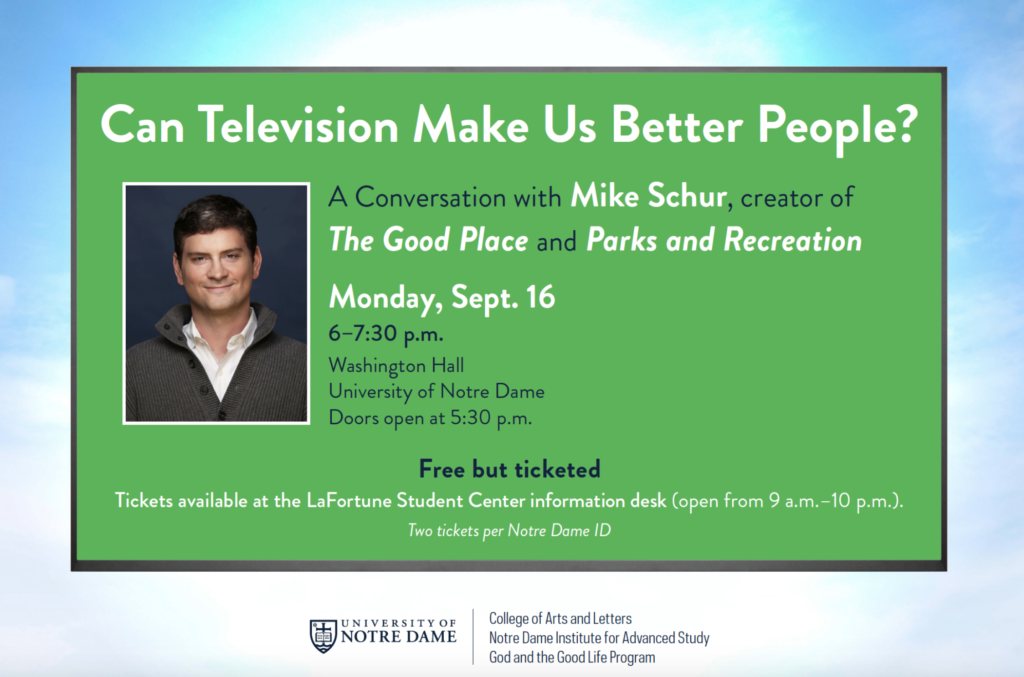

As the Friday before Michael Schur came to campus arrived, the class had an electric buzz. Mike was visiting Notre Dame to speak on a panel composed of our very own fearless leaders Prof. Meghan Sullivan and Christine Becker about the potential of TV to make us better people (more on this to come in our next post).

Although undeniably excited, we still forged on in our foray of The Good Place. For this week’s class we watched Ep 1.13 “Michael’s Gambit” and Ep 2.03 “Dance Dance Resolution,” along with reading the shooting scripts of these episodes, an article by Morreall, “Philosophy of Humor,” and the chapter “Writing the Script” from Alex Epstein’s book Crafty TV Writing. All of these assignments allowed us to establish a basic understanding of typical television episode structures, discuss the differences between final episodes and scripts, and learn about the background and history of humor philosophy.

While the content of The Good Place is obviously quite unique, the structure of this show also provides an interesting point of difference from many other major network comedies. Unlike most other TV seasons that have 22-24 episodes, The Good Place condenses its story into 13 episodes a season.  When Michael Schur pitched the idea for this show to NBC, he had the entire first season planned out, including the length he had in mind and wanting serialized episodes, like the infamous show Lost. As Netflix and other non-network television series are changing the traditional TV model, networks are more open to different forms, which allowed a show like The Good Place to be made.

When Michael Schur pitched the idea for this show to NBC, he had the entire first season planned out, including the length he had in mind and wanting serialized episodes, like the infamous show Lost. As Netflix and other non-network television series are changing the traditional TV model, networks are more open to different forms, which allowed a show like The Good Place to be made.

That being said, the weekly installments of a serialized show serve as a challenge as audiences aren’t able to binge-watch a season in one sitting. Instead, the plot must keep advancing and continue drawing audiences back week after week. For The Good Place, that means Eleanor doesn’t continue trying to hide the fact that she doesn’t belong in the Good Place, instead she confesses in season one episode seven. Similarly, our entire conception of the show is turned upside down in season one episode thirteen with Eleanor’s realization. Once more, the show’s direction completely changes in season two episode three when the characters catching back up to speed on something the audience has been aware of since the end of the first season. Each of these pivotal decisions by the writers of the show represent moments when The Good Place could have had drastically different storylines than it does heading into season four.

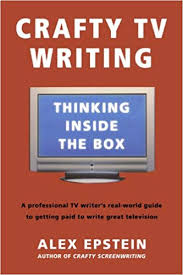

Alex Epstein outlines tradition television structures in his book, Crafty TV Writing, which serves as a helpful comparison to what The Good Place does. In certain regards, The Good Place is a typical television series in terms of structure, but in other regards it differs quite a bit. There is a formula for TV and that formula and conventions are craved, but there must also be an element that makes the show feel different. The Good Place contains similar structures to most TV series, but has a bit extra that makes it feel new, which drives viewers to keep watching through ad breaks

Alex Epstein outlines tradition television structures in his book, Crafty TV Writing, which serves as a helpful comparison to what The Good Place does. In certain regards, The Good Place is a typical television series in terms of structure, but in other regards it differs quite a bit. There is a formula for TV and that formula and conventions are craved, but there must also be an element that makes the show feel different. The Good Place contains similar structures to most TV series, but has a bit extra that makes it feel new, which drives viewers to keep watching through ad breaks

Television episodes are broken down into acts which are storyline sections that are typically separated by ad breaks. These acts are punctuated by act outs or act breaks which are act climaxes that usually lead into an ad break. Depending on the type of show, whether it’s a comedy or drama, or if more ads are desired, there can either be three, four, or six-act structures. With the increasing number of acts, there are progressively more stakes and jeopardy on the line. These act structures typically tend to take this form:

- Teaser (optional): used to hook viewers

- Act One: presents the major narrative complication

- Act Two: pursuit of complication, often ends with new conflict, dilemma, or twist

- Act Three: characters react to new development, usually ends with another new conflict or the stakes are raised

- Act Four: complications are resolved if the show is episodic, or a resolution spawns new enigmas if the show is serial, or we get a bit of both if we’re dealing with an episodic serial series

- Tag (optional): final comment or epilogue

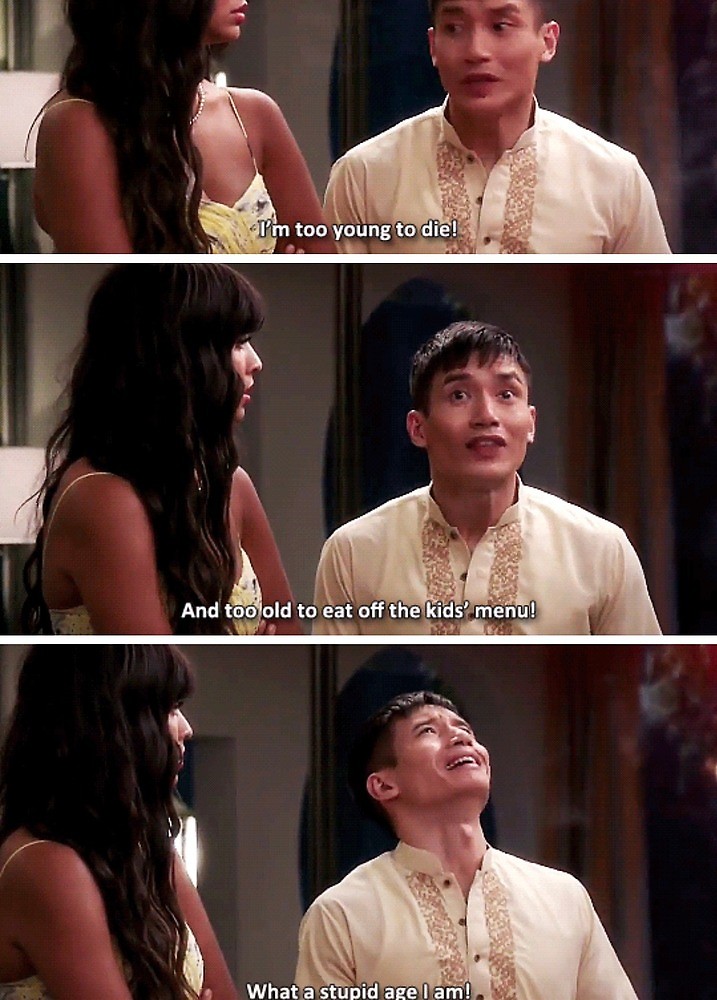

From Eleanor’s Lonely Girl Margarita Mix to the neighborhood’s restaurant puns, The Good Place keeps its audience laughing. We learned various theories that attempt to explain why we find things like Jason’s constant confusion and Janet’s not-a-girl reminders funny. The superiority theory claims that we derive our pleasure because  we’re laughing at people, not with them (I guess we all have a little Tahani in us… ), more of a “punching down” approach with jokes. For example, we find it easy to laugh at Jason’s idiotic behavior because he makes us feel superior and more intelligent. Freud takes a different approach with his relief theory, stating that when we’re relieved of thinking or feeling it comes out as laughter. Lastly, we learned about the incongruity theory, formed by mid-century psychologists; we construct schemas in our mind about things we experience in the world, and when those schemas are altered, we laugh.

we’re laughing at people, not with them (I guess we all have a little Tahani in us… ), more of a “punching down” approach with jokes. For example, we find it easy to laugh at Jason’s idiotic behavior because he makes us feel superior and more intelligent. Freud takes a different approach with his relief theory, stating that when we’re relieved of thinking or feeling it comes out as laughter. Lastly, we learned about the incongruity theory, formed by mid-century psychologists; we construct schemas in our mind about things we experience in the world, and when those schemas are altered, we laugh.

As the semester rolls forward, we’re nearly 98% confident that our class will continue to have its fair share of laughter and learning. We’ve rated this Chapter as follows:

Coolness: 7/11

Dopeness: Extraterrestrial

Humor: (John Mulaney’s The Salt and Pepper Diner Story)2

Dancing Ability: Still Unknown

Smart-brained: Satisfactory