The subject line for the email was “Fwd: Fun Opportunity for Medievalists!” For a curious cat like me, that’s catnip. I want fun! I’m a medievalist! Whatever could this opportunity be? Clearly, the subject line grabbed my attention, which was waning over the course of that particular April afternoon after hours of poring over my own writing.

I immediately opened the email, which Christopher (Chris) Fletcher (Assistant Director of the Center for Renaissance Studies, Newberry Library) had written to be circulated to the medievalists at the University of Notre Dame. Chris shared news of a workshop taking place at the Newberry Library in early June 2025 called “Cartooning the Medieval.” See for yourself how Chris pitched the workshop:

This is going to be a very exciting event where scholars will have the opportunity to work with and learn from professional cartoonists and graphic artists, in the hopes that this collaboration will help them imagine ways to make their work more engaging, exciting, and valuable to audiences outside academia. In particular, medievalists who join us will get to learn from my co-organizer, Kristen Haas Curtis, how to be cartoonists themselves!

I could not pass up the opportunity to participate. Though I don’t currently work with cartoons, comics, zines, and other graphic media in my research, I have taught graphic novels like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Art Spiegelman’s Maus in the past. I wanted to dive deeper into this visual world of fascinating interpretive and representational possibilities, and the chance to have it tie-in with my medieval interests was too good to pass up. The nod to audiences outside of academia also intrigued me since my time at Notre Dame has centered on public humanities and outreach. What use is what we do if it’s all sequestered in the ivory tower?

Early June arrived, and I made the short journey from South Bend, IN to Chicago, IL. Chris and Kristen gave us all instructions to arrive early in the morning for registration in addition to coffee and doughnuts. I navigated to the Newberry Library’s Ruggles Hall. Large windows welcomed in ample light and gave us a view of Washington Square Park. A staff member greeted me and the other participants. There were two different name tags: ones with red borders (for the medievalists) and others with blue borders (for the cartoonists). I took a red bordered name tag and wrote my name and preferred pronouns on it. In the spirit of the event, I decided to draw a cat in one of the corners—but not just any cat! No, I was at a rare gathering of cartoonists and medievalists. I decided to give my cat a sword because, well, that was the only medieval accessory I could think of (and draw) at the time. My lack of drawing skills were immediately apparent, but I was willing to try.

I saw a familiar face: that of my colleague Elizabeth (Liz) Hebbard, Assistant Professor in the Department of French and Italian at Indiana University Bloomington. We had no idea that the other would be there, so it was a pleasant surprise to see a fellow French medievalist among the crowd. She pointed out a long table at the far side of the room. There were zines, stickers, and even printed out academic articles carefully laid out on it. This was a space for us to swap the fruits of our labor. The cartoonists were prepared and had numerous materials to share. Liz, for her part, had sewn numerous chickens, which one of the cartoonists believed to be neat little fabric coasts. When I asked Liz about it, she smiled and explained that sewing the chickens was a great pedagogical tool in her classrooms. Sadly, I can’t remember everything she said about it all (I should have been taking notes!), but if you’d like to learn more then you’d have to ask her yourself. Anyway, I snapped a quick picture of the table and tried to get out of everyone’s way as they pored over the precious items.

Before I knew it, Chris and Kristen instructed us all to take a seat and settle in for the day. They projected the schedule on the screen. While we would start the day together, there would be a point when the medievalists and cartoonists—who outnumbered the medievalists!—would go their separate ways to learn more about the workings of the other group. Later in the day, we’d all work together and combine our skills and newfound appreciation for one another’s areas of expertise.

After we got oriented, we immediately plunged into a rather involved icebreaker activity. Medievalists and cartoonists alike had to circulate throughout the large room, break into groups, and answer questions that Chris and Kristen had devised. With every question that popped up on the screen we had to find a new conversational group. Since there were more cartoonists than medievalists, I often found myself being the lone medievalist chatting with two to three cartoonists. At first, I felt intimidated; these people were professionals with a particularly cool skillset! Not only were they incredible artists, but they also thought deeply about how to craft and present a narrative. They knew how to tell stories and connect with people on various levels: visually, emotionally, and more. In comparison, my academic skillset felt too narrow, too bookish, too esoteric. But I quickly found out that we had plenty of overlapping interests, especially when it came to questions about representation. How do we responsibly tell stories? Who do we keep in mind when we present our work? What are the overarching stakes? The time allotted for the icebreaker activity passed quickly, and I found myself wanting to continue all the exciting conversations.

Chris and Kristen gave us all a short break before dividing us into groups. Kristen rounded up the medievalists and led us down to a conference room. We found seats along a long table and all faced the screen like dutiful students. Kristen was going to teach us a thing or two about cartooning! Some of my medievalist peers were antsy; they knew that the cartoonists were getting a crash course in medieval studies with Chris. This meant looking at some of the Newberry’s collections, and my fellow medievalists wanted to take a peek at those materials. They’d have to wait though! As I took my seat, I noticed an array of materials on the table: various pens, scissors, and some worksheets. We’d be doing some cartooning of our own!

Kristen did a fabulous job getting us to embrace cartooning. She encouraged us to take as little time as possible to draw — when it comes to cartoons, perhaps simpler is better! We came up with cartoon versions of ourselves that were inspired in large part by Kristen’s own cartoon-self. She pointed out her cartoon-self’s hair: not quite as detailed as her own hair but a distinguishing feature nonetheless that makes her cartoon, well, her. Once our creative juices were flowing, Kristen taught us some cartooning terms and taught us how to make our own zine using just a sheet of paper and a pair of scissors. Ever the prepared teacher, she shared her own zines as examples. The possibilities seemed endless!

I particularly enjoyed how Kristen emphasized cartooning and making zines as great media for communicating with medievalists and non-medievalists alike. She wanted us to feel empowered to share visually the crux of our research in ways that were fun and approachable. One of the zines she made and shared with us laid out her research in such a vibrant manner: her cartoon-self got to interact with Chaucer and the various iterations of the wife of Bath that have sprung forth from adaptations of The Canterbury Tales. Who said discussions about research had to be stuffy and adhere to any particular scripts/modes of communication?

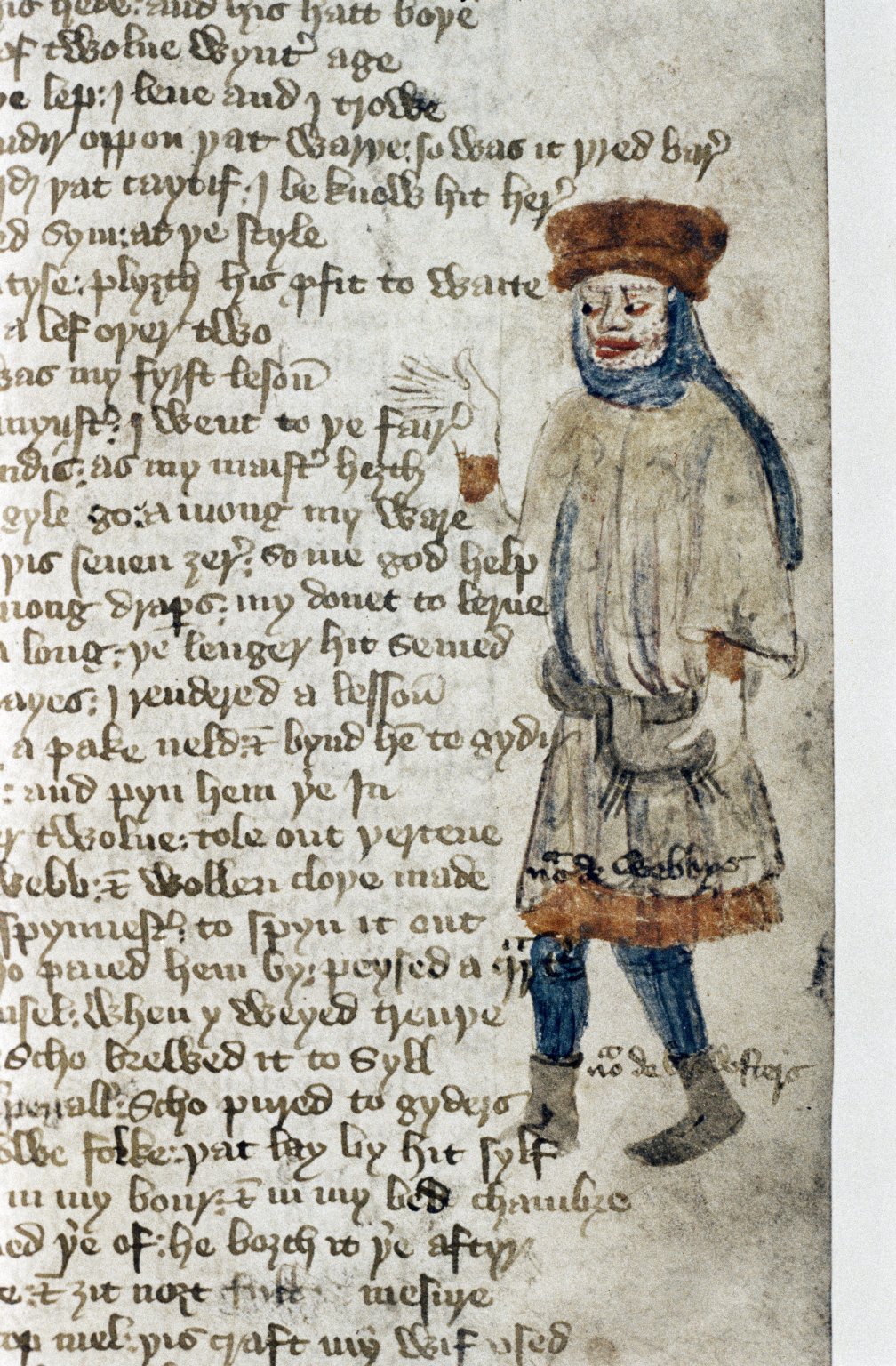

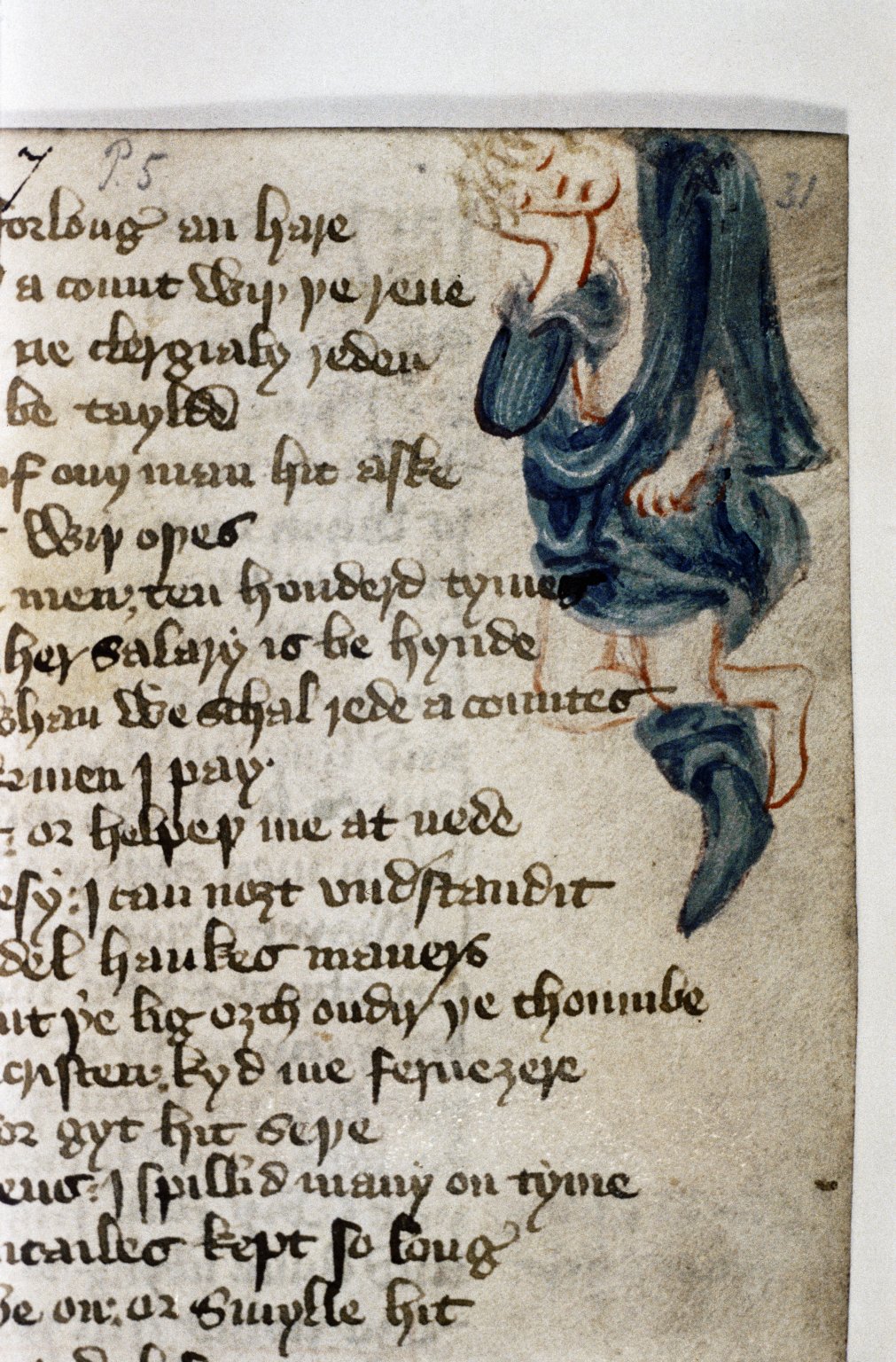

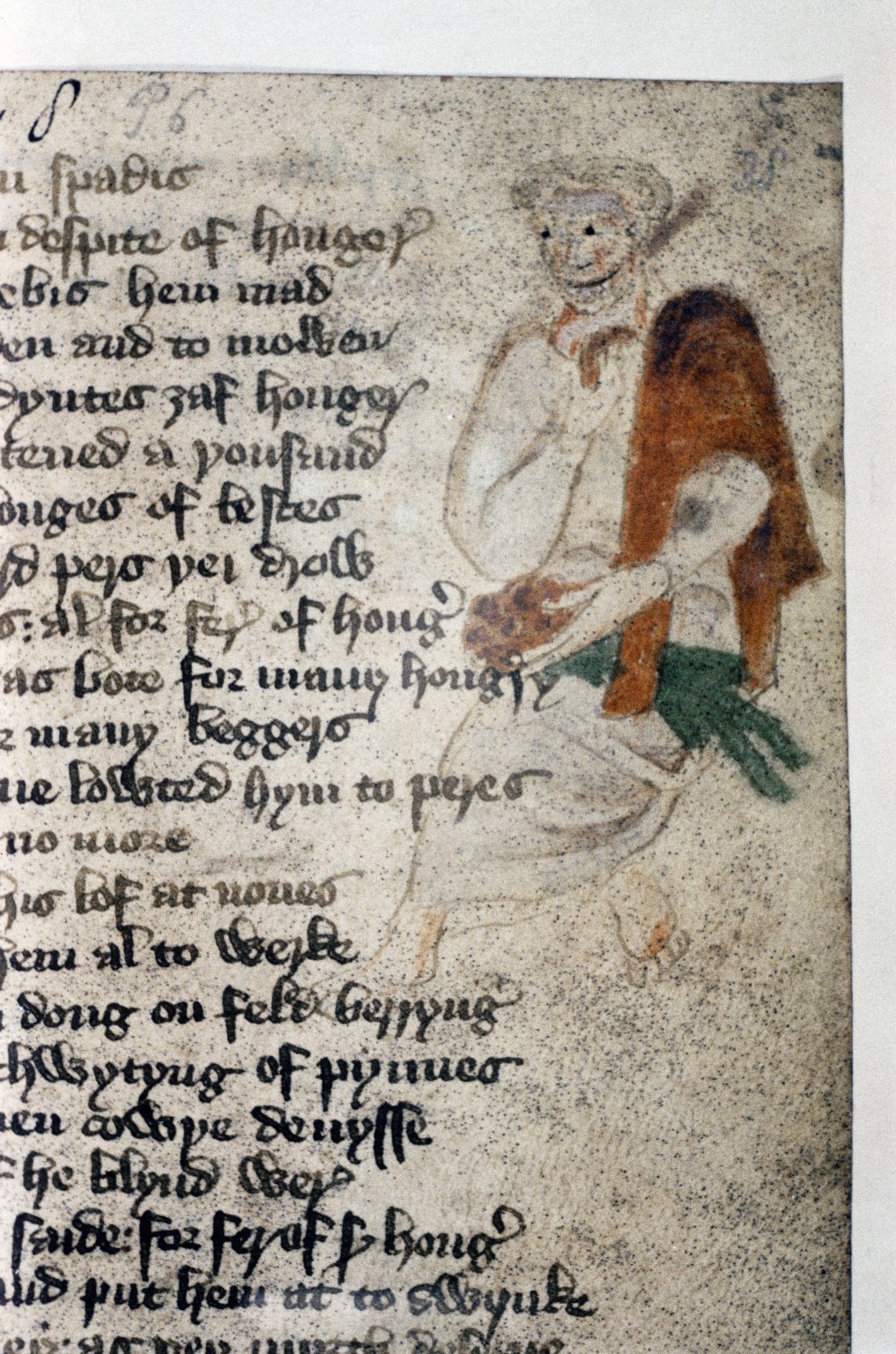

The later part of the day involved the medievalists and cartoonists joining forces. There wasn’t much time to debrief about what each group learned about the other’s world; we were immediately tasked with interpreting pieces from the Newberry’s extensive collection. What awaited us at each table with a colorful photocopy of a folio—anything from a book of hours to Syriac literature!—and various markers, pens, crayons, and more. We worked in groups to bring the piece to life. Some groups imagined backstories as to how the Newberry came to acquire the piece. Others, like my group, tried to expand upon the visual story we saw in the piece itself. We imagined the people depicted in some miniatures as characters in a bigger story, and the cartoonists immediately began storyboarding. As a medievalist, I was out of my element. I’m not used to engaging with my objects of study in such a speculative and imaginative manner. I’m a close reader, so I deal with what’s in front of me. I don’t often dare to think beyond that, to envision what other stories and possibilities characters could encounter. It was incredible to watch the cartoonists sketch out scenes and ideas as we all discussed possible stories and how to depict various actions and events. I honestly enjoyed feeling like a novice and letting those with much more experience in these things take the lead. I was caught up in the unfamiliarity of it all. It was exciting, fun, and collaborative. As the cartoonists finished their scenes, another medievalist and I were entrusted with coloring. We fell into this rhythm of specialized tasks, not too dissimilar from what it would have been like for artists who illuminated manuscripts.

Before we knew it, time was up! We all could’ve used much more time to continue working on our little projects; an hour was clearly not enough. But we had all sufficiently whet our appetites for cartooning and collaboration, so it put us in the right mindset for listening to some of the cartoonists talk about their work and processes. Everyone was incredibly inspiring and advocated for putting our ideas and creativity into the world, even when it can seem like a cold and difficult place. Cartoonists and medievalists and other people who create (and yes, medievalists create with their writing!) don’t work in a vacuum. Our work does not exist to be kept away from others. We all do what we do to share, to enrich, to inform, to educate, to tell stories about what we find important and interesting. We do it for our audiences, whoever those people may be.

***

As I was preparing this blog post, I reached out to Chris and Kristen with several questions. I wanted to get their perspectives on how the event went. Part of it has to do with my gratitude for their efforts: I gained so much joy and inspiration from “Cartooning the Medieval,” and I wanted to share it with the world. It felt important to me to include their voices so that this blog post would be less about my own experiences and more about broader stakes and hopes and dreams. Chris and Kristen were kind enough to reply to my questions via email. I have included my questions and their answers below. Please think of this as an informal interview and a behind-the-scenes bonus that you get read if you’ve gotten this far into the post!:

What were some of the major goals of the workshop and symposium?

KHC: As we truly had no idea what to expect from the symposium, given its highly experimental nature, the biggest goal, I think, was to make sure both discipline groups felt welcome and comfortable and able to enter into conversation with each other. We anticipated a degree of discomfort and anxiety on the part of attendees (and, of course, some excitement and curiosity!) and we took a number of steps intended to dispel these negative sensations, including an extended ice breaker activity (which took over an hour, as opposed to the traditional 5-10 minutes one might expect at these sorts of events) specifically designed to encourage cross-disciplinary mixing right from the outset.

With these conversations started, another important consideration for us was allowing each group to develop a deeper understanding of how the other discipline worked via hands-on exercises. The cartoonists were offered a workshop in book history and how one might work with manuscripts while the medievalists participated in a zine-making workshop. Each workshop gave the participants a basic understanding of approaches and vocabulary used by the other discipline, setting them up to better explore the possibilities of cross-disciplinary collaboration in our later sessions.

CDF: This event was a bit exceptional compared to the programs I’ve done at the Newberry, in that I truly had no idea what was going to happen. From the beginning, my elevator pitch for the conference was always “We want to put medievalists and cartoonists in the same room and just see what happens.” The uncertainty of what would actually come out of that mixture was, unusually for me, kind of a selling point. After all, people seem to always expect the same things out of whatever their professional conferences are, so bringing folks into a space where no one knew what would come out of it added to the excitement dramatically increased the impact.

Like Kristen said, we did have some more concrete ideas in mind of what we expected. Ultimately, we wanted each group to understand how the other side lived, as it were. If medievalists and cartoonists had a better sense of how each group did their work, we thought, that could lay a foundation for these two fields to come together and make things, which would help them develop new, enthusiastic audiences. As Kristen has already proven, cartooning can be a great way to not only effectively share the Middle Ages with communities outside the academy, but also to express aspects of medieval culture that don’t come across well in traditional scholarly publications, so we wanted to make it more possible for medievalists to do that work. At the same time, we also wanted cartoonists to realize that there was an incredible amount of raw material—narratives, visual imagery, mindsets, and so on—that they could use in their art. Just as importantly, we wanted cartoonists to know that there were experts in that raw material who were ready and willing to help them understand it as well.

How do you think medievalists and cartoonists could be more mindful of non-specialist audiences?

KHC: One of the things I find most valuable about discussing my work with non-specialist audiences (whether I am talking about making comics with medievalists or talking about studying Chaucer with cartoonists) is the way these conversations change the way I pay attention to the work I am doing. In a comparison that I have been known to overuse, it’s similar to when a guest visits you in your hometown and suddenly, while showing them around, you are able to appreciate your surroundings anew through the interactions you share as an unofficial tour guide.

I am aware that both of my disciplines (which I love deeply) are often surrounded by misinformation, can be viewed as inscrutable or unwelcoming to the novice, and are sometimes subject to dismissal by those of a more ‘serious’ (traditional) bent. I am also aware, by dint of knowing a large number of professional medievalists and professional cartoonists alike, that those seriously practicing these disciplines tend to be knowledgeable and dedicated to their work, but also endlessly curious and excited to share their expertise. Simply having these conversations with specialists outside of our discipline teaches us how to be mindful in sharing our own work while also showing how enjoyable and valuable these interactions can be.

CDF: When it comes to reaching non-specialists, I feel like cartoonists already do this pretty well, so I don’t feel like I have any advice for them on this score! Medievalists, however, have a much more difficult time. Also, as a bit of a shameless plug, I say a lot more about this in my forthcoming book, so you can check out more of my thoughts when it gets published in September. I think the first step in changing that is to start with the undeniable fact that people outside the academy want to learn about the Middle Ages. The traditional academic system has a way of slowly but surely convincing its members that “no one cares” about the specialist expertise they have, which is why we scholars have so much trouble connecting with anyone who isn’t an academic. So, I would encourage any medievalist working on literally anything to always ask themselves, “How might other people find this interesting/important/fun?” I guarantee you, there are lots of people out there that absolutely do; the trick is convincing yourself that they want to hear from you. And, I suppose, that goes for cartoonists as well; that is, they should also be confident that people want to hear from them about how and why they create their wonderful art, so they shouldn’t hesitate to talk about it!

Storytelling was a motif that popped up throughout the workshop. What do you mean by framing the work that cartoonists and medievalists do as a sort of storytelling?

KHC: I thought of storytelling in the frame of our event as serving a sort of ‘language’ that both of our groups of participants shared. The concept of storytelling, of crafting narrative, serves a critical function for both groups. The best research, when presented in a dry manner, will have difficulty communicating its findings: it makes the reader work so much harder than perhaps they need to. And in comics, the most beautiful art, when lacking the anchor of a solid narrative, will also struggle to connect with an audience. Storytelling highlights an awareness of and sensitivity to the audience that is key for both groups of participants, so it felt like fertile soil in which to plant our conversations.

CDF: For me, the storytelling frame was a way for us to break away from the “scientific” identity of medieval studies that developed in the nineteenth century and is, in my view, doing us a lot of harm. Compared to a word like “research,” storytelling is a much more accessible—and, I suspect, exciting—way to talk about the work that we actually do. I’m a historian by training, and I’ve long felt that what I actually do professionally is tell the stories of real people in the past, stories that are now hidden away in the surviving cultural and material record of the Middle Ages. Because of that, those stories aren’t visible to most people. So, my job as a medievalist is to use the skills I’ve developed (paleography, languages, context, etc.) to make those stories come alive again so people can enjoy and learn from them. At the same time, it’s also my job to teach people how to recover those stories themselves. Thinking about my work that way, I think, allows me to take pride in the academic expertise I have while also preserving the sense of wonder and excitement that the “scientific” medievalists in the 19th century tried (successfully) to drive out of the field. The latter, though, is what gets people outside the academy excited and interested in what we’re doing, and it’s what we need to lean into to going forward.

How do you see the workshop and symposium as bringing fields in dialogue? What are your hopes for the future of collaboration, be it between cartoonists and medievalists or other groups interfacing?

KHC: I have both small-scale hopes and much larger ambitions for this project (we both do)! I’ve been making comics in tandem with and responding to my academic work for years now and the response to this work has been so gratifying. Those teaching this material, in particular, seem to feel drawn to my work as a way to communicate differently with students and to present medieval texts in a surprising way. This makes me so happy! My problem is that making comics is slow and I am just one person. I would love to see more graphic novel adaptations of medieval texts and one of my hopes for this conference is that some of the connections made between participants will result in comics related to medieval studies that I can read and teach in the coming years.

On a grander scale, I am hoping this conference will lead to more experimental events in this vein, encouraging thinking through and working with people and groups beyond our field to enrich the work we are doing with new perspectives. This big-picture question, I think, is best left to Chris and “Sad Ovid.”

CDF: Thank you for the book plug, Kristen! I’ll get to Sad Ovid in a second. I think the most important part of this was giving each group some practical experience doing a (very condensed and simplified) version of the work the other group did. Almost from the beginning, Kristen and I wanted to force medievalists to do some drawing, and cartoonists to do some close looking at medieval sources. That practical knowledge, we thought, would help make dialogue and collaboration much easier, since they would have a better idea of how those collaborations would actually work. I feel like that certainly happened at the conference, and my hope is that these communities will continue to talk, scheme, and actually make things together.

That, as Kristen said, brings us to Sad Ovid. This is an image that I talk about at some length in my forthcoming book, but the short version is this: I think the best illustration of the field of medieval studies right now is an intelligent and successful, yet lonely scholar sitting all alone in a room, wondering why no one pays attention to them. Broadly speaking, this conference was an attempt to help scholars change that identity, both by giving them new ideas about how to share their work and by introducing them to an audience outside the academy that truly wants to know about and use their expertise. I think the same can be done with other audiences as well, and I hope that this conference can be a model for helping other communities find each other, as well.

What are some of your thoughts and reflections about the event? Is there anything you’d like to comment upon, share, etc.?

KHC: Being something of an extrovert, I generally tend to enjoy myself at academic events. I love the excuse to talk to people about their niche passions and ideas. For me, a good conference has vibes a bit reminiscent of attending summer camp as a kid: you spend a packed week making friends and talking about everything under the sun and then you part ways for a year or two. Soon enough, though, you are back to reconnect with old friends and make new ones and it’s like no time has passed. The joy and excitement on the opening days of a good conference feel that same way for me. This event, though, magically felt like that from the very first moment. Despite the fact that 90% of our planning happened over zoom and email, I feel like I have known Chris and our artists my entire life. The excitement and enthusiasm expressed by everyone from artists to attendees, from the wonderful Newberry staff to my incredible co-organizer, was what made this event truly magical. To have been entrusted with a project and with emotions on this scale has been life-changing for me.

For anyone who was not at the event but is eager for a sense of how it felt to be there, I highly encourage a read of cartoonist Marnie Galloway’s post on the event which includes her stunning artist talk. I still get chills every time I read it. https://marniegalloway.substack.com/p/cartooning-the-medieval-artist-talk

CDF: I always knew this program was going to be a fun experience, but I was not prepared for it to be as inspiring and deeply meaningful as it turned out to be. I think both groups came into the event feeling like a niche and unappreciated community within their larger fields (art and academia, respectively), but when we brought them together, they each found out that they were, in fact, “the cool kids,” to use Kristen’s term. I think everyone left with an understanding that people outside their field felt that what they were doing was interesting, important, and really valuable, and that translated into the immense energy and enthusiasm in the room. I think we all felt that exploring this collaboration gave us a lot of hope about the future of our respective fields, especially when we thought of them working together in trying times like these.

Anne Le, Ph.D.

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame