(Updates to Ch. 3. V. Two Piers Plowman Manuscripts and the Ushaw Prick of Conscience)

This online supplement to Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts: Literary and Visual Approaches covers publications since its 2012 print publication. See the online Preface for further details. [link “Preface” to Preface; link book title to Cornell Press page]

Background:

Because Piers Plowman manuscripts contain so few illustrations, new scholarship on the subject comes out rarely. Most art historical studies focus on the Anglo-Irish copy found in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 104 as it features the only full cycle of 72 illustrations that accompany the poem, including an historiated initial at its opening. Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 201 (F) also begins with an historiated initial of the dreamer-narrator followed by a few, less formally executed images in its margins. The images in Corpus match the style of those in a copy of the Prick of Conscience copied by the same scribe in Durham, Ushaw College, MS 50. Otherwise, the occasional, informal marginal illustration appears in a handful of Piers manuscripts, and one fifteenth-century depiction of a plowman with oxen prefaces Cambridge, Trinity College MS R.3.14 (Hilmo, Op.Up, 189). Though few in number, the extant images provide insight into how a handful of bookmakers and readers responded to the text, drawing upon longstanding traditions of iconography and adapting them to the challenge of illustrating a complex allegorical narrative. No fancy presentation copies on par with Ellesmere’s Canterbury Tales or Thomas Hoccleve’s illuminated copies of the Regement of Princes survive, but the more casual pictorial responses to Piers are no less intellectual or interpretative in content. Hilmo points out Langland’s condemnation of “ostentatious” art, particularly in Lady Mede’s agreement to display donor art in her friar-confessor’s church (Schmidt, B text, 3.47-75), even as he incorporates elements of “visual iconography” into the poem elsewhere. Perhaps Langland’s treatment of iconography influences the artistic register employed in images that emphasize content over flashiness. Sometimes these visual responses encroach upon the text block (as opposed to lingering wholly in the margins) so that they become “one symbol system extending another” (Hilmo, Op. Up, 189-90). This observation rings true in the opening historiated initials of Douce and Corpus in which portraits of the narrator-author sit comfortably and literally inside the text.

Updates to 3.V.1. Animating the Letter and Visually Authorizing the Text in the CCCO MS 201 (F) and the MS Douce 104 Manuscripts of Piers Plowman

Although there continues to be limited discussion of the two historiated initials that open Corpus and Douce, they essentially function as author portraits, and recent work on such images in vernacular manuscripts can further enlighten our understanding of these initials. Hilmo first introduces the connection between these images and a longstanding tradition of author portraiture descending from early depictions of the four evangelists (Op. Up, 190). The two Piers initials present rather more complicated visualizations resulting from their conflation of the narrator and author in keeping with the poem’s own lack of distinction between the two. Instead of depicting an actual historical person, such as those images of Chaucer and Hoccleve found in the two earliest manuscripts of Hoccleve’s Regement, the Piers portraits portray a more abstruse narrator-author figure. In Corpus and Douce, therefore, the author-dreamer portraits erase the distance between author and text because the voice behind the poem is also the voice of the poem, an active character within the narrative. The figure in Corpus in particular depicts a sleeping man with additional features pulled straight from the Prologue itself, unambiguously the poem’s dreaming speaker. Douce poses greater challenges since its damaged image makes it difficult to see what the narrator-author figure holds in his hands. Nevertheless, because these images draw from this tradition, it is worth examining them further within this larger historical context.

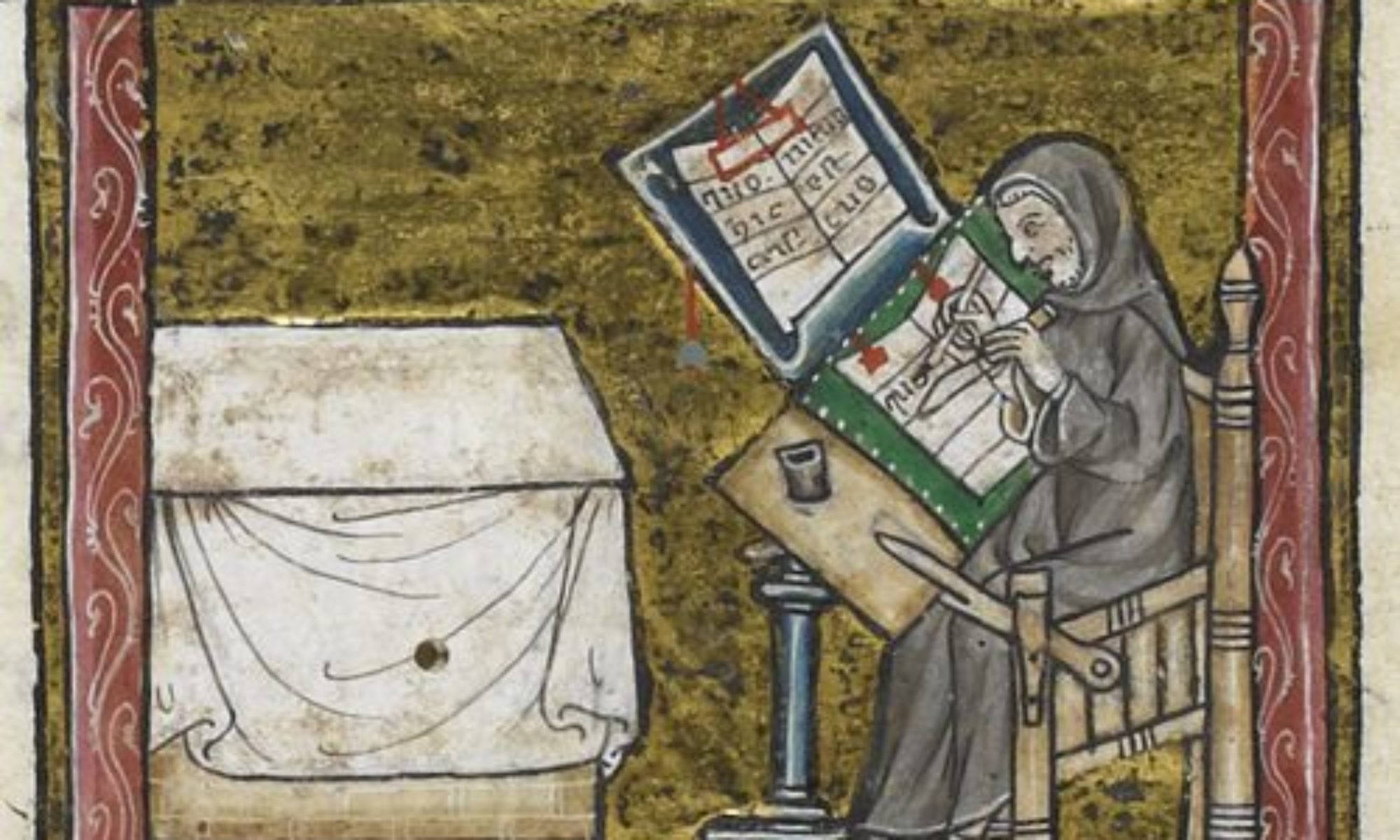

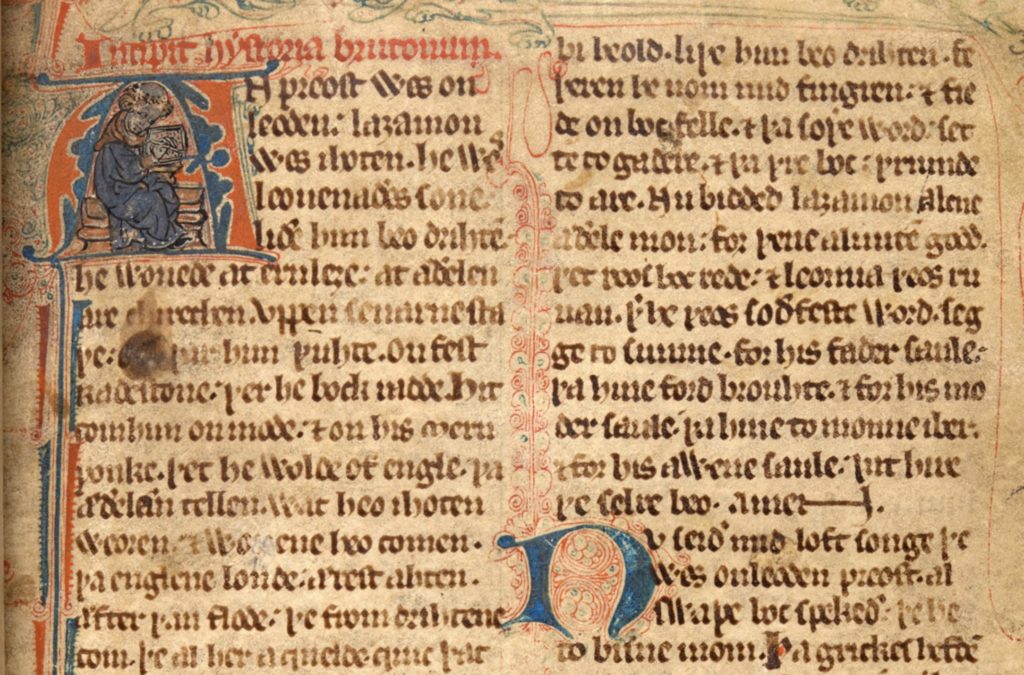

For contextualization, two key studies published since 2012 by Sonja Drimmer and Elizabeth Kempf provide valuable resources on late-medieval author portraits in Middle English books. After outlining the earlier history of author portraits originating in sacred texts, Drimmer argues that author portraits begin to change in the mid-thirteenth century as distinctions between authors, translators, and scribes blur. Artists increasingly incorporate vernacular conceptions of authorship based on an intertextual “theory of creativity” that “was one founded upon complex, varied and systematized assimilation of pre-existing material–in other words, the production of modified copies” (Drimmer, 101). In other words, late-medieval illustrators drew from a longstanding, largely Latinate portraiture tradition, but adapted it over time and in individual contexts by incorporating visual elements meant to reflect the vernacular author’s conceptualizations of their labor. Drimmer, expanding upon Maidie Hilmo’s 2004 discussion of the first surviving portrait of an English poet, identifies the transition to later author portraiture in the thirteenth-century depiction of Laȝamon writing the Brut in London, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A.ix, which mimics the architectural, ecclesiastical framing of the writer with a small but significant shift in his posture and the position of his pen on the page (for Hilmo’s earlier discussion, see Medieval Images, 106-112). What distinguishes this earliest of vernacular examples from depictions of the Gospel writers “is that it announces the present writer’s responsibility for the book at hand and his physical relationship to it” (Drimmer, 89).

In the case of the Corpus Piers, the influence of contemporary trends in author portraiture manifests in its reinvention of the space represented inside the initial A and its visualization of dreaming as a form of authorship popularized by the vernacular dream vision genre. Hence the initial shows a man in the act of dreaming rather than the physical act of writing with a pen on parchment. Rather than depicting an indoor, ecclesiastical space as in the earliest author portraits, Corpus moves the narrator-author outdoors in keeping with the poem’s setting. However, the gold background, a mainstay of religious iconography, retains something of a sacred feel to the place, while also placing the man in “another dimension that fits in with the world of his dream” (Hilmo, Op.Up, 190). Moreover, while the frame constructed by the letter A appears less explicitly architectural than some earlier examples, the tower-like structure (possibly Truth’s tower from the Prologue) that functions as the dreamer’s footstool replaces some of the symbolic value formerly represented by ecclesiastical spaces, although as Stephen Shepherd points out, the stool could also be a hopper used for sowing seeds (Shepherd, 194). The image’s ambiguity allows for multiple interpretations simultaneously, enriching its meaning and its relation to the text, and denying one possibility in favor of another does no justice to its multivalent potential for rich readings.

Both Drimmer and Kempf reiterate their point that late-medieval illustrators incorporate vernacular conceptions of authorship into author portraits. They both discuss examples of actual historical authors shown with their books; however, the dreamer figures in the Piers manuscripts emphasize instead the poem’s vernacular genre, a form typified by works such as Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls or Book of the Duchess, in which dreaming functions as a hermeneutic method of composition that enables the dreamer to digest or process difficult waking or reading experiences. In dream visions, a popular Middle English genre inherited from Latin ancestors, such author-narrators can explore deep philosophical and theological questions in ways unavailable to the awake person. While examining the portraits of Chaucer and Hoccleve in the two earliest copies of Hoccleve’s Regement, Kempf stresses the point that “author portraits can be studied in respect of the conceptions of authorship they display” and that through their image-text relationship “they demonstrate that medieval authors, scribes and illuminators were not only aware of the semantic possibilities granted by an interplay between different media, but that they made strategic use of such visual-verbal means for a variety of purposes” (155, 109). Moreover, Deborah McGrady demonstrates how Christine de Pizan’s author portraits rely on her reading skills to authorize her writings, which, in combination with the examples discussed by Drimmer and Kempf, reveal the diversity of vernacular conceptions of authorship on display in this popular art form. In Piers, the narrator-author’s act of composition occurs within the narrative itself as the dream unfolds, and the Corpus portrait announces this crucial textual feature at the outset, which, as it happens, reinforces the rubricator’s emphasis on the poem’s many voices as discussed by Noelle Phillips. These factors go hand in hand with the Corpus redactor’s “detailed engagement with the poem, its content and form” in a manner indicative of a secular clergy member perhaps catering to a lay audience (Horobin, 22). Inasmuch as the illustration works to establish Corpus’ unique poetic voice, these newer studies reinforce James Weldon’s identification in the 1990s and Hilmo’s 2012 elaboration on the strong connection between Corpus’ redacted Prologue and the portrait’s incorporation of textual details within it. The portrait, the rubrication, and all the quirky variants and unique lines made by the Corpus redactor, therefore, come together in the manuscript’s presentation of Piers to create a singular version found nowhere else in the manuscript tradition.

In contrast to Corpus’s dreaming figure, the portrait in Douce is badly damaged, making it difficult to see and, therefore, interpret. The most recent discussion of this narrator-author by Stephen Shepherd builds on Kathleen Scott’s earlier identification of the image’s “unidentifiable” representation of an “agricultural implement” (Scott ,18). He views the image in conjunction with Corpus as a representation of agricultural labor concerned “less with the localizing details of the opening lines than with the universalizing and visionary-apocalyptic dimensions of allegorized labor” (196). Shepherd sees the dreamer figure as holding an agricultural tool called a billhook, an implement Langland never mentions, and reads its text-image relation as a portrait showing “a laborer typology underwritten by a national (and for Douce not peculiarly Irish) readership” (196). The image need not be “peculiarly Irish” in order for it to cater to an Anglo-Irish audience (as opposed to a Gaelic-Irish one), nor does its every feature need to aim explicitly at that objective in the first place, especially if Corpus and Douce together intimate the presence of “a coherent exegetical tradition” for Piers with an international reach (196). The difficulty here, as detailed in Kerby-Fulton’s and Despres’s monograph on Douce, stems from the complex relationships between the English, Anglo-Irish, and Gaelic-Irish cultures with their porous boundaries affected by ongoing cross-cultural exchange periodically interrupted by legislation attempting to regulate, or altogether stop, that process (Iconography). Nevertheless, Shepherd’s argument about the dreamer image carries weight if the object in the dreamer’s hand is a billhook (or, presumably, any other agricultural tool), a real possibility, to be sure, but no current consensus on this issue exists. Even if the illustrator is not bogged down by “localizing details” or, for that matter, narrative facts, a more explicit explanation about why the illustrator chooses to place a billhook instead of the “pyk-staff,” or pickaxe, Piers uses in C.8.64 into the hands of a dreamer who never himself labors physically in the first vision’s field of agricultural allegory would help (Shepherd 195-6).

While Shepherd’s billhook connects the portrait to the poem’s prominent agricultural themes, Hilmo suggests a harp, evoking a minstrel-narrator persona reminiscent of Irish iconography, and several other proposals that Hilmo acknowledges as reasonable, such as a pilgrim’s staff, have been made (Op. Up, 193-5). The harp, intimated by the shape of the Y itself, draws upon iconographical traditions of David, figuring him as God’s own minstrel, sometimes with hand placement in a similar position as the Douce 104 dreamer’s (for comparison, see images of David in Op. Up, 195). A musical instrument would imbue sound with an authorizing function as the dreamer inside the “Y,” or I, signals his role as the poem’s voice. Despite disagreements over the exact gold-colored object in the dreamer’s hands, there is a general consensus about the special importance of this portrait, which, unlike the manuscript’s other illustrations, the scribe preplanned. Perhaps new digital imaging tools could help shed light on the situation, but until more information about the object in the dreamer’s hand comes to light, multiple possibilities remain valid. Until that time of greater clarity arrives, maybe, for today’s reader of the ambivalent figure, the image’s potential for expressing multivalence could be read as valuable in itself, more important even than being “right” about what it depicts.

Shepherd also concludes, based on comparisons with another illustrator, John Siferwas, that the Douce illustrator might be “someone who knows the intellectual culture of the highest of high-end book illustration,” an artistic influence worth considering in this less than high-end production (198). Indeed, Kathleen Scott’s earlier work connects the dreamer portraits in both Douce and Corpus to “the larger arena of continental illustration” (19). She also points out that Douce’s “secondary decoration,” likely the work of the main illustrator, shows an artist who “understood how conventional borders and initials were designed in major fifteenth-century centers of book production” (Scott, 13-14). Since the scribe-illustrator worked as an Anglo-Irish civil servant, he could have connections to London and, therefore, contact with its luxury book industry. At least as important, though, would have been his access to iconography in non-luxury productions, especially those “cheaper” images popping up in Middle English manuscripts beginning in the later fourteenth-century, such as, most notably, the Gawain-manuscript (British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.X). However, the specific image samples the Douce artist knew remain unknown.

As visualizations of the dreamer, both the Corpus and Douce images prioritize the act of narrating and the performance of dream composition over an historically accurate representation of the real-life author. This priority provides some insight into the illustrator’s interpretation of the text even as it sets up Corpus’s readers to experience the text from the illustrator’s perspective at its crucial opening moment.

Updates to 3.V.2. The Roles of the Scribe in the Decorative Scheme of the CCCO MS 201 Piers Plowman and the Ushaw Prick of Conscience

Hilmo’s discussion of the Corpus scribe’s concluding stork drawing or of the decorative scribal doodles, or cadels, in the upper margins of Corpus and the Ushaw Prick of Conscience, a manuscript copied by the same scribe, has received no follow-up discussion. However, in terms of Corpus, Hilmo’s point that the cadels respond to Conscience, a topic on the scribe’s mind after his work on the Prick of Conscience, supports Phillips’ observation that Conscience ranks at the very top among the rubricator’s most rubricated words, a point made especially intriguing in the likely situation that the scribe and rubricator are the same person (448). I found no recent discussion of the Ushaw manuscript on its own or in relation to Corpus. Such doodles, though, often go unnoticed or are disregarded as unimportant. But, given their potential to serve as reader responses, they deserve greater attention because they provide evidence for understanding a text’s reception history, and Piers manuscripts still remain largely unexplored on this front. Even when marginal drawings lack a special relationship with the text, they indicate something of a book’s history, whether about its early uses, ownership, scribal ticks, or any information that affects our understanding of a book’s final material form.

Karrie Fuller, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

Bibliography:

Adams, Robert, et al., eds. Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, Vol.1: Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 201 (F). The Society for Early English and Norse Electronic Texts. Republished 2014. Accessed November, 7, 2019. http://piers.chass.ncsu.edu/texts/F.

Drimmer, Sonja. “Visualizing Intertextuality: Conflating Forms of Creativity in Late Medieval ‘Author Portraits.’” In Citation, Intertextuality and Memory in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Vol. 2, ed. by Yolanda Plumley and Giuliano di Bacco, 82-101. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.

Gasse, Rosanne. The Feral Piers: A Reader’s Experience of the British Library Cotton Caligula A. XI Manuscript of Piers Plowman. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2016.

Hilmo, Maidie. Medieval Images, Icons, and Illustrated English Literary Texts: From the Ruthwell Cross to the Ellesmere Chaucer. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

Horobin, Simon. “Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 201 and its Copy of Piers Plowman.” In Middle English Texts in Transition: A Festschrift Dedicated to Toshiyuki Takamiya on his 70th Birthday, ed. by Simon Horobin and Linne Mooney, 21-39. Boydell & Brewer: York Medieval Press: 2014.

Kempf, Elizabeth. “‘Of his persone, I have here his liknesse Do make’: Mediality and Conceptions of Authorship in the Regement of Princes.” In Performing Manuscript Culture: Poetry, Materiality, and Authorship in Thomas Hoccleve’s Regiment of Princes,138-158. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn and Denise L. Despres. Iconography and the Professional Reader: The Politics of Book Production in the Douce Piers Plowman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

McGrady, Deborah. “Reading for Authority: Portraits of Christine de Pizan and her Readers.” In Author, Reader, Book: Medieval Authorship in Theory and Practice, ed. by Stephen Partridge and Erik Kwakkel, 154-77. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

Pearsall, Derek and Kathleen Scott. Piers Plowman: A Facsimile of Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Douce 104. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1992.

Phillips, Noelle. “Seeing Red: Reading Rubrication in Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 201’s Piers Plowman.” The Chaucer Review 47, no. 4 (2013): 439-464.

Schmidt, A.V.C., ed. Piers Plowman: A Parallel-Text Edition of the A, B, C, and Z Versions, Rev. ed., 2 vols. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2011.

Scott, Kathleen. “The Illustrations of Piers Plowman in Bodleian Library MS. Douce 104.” Yearbook of Langland Studies 40 (1990): 1-86.

Shepherd, Stephen H.A. “Text-Image Articulation in MS Douce 104.” In ‘Yee? Baw for Bokes’: Essays on Medieval Manuscripts and Poetics, ed. by Michael Calabrese and Stephen H.A. Shepherd, 165-201. Los Angeles: Marymount Institute Press, 2013.

Weldon, James. “Ordinatio and Genre in MS CCC 201: A Mediaeval Reading of the B-text of Piers Plowman.” Florilegium 12 (1993): 159-175.

Additional Online Resources:

Images of illustrations in Douce 104: http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/msdouce104.htm And https://medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/catalog/manuscript_4483

Digitized MS, CCCO MS 210: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/inquire/Discover/Search/#/?p=c+0,t+,rsrs+0,rsps+10,fa+,so+ox%3Asort%5Easc,scids+,pid+bbe3f34b-ebe3-4757-b2e0-cd4268c6749e,vi+bb545305-2b2b-43e2-904f-576eb9719ea0

(on author portraits) https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/power_piety/

Updated URLs:

Footnote 135. Image of plowman in Cambridge, Trinity College MS R.3.14 at PPEA: http://www3.isrl.illinois.edu/~unsworth/cyber-mla.2002/SNAG-0018.jpg (no good) But it is pictured here: https://sites.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/2016/03/31/reading-the-z-text-of-piers-plowman/

Ftnte 139. http://www.galbithink.org/sense-s5.htm (link still good)

Ftnte 152. Harley 1808, fol. 9v: link broken http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&I11ID=19679

New link: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=19681

Ftnte 174. (link still good) http://www.abdn.ac.uk/stalbanspsalter/english/commentary/page072.shtml

Ftnte 175. http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/results.asp (incorrect link published) correct link: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=52230

Ftnte 176. Stowe 944 (link broken) http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=5353 (new link): https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=12225

Ftnte 177. (link still works) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:British_Library_Additional_37049_47v_Pride.png

Ftnte 184. (link still works) http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/frame12.html