Welcome to the Re-Opening Up Digital Companion, a guide to new developments since the 2012 publication ofOpening Up Middle English Manuscripts: Literary and Visual Approaches. This guide covers relevant publications 2012 -2023.

The Front Plates of Opening Up and More Ways of Using Them: Literary Texts Chosen for their Paleographical, Textual, and Thematic Vitality

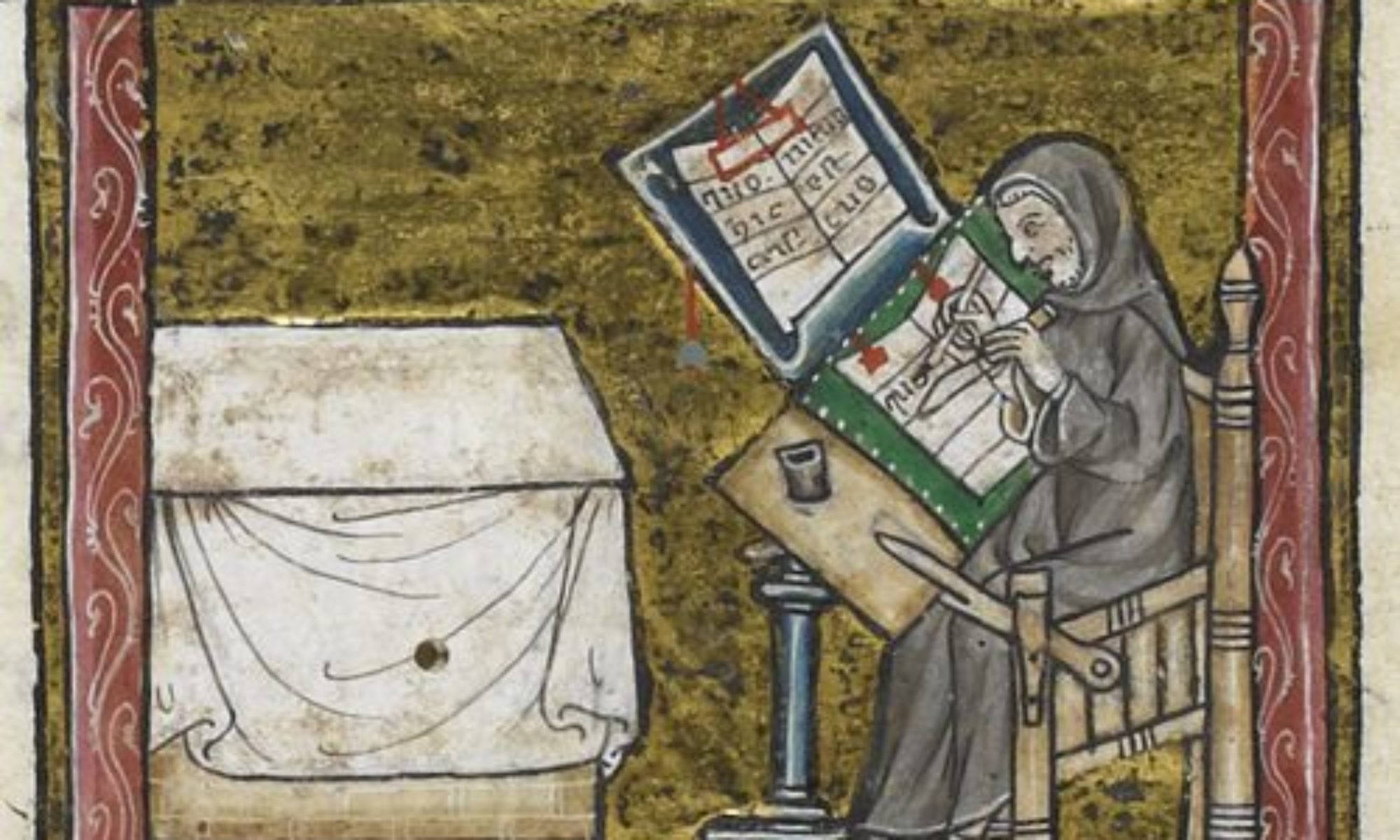

First and foremost, the Front Plates demonstrate all of the major kinds of scripts that a student reading Middle English after 1275 might meet, and offering a chance to learn and practice transcription skills. But these Front Plates were also specifically chosen because they exemplified classic moments in literary and textual history: take, for instance, annotation by the earliest known scribe of Chaucer (Scribe B/ Adam Pinkhurst) writes at the end of the unfinished “Cook’s Tale”: “Of this Cokes tale maked Chaucer na moore” (Front Plate 4). Other Front Plates exemplify intriguing problems in medieval reading habits: for instance, can we tell by looking at a prohibited Wycliffite tract in manuscript (Front Plate 6) whether the text was copied to be performed out loud or read silently? The Plates also exemplify scribal identities and writing practices: for example, can we tell whether a text was copied by a woman or not (Findern MS, Front Plate 9)? The Front Plates especially support modern literary analysis: for example, do the tail rhyme markers and key words the scribe emphasized in the play Wisdom reveal how it was performed by actors (Front Plate 10)? Elsewhere, we can find markers of colonial experience and ethnicity in, for instance, the anti-Irish imagery of the Douce Piers Plowman (Front Plate 8); alternatively, we find evidence of creative cultural hybridity in the rollicing early Anglo-Irish parody, “Land of Cockaygne.”

Since Opening Up was published in 2012, even more ways of using the Front Plates in the book have emerged. Here are some key ideas for practical use and discussion of the Front Plates (extra Bibliography since 2012 can be found here on this companion website, Re-Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts):

- Paratexts, Non-Linear Reading, and Medieval Reading Practices: see for instance Front Plate 8 from the illustrated and annotated Piers Plowman in MS Douce 104.

- Meditation, Memory, and Cognition: see for instance the decoration, rubrication and border treatments of The Pricke of Conscience (Front Plate 3).

- Formalism and Performance: see for example the heavily punctuated Wycliffite text, Omnis plantacio (Front Plate 6), and the play Wisdom (Front Plate 10).

- Crossing Borders, Colonial Experiences, and Ethnic Tensions: see the Anglo-Irish satire, “Land of Cockaygne,” (Front Plate 1) and Piers Plowman, MS Douce 104 (Front Plate 8).

- Multilingual Reading Experience: see for instance the scribe’s difficulties in transitioning from Latin to English in the lyric “Ihesu swete” (Front Plate 2) or the strategic mix of Middle English, French and Latin in Hoccleve’s autograph, Huntington Library, MS 111 (Front Plate 7).

- Gender: When Women Scribes Wrote: see for instance Sir Degrevant (Findern MS, Front Plate 9), a romance copied by a woman scribe.

- Textual History, Editorial Challenges, and Literary Analysis: see for instance Chaucer’s two earliest known scribes wrestling with the abrupt ending of “The Cook’s Tale” (Front Plates 4 and 5).

In the guide below, these themes, where relevant, are highlighted in blue. Live links to online digitized manuscripts have also been added.