showing a Proud Priest from the unique illustration cycle in MS Douce 104. It provides a facing transcription, paleographical, and literary-historical description, demonstrating the classic Middle English script, Anglicana formata. In this manuscript dated 1427, we can study the close relationship between text and image achieved by its scribe-illustrator. Both illustrated and annotated, this leaf offers a superb instance of how medieval non-linear reading worked. Here the Proud Priest speaks, and the artist portrays him simultaneously in his many roles as a delinquent member of the clergy, a dandified womanizer, and member of Antichrist’s vanguard. The facing transcription includes the prior scene in which the poem’s dreamer is accosted by Elde (Old Age), and left toothless and impotent, in striking contrast to the priest dandy, whose renegade sexual prowess is emphasized by the illustrator. Key aspects of the Opening Up discussion include the manuscript’s dialect, its Middle Hiberno-English translation of Piers, the colonial sensitivities of the Anglo-Irish scribe (who even alters Langland’s text to accommodate them), as well as the decoration and illustration of the manuscript.

What is new in Douce 104 Studies? Scholarship since 2012

Looking at Douce 104 from the standpoint of Ireland’s English manuscripts, John J. Thompson (“Books beyond England”) notes that while the exact purpose for this translation of Piers into a Middle Hiberno-English dialect is as yet unknown, it is clearly an “intelligently illustrated copy of the C text” that was “leaked” and adapted from the “relatively cohesive South-West Midlands dialect.”[1] This speaks to the kind of inter-regional travel of manuscripts we see in Ireland’s colonial diaspora: as Thompson further notes, Douce 104 “may well have absorbed local Hiberno-English iconographical motifs,” adding that “the [scribe’s] current hand based on Anglicana indicates he was presumably better practiced in copying official documents from Westminster or Dublin than transcribing literary material.” The “practically simultaneous production” of the images remains yet another mystery, and the design reveals an “understanding of how major fifteenth-century English centres” decorated their texts, betraying, as Kathleen Scott wrote, “either ‘idiosyncrasy or provincial unease in their execution’.” Thompson’s essay more generally shows the ways in which Anglo-Irish colonial productions regularly crossed ethnic and regional boundaries (see also Front Plate 1 here).[2]

Theresa O’Byrne (“I Yonge scripsit: self-promotion, professional networking, and the Anglo-Irish literary scribe”) has further illuminated the wider Anglo-Irish context of Douce 104 via her extensive work on the vernacular and Latin literary manuscripts and legal documents of the Dublin notary, James Yonge, and his scribal associates, all immediate contemporaries of the Douce 104 artist. As she says of Douce 104’s production team in relation to other known scribal circles in Dublin:

“Research in this area is yet in its infancy and is hampered by the catastrophic loss of historic documents in the 1922 Four Courts explosion and fire. Nonetheless, there are some scribal groups that can be identified and researched further. In 1427, during the lifetimes of all three of the scribes of the Yonge circle, a small group of scribes in the ambit of the Irish exchequer produced an illustrated and annotated manuscript of the C-Text of Langland’s Piers Plowman, now known as Bodleian Douce 104. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton and Denise Despres find compelling parallels between the illustrations and annotations of Douce 104 and a single extant image from the Red Book of the Irish Exchequer, which was lost in 1922. The scribes and illustrators who created these two manuscripts constitute a group of civil servants brought into association by their work for the crown” (“I Yonge scripsit,” 252).[3]

Building upon her prior work tracing the copying of Chaucer, Rolle and other Middle English texts adapted for Anglo-Irish patrons, O’Byrne has illuminated the early fifteenth-century flowering of English culture in Ireland, along with various Latin and French works translated into Middle Hiberno-English dialect.[4] Happily, Irish Gaelic works, too, also flourished in this period under the culturally enlightened leadership of James Butler, Earl of Ormond, and Lieutenant Governor of Ireland, who employed scribes from both Irish cultures, “underscor[ing] the bicultural nature of the Butler family and of the broader community of the Irish marches” (“I Yonge scripsit,” 258). In fact, as O’Byrne shows, Butler awarded Yonge himself a sinecure scribal appointment in the Irish Exchequer between 1420 and 1423 so that he could write Gouernaunce of Prynces for him (250), and this suggests that the Exchequer office was something of a centre of creativity for Middle Hiberno-English texts, in addition to certain Dublin notarial circles she identifies.

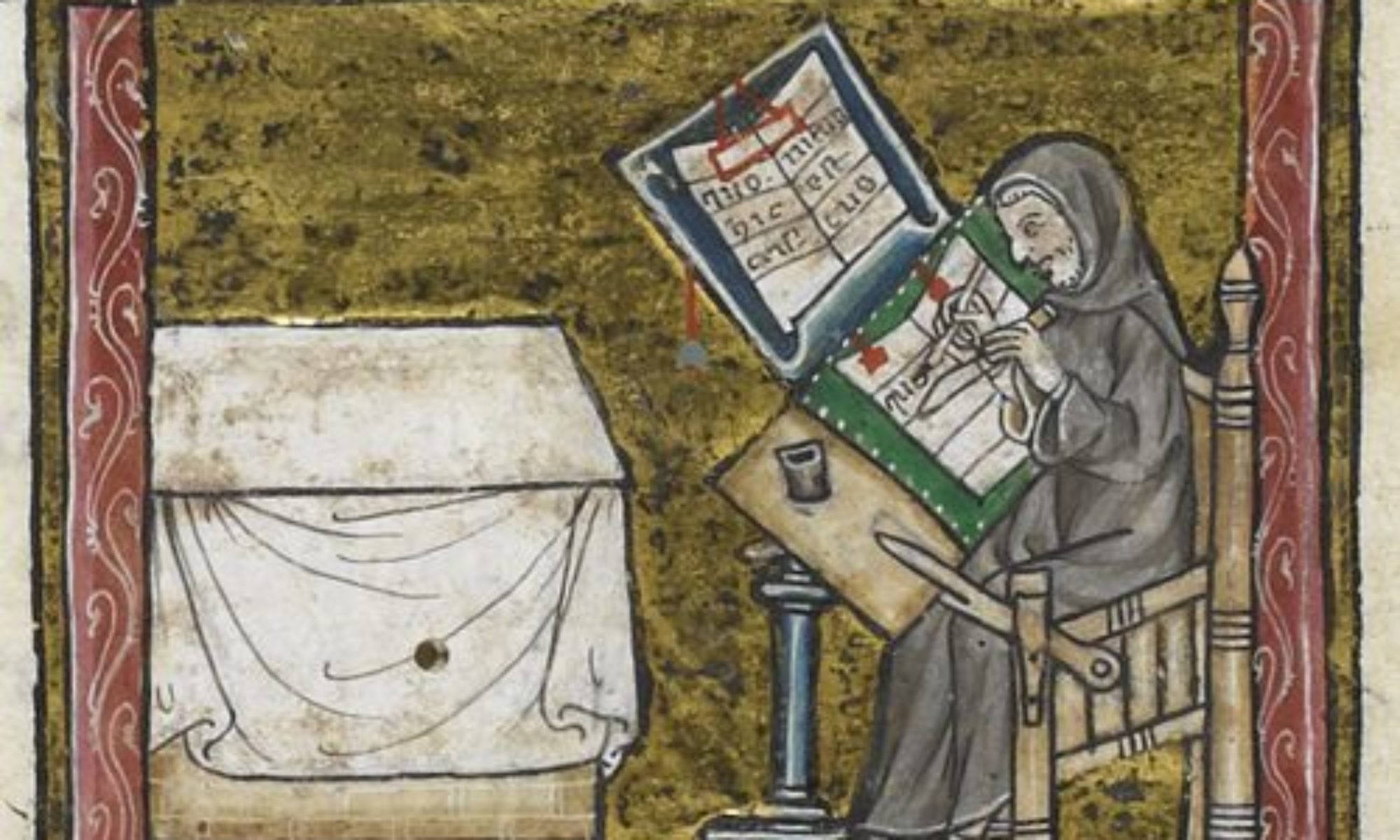

PLACE HERE: FIGURE 1

CAPTION: An image of the Dublin Court of Exchequer at work, from the Red Book of the Exchequer (original destroyed), reproduced from John Gilbert, Facsimiles of the National Manuscripts of Ireland, vol. 3 (London, 1879), plate 37, copy held by University of Notre Dame Library. Anglo-Irish, c. 1420.

The importance of the Dublin Exchequer as the most plausible training centre for the Douce 104 scribe-artist is further discussed in two recent articles by Kathryn Kerby-Fulton. [5]“Competing Archives, Competing Languages” (2015) looks at the Dublin Red Book of the Exchequer fragment in the context of the multilingual Dublin civil service, publishing for the first time since 1879 the colour image of the fragment, and noting the stylistic resemblances between it and the Douce 104 images (both produced in the 1420s). (See Figure 1 above). A second article, “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture of Ireland” (2021) suggests a political connection to James Butler (Earl of Ormond): “the survival of a lone leaf from the Dublin Red Book of the Exchequer, a drawing of the Irish Exchequer at work, is so very like the Douce illustrations in style and satirical spirit, as to suggest shared training, and likely a shared political faction in the Ormond affinity.[6] This fragment offers a rare visual glimpse into civil service satire of the 1420s, showing the participants of the Exchequer court mostly in caricature, excepting the chief recording clerks, and the Chief Baron of the Exchequer…. [Among the barons is] a figure strikingly similar in facial structure to the Sheriff portrayed in Douce 104, while the Chief Baron, his more dignified companion in the bottom left, is facially very similar to Douce 104’s Knight.”[7] The same article also covers the difficulty of connecting the Harley 913 lyrics (see Front Plate 1 above[8]) “with the sudden, largely bureaucratic literary flowering some hundred years later that produced translation projects like the Douce Piers Plowman.” One bridge may be Harley 913’s “Latin ownership inscription to John Lombard of Waterford, who was Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1395.” Since the Red Book fragment shows a contemporary office sketch of the Baron of the Exchequer, it provides us with a type of contemporary “visual ‘portrait’ of the earliest known medieval owner of Harley 913,” a rare connection between these two important periods in medieval Anglo-Irish culture.

Regarding Douce’s “Proud Priest” image itself, in their 2020 essay, Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, Melissa Mayus and Katie Ann-Marie Bugyis (“‘Anticlericalism’, Inter-clerical Polemic and Theological Vernaculars”) reveal the iconographical and polemical context for the Proud Priest among satires on clerical reform and also sober instructional manuals for priests. Although often labeled an “anticlerical” image, the dandified priest appears “all over Latin literature written by clerics for clerics. In fact, this Douce 104 image is an echo of images in works like William of Pagula’s popular manual for priests, the Oculus sacerdotis (Figure 27.2) or James le Palmer’s ecclesiological reformist work, the Omne bonum (Figure 27.3). Both are works aimed entirely at a Latin-literate clerical audience.” As Kerby-Fulton, Mayus and Bugyis show, this image is a marvelous instance of the important difference between anticlericalism and inter-clerical polemic.

Elsewherein the present website Karrie Fuller offers a much more detailed discussion (here) of Douce 104 in the larger context of recent studies of Piers Plowman illustrated manuscripts more generally, including Stephen Shepherd’s ‘Text-Image Articulation in MS Douce 104’. As she notes there, unfortunately, Shepherd misunderstands the distinction between Gaelic-Irish and Anglo-Irish culture,[9] (on this distinction, see Front Plate 1 above), obscuring the dialectal and historical information associating Douce 104 with Anglo-Irish government circles in Dublin. Shepherd, however, rightly echoes Kathleen Scott’s verdict of the Douce artist’s awareness of international norms in his iconography, if not her emphasis on his provincialism.

Bibliographical References

Peter Crooks et al., Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland, “Delving Deeper/ Medieval Exchequer” link: https://virtualtreasury.ie/gold-seams/medieval-exchequer/delving-deeper

Karrie Fuller, ‘Recent Studies on Illustrating Piers Plowman’ (here).

K. Kerby-Fulton, ‘Competing Archives, Competing Languages: Office Vernaculars, Civil Servant Raconteurs, and the Porous Nature of French during Ireland’s Rise of English’, Speculum 90.3 (2015), 674–700.

______________, “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture of Ireland” in Scribal Cultures in Late Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Linne R. Mooney, edited by Margaret Connolly, Holly James-Maddocks & Derek Pearsall (Woodbridge, U.K.: Boydell and Brewer, 2021), 45-64.

K. Kerby-Fulton, Melissa Mayus and Katie Ann-Marie Bugyis, “‘Anticlericalism’, Inter-clerical Polemic and Theological Vernaculars,” Chapter 27 of The Oxford Handbook of Chaucer, ed. Suzanne Conklin Akbari and James Simpson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020) 494-526.

Theresa O’Byrne, ‘Notarial signs and scribal training in the fifteenth century: the case of

James Yonge and Thomas Baghill’, Journal of the Early Book Society, 15 (2012), 305–18.

_____________, ‘Manuscript Production in Dublin: The Scribe of Bodleian e. Museo MS 232 and Longleat MS 29’, New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices: Essays in Honour of Derek Pearsall, ed.K. Kerby-Fulton, J. Thompson and S. Baechle (Notre Dame, 2014), p. 273.

_____________, “I Yonge scripsit: self-promotion, professional networking, and the Anglo-Irish literary scribe,” Medieval Dublin XVII, ed. Sean Duffy (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2019) 237-261.

J. J. Thompson, ‘Books Beyond England’, in The Production of Books in England, 1350–1500, ed. A. Gillespie and D. Wakelin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 259–75.

S. Shepherd, ‘Text-Image Articulation in MS Douce 104’, in ‘Yee? Baw for Bokes’: Essays on Medieval Manuscripts and Poetics, ed. M. Calabrese and S. Shepherd (Los Angeles, 2013), pp. 165–201.

I would like to thank Hannah Zdansky and Theresa O’Byrne for their specialist advice.

[1] Thompson, “Books Beyond England,” 272 for the quotations in this paragraph, unless otherwise noted. On the SWM dialect from which Douce 104 was translated into Middle Hiberno-English, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton and Denise Despres, Iconography and the Professional Reader: The Politics of Book Production in the Douce Piers Plowman (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). On the interchange between these regions, see Thompson’s “Mapping Points West of West Midlands Manuscripts and Texts: Irishness(es) and Middle English Literary Culture,” in Essays in Manuscripts Geography: Vernacular Manuscripts of the English West Midlands, ed. Wendy Scase (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 113–28. Thompson cites Scott from Derek Pearsall and Kathleen Scott, Piers Plowman: A Facsimile of Bodleian Library, Oxford, Douce 104 (Cambridge: Brewer, 1992).

[2] For another important example of manuscript influence across borders, see

H. Zdansky, ‘And fer ouer þe French flod: A Look at Cotton Nero A.x from an International Perspective’, in New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices: Essays in Honour of Derek Pearsall, ed.K. Kerby-Fulton, J. Thompson and S. Baechle (Notre Dame, 2014), pp. 226–50.

[3] O’Byrne’s allusion to the “catastrophic loss of historic documents in the 1922 Four Courts explosion” is now being addressed by a new digital project headed by Peter Crooks, the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland, aimed at using medieval copies of the colonial Irish documents sent back to Westminster as a matter of record keeping. While work on this project is still in progress, the link here provides a guide to the Dublin Exchequer: https://virtualtreasury.ie/gold-seams/medieval-exchequer/delving-deeper

[4] O’Byrne, ‘Manuscript Production in Dublin,” and her “‘Notarial signs.”

[5] First discussed in Kerby-Fulton and Despres, Iconography; and also in “Professional Readers of Langland at Home and Abroad,” Harvard New Directions in Manuscript Studies, ed. Derek Pearsall, for (Cambridge: Brewer, 2000) 101 –137.

[6] Theresa O’Byrne advises me (private communication) that “certainly a circumstantial case can be made for Butler patronage, but there are other possibilities, particularly the Talbots.” We look forward to further research on Douce 104’s origins.

[7] These quotations are from Kerby-Fulton, ““Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture of Ireland,”49-51. See also Kerby-Fulton, ‘Professional Readers’, p. 127, and plates 2d and 2e.

[8] See also K. Kerby-Fulton, “Making the Early Middle Hiberno-English Lyric: Mysteries, Experiments, and Survivals before 1330,” Early Middle English 2.2 (2020) 1-26, which also, like Thompson above, discusses the strong Southwest Midlands settlement pattern, and suggests “that Anglo-Ireland, once it began to acquire more English settlers in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, is partly a literary colony of the Southwest Midlands,” (10).

[9] Shepherd, p. 196 on ‘Irish’ iconography.