Temperance

Aug 27th, 2010 by irishstories

by Bianca Fernandez

Temperance on the Island: What shape did the Temperance movement take on Beaver Island, especially considering the differing religious norms of Fr. Murray and Fr. Gallagher?

The Temperance Movement in Ireland was one of the greatest social movements the country has experienced, gaining an enrollment of somewhere between three and five million Irish women, men, and children, just five years after Father Mathew began the ‘Cork Total Abstinence Society’ CTAS (Townend 2002:1). Unfortunately, it was not long-lived. The movement broke down after 1843, with an increase in alcohol production, pledge breaking, and the collapse of the local behavior that had supported the movement.

Despite its short-lived nature, in part due to the fact that it was never consolidated, the Temperance movement had a profound effect on Ireland. After Father Mathew became president of the CTAS in April 1838, the organization grew in popularity and membership. By the end of 1842, the Temperance movement was considered a national development. During that period, Father Mathew, ‘the Apostle of Temperance’, was receiving invitations to visit parishes throughout Ireland and even in America (Townend 2002:1).

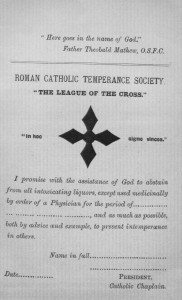

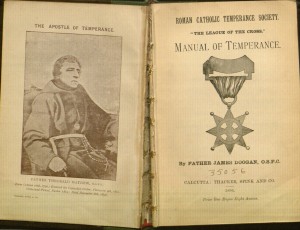

Manual of Temperance, used during the Temperance movement, with image of Father Mathew (Doogan, 1896)

In the Five Points neighborhood in New York City, the Protestants spearheaded the Temperance movement by the 19th century because they viewed the act of drinking as a moral failing and sin (Brighton 2001). This thought was popular in the middle class homes, but it had difficulty permeating into the working and immigrant classes. For the Irish immigrants inFive Points, drinking was a social activity, taking place even at wakes. It was a practice they brought from home and continued in their new American home environment.

Fitts (2001) notes the number of drinking locales that were established, demonstrating the popularity of drinking as a social activity in the area. From the years 1851 to 1854 alone, there were 59 porterhouses, bars and liquor stores in the four blocks that bordered the neighborhood (Fitts 2001:123). The Five Points neighborhood earned a very negative reputation, and many who were outside of the environment attributed the extreme poverty to intemperance, pointing out the ‘evils of alcohol.’

The Temperance movement was driven by a sort of propaganda, creating a deluge of negative images and consequences aimed at turning people away from alcohol. The Manual of Temperance is an excellent example of a text that introduces the life of Father Mathew, which takes on a quality of myth, as well as citing example after example if the sin of drinking (Doogan 1896). For example, it includes a sermon Rev. Father McSweeney of St. Brigid’s Chapel, New York gave to his parishioners. He said

Look at the daily newspapers and read the number of stabbings, murders and other crimes that fill the police courts, and from what cause? All, or very nearly all, are from whiskey drinking. In this parish are families where the men never go to bed sober, and they amuse themselves by abusing their wives and children. They are not all taken home on a shutter, but stagger in and find fault with their unfortunate wives or not having supper. The cursed habit of rum-drinking is bringing destruction on our people. (130-131)

The man and image of Father Mathew reached the United States, holding a prominent place in cities such as New York. Father Mathew and the “Total Abstinence Movement” in Ireland had a profound effect on Ireland and eventually made their way over to the United States, in part due to the high numbers of Irish immigrants during the Famine years (Brighton 2001). Some priests in the United States began starting temperance leagues of their own for their parish. Many of these church based temperance movements were made up of about a thousand men and women, mostly Irish Catholics from the Five Points area. Brighton does a fantastic job of giving historical, social, and moral meaning to the cup with the image of Father Mathew, for it represented righteousness and communicated to people that the family knew the path to salvation: ‘work, diligence, and perseverance’ (Brighton 2001:25).

Although a great deal is known about the Temperance movement in areas that were highly populated by Irish immigrants, such as New York and Boston, not as much is known about Beaver Island. It presents a historical conundrum in many ways. For one, it was an environment well connected in the mid to late 1800s, serving as a refueling port between Chicago and ports along the Michigan coast. Yet, it was also a very isolated and independent community that allowed James Strang to be king of his sect of Mormon followers from 1848 to 1856 as well as creating the perfect environment for the preservation of the Irish language of the subsequent Irish immigrants who made Beaver Island their home. As Connors (1999) expresses, Beaver Island had a unique sense of ‘islandness’, which probably affected the islanders’ religiosity and spirituality.

Beaver Island’s first resident priest was Fr. Patrick Bernard Murray, appointed by Bishop Baraga. He was an Irish man from Ballygovern, Ulster. Although he could not speak Irish, it was hoped that he would be able to relate or at least understand ‘the cantankerous lot of Donegal fishermen” (Connors 1999:167). His role developed into one of a strict schoolteacher, also called ‘a great hammer of heretics,’ who wanted to reform the ‘rascal Irish’, making them a respectable part of the Catholic church community. He was morally opposed to the distilling of whiskey and, not surprisingly, was in support of the temperance movement.

Fr. Murray initiated a temperance crusade in 1863, denying the sacraments to only those who sold whiskey (Connors 1999:174). He also started a temperance society, just as was occurring in other cities, like New York. Entrance into the society required a pledge not to drink, becoming almost like an act of salvation, having to kneel in front of the priest as the person was initiated, but since Fr. Murray only targeted the sellers of this illegal drink, it became like a social reform of sorts (Connors 1999:174).

In 1866, Fr. Gallagher replaced Fr. Murray. He was an Irishman born in County Tyrone and trained for the priesthood in Ottowa, Canada. Fr. Gallagher resided on the island as priest for 32 years, saying mass in Irish, which was still the language spoken amongst the Irish immigrants and the succeeding generations. Under Fr. Gallagher, island religiosity seems to have been different from that of the years when Fr. Murray was the island priest. Less than a third of the congregation attended mass, similar to pre-Famine weekly mass attendance of Árainn Mhór, and there was only one devotional society made up of 20 women who washed and ironed the ceremonial linens. In addition, Fr. Gallagher was not the typical priest, at least according to society’s norms. Fr. Gallagher seems to have had an overall lack of discipline: he got drunk, participated in laical activities, including festive affairs, hunting, gambling, and occasionally fighting. There is even some evidence that he ran a shebeen, or an unlicensed alcohol business, at the Holy Cross rectory (Connors 1999).

Taking all these factors into account, it is interesting to consider what the artifacts may tell us about this period in the Gallagher home site. What shape, if any, did the Temperance movement take on Beaver Island? Was the Gallagher home site a location for the renowned shebeens of the time? Does the analysis of the bottle artifacts reflect the contrasting priests’ positions on temperance?

The Gallagher home site was inhabited by the Warner family from 1856 to 1882, spanning the change from Fr. Murray to Fr. Gallagher. A childless German family, they passed the home on to the Earlys, first generation Irish immigrants who lived and worked on the farm until 1912. Of the fifty-one glass beverage vessels found, 22 of these were liquor or beer bottles — only three of which date to the period of interest.

The bottle shapes of Vessel B 29 found in unit 5, level 3, and Vessel B 32 found in unit 12, level 5 post-date 1892, placing them comfortably within the Early possession of the home site. Vessel B37 from unit 5, level 2, post-dates 1925, which is after Fr. Gallagher’s death but in the midst of when the American Temperance movement was solidified with the Eighteenth Amendment and the National Prohibition Act passed in 1919.

Based solely on the data collected, it does not seem like the Gallagher home site was a possible shebeen unless they used canning jars or other vessels that served multiple purposes. There were no glass bottles that date back to the Warner occupation of the site, which may indicate that they were trying to follow the temperance pledge Murray encouraged his parishioners to follow.

The two bottles, B29 and B32, possibly date back to the Early occupation may indicate the more ‘human’ lifestyle Fr. Gallagher promoted in his religious community. The two bottles do not imply a lack of temperance, but the family may not have pledged to refrain from drinking alcohol completely. In addition, it certainly does not seem as if they were distilling and selling it from their home either. It is possible that the social gathering and drinking was taking place at the rectory or elsewhere on the island. The third bottle was found during what would be the prohibition era of the 1920s, which may say something about compliance or lack thereof with this national legislation.

The glass bottles from the Gallagher homestead — and the absence of liquor bottles during some periods of the sites occupation — raises important questions:

1) What form did the Temperance Movement take on Beaver Island?

2) How was compliance with this ideology and federal prohibition influenced by the local Catholic priest?

3) How did compliance (or not) change over time on the island?

4) Did the remote location of the island shape the degree to which this ideology was adopted?

Literature Cited

Brighton, Stephen A.

2001 Prices that Suit the Times: Shopping for Ceramics at The Five Points. In Becoming New York: The Five Points Neighborhood, Rebecca Yamin, editor, pp. 16-30. The Society for Historical Archaeology, California, Pennsylvania.

Connors, Paul G.

1999 Chapter 4: Island Catholicism. In America’s Emerald Isle: The Cultural Invention of the Irish Fishing Community on Beaver Island, Michigan: Volume 1, pp. 163-222, Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois.

Doogan, Father James, O.S.F.C.

1896 Evils of Intemperance. In Manual of Temperance, pp. 130-131, Thacker, Spink and Co., Calcutta, India.

Fitts, Robert.

2001 The Rhetoric of Reform: The Five Points Missions and the Cult of Domesticity. In Becoming New York: The Five Points Neighborhood, Rebecca Yamin, editor, pp. 115-135. The Society for Historical Archaeology, California, Pennsylvania.

Townend, Paul A.

2002 Introduction: The Temperance Crusade in Ireland, 1838-1848. In Father Mathew, Temperance and Irish Identity, pp. 1-8, Irish Academic Press, Dublin, Ireland.