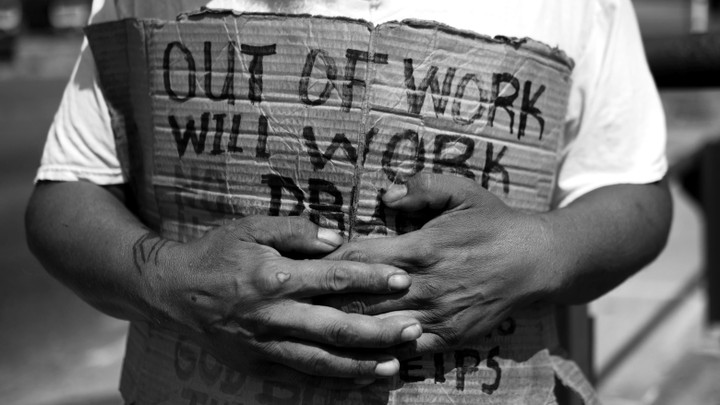

This pandemic will be especially punishing for low-income workers, just as they were starting to reverse a generation of widening inequality.

Nobody should confuse 2020 for the height of the 20th-century Progressive era, but the past few years saw precious gains for poorer workers. In late 2019, wages in low-income industries were growing faster than at any time in the previous 20 years. This achievement was the result of minimum-wage hikes across the country (a huge win for labor groups, whose goals once seemed impossible) and historically low unemployment. The U.S. economy had added jobs for more than 100 consecutive months, the longest streak on record, bringing the unemployment rate for black and Latino workers down to its lowest in U.S. history. The federal safety net was, arguably, as strong as it had been in half a century, thanks to the passage of the Affordable Care Act. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s December 2019 report on household income, federal tax-and-transfer policy was doing more to reduce income inequality than at any other time on record, going back to at least 1979.

The coronavirus pandemic is poised to halt this progressive momentum. According to the White House, unemployment could hit 20 percent in the next few months. That means the virus may swing the economy from the lowest unemployment rate since the 1950s to the highest rate since the 1930s. According to JP Morgan analysts, GDP could decline in the second quarter by 14 percent. If they’re right, the economy will lurch from the longest expansion on record to the worst quarterly GDP decline on record.

Ground zero for the pandemic’s threat to the labor force are the face-to-face services and leisure economy, much of which have been forcibly shut down by governments to prevent the spread of the virus. Online reservations for restaurants in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., have declined to zero. The largest hotel in New York City, the Hilton Midtown on Sixth Avenue, is closing its 1,878 rooms indefinitely, for the first time ever. Disneyland is empty, and the casinos that had always lit the Las Vegas strip have gone dark.

The workers in these sectors—salespeople, waiters, hotel desk clerks, groundskeepers, maids, and entertainment attendants—have a few things in common: First, their average annual wages are less than $30,000, including tips, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (The typical annual wage for a full-time worker in the U.S. is about $47,000.) Second, they have the fewest labor protections, such as paid sick leave, and in many cases their tips don’t count as income when they apply for unemployment insurance. Third, they can’t do their work from home. Remote work is the labor market’s only remedy against the virus while Americans are in mass lockdown.

There is still so much we don’t know, including exactly how many people will lose their jobs in the next few months. Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, has said that 18 percent of the labor force is at “high-risk”—more than 25 million jobs. That might sound extreme, but a recent NPR/PBS poll found that by March 14, exactly 18 percent of respondents said they had already been let go or had their hours reduced. For Americans making less than $50,000, the number spiked to 25 percent.

What seems more certain is that the effects of the pandemic will remain with the U.S. for generations. It may supercharge inequality in the short term. Eventually, however, the pandemic may give birth to a new kind of socialized thinking in America that demands universal insurance and sick leave for all, not just the white-collar remote-work class. For example, Muro believes that national paid leave, if it becomes law, will likely be expanded, because offering paid leave to coronavirus patients in 2020 only to yank it away from cancer patients in 2021 would be too incongruous.

When the 1918 influenza pandemic returned for its second and third waves, it didn’t target low-income workers anymore. It simply killed everyone—laborers and bosses, men and women. In the long run, a virus does not discriminate between the rich and the poor. At some point, then, the question must be asked of America’s political leaders: Why do we?