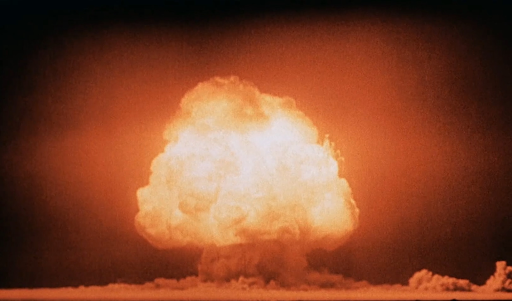

Is declaratory nuclear policy useful? The Soviet Union’s 1982 declaration of a no first use policy was met with inaction by Soviet military leaders who secretly maintained their ex-ante military doctrine. Declaratory policy is nothing without concurrent posture adaptations, suggesting that the United States and China are condemned to nuclear competition for the foreseeable future.

No First Use

China and India currently maintain no first use (NFU) pledges. They agree not to use nuclear weapons against another state unless in retaliation to a nuclear strike, claiming to deter without the option of a pre-emption.1 The United States has pondered an NFU and related declaratory policy changes. The Obama administration stated in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) that the “fundamental role” of US nuclear weapons is to deter attack on the homeland and allies, and President Biden’s 2022 NPR maintained this.2 Both Obama and Biden, however, declined to adopt an NFU policy. The Trump administration maintained in 2018 that an NFU doctrine was not appropriate because it would not reflect the plethora of international threats that the United States faces. Similarly, although Biden, first as Vice President and later as presidential candidate, stated in 2017 and 2020, respectively, that the United States should adopt a “sole purpose” nuclear doctrine, his NPR hesitated to take the next step to its realization.3

The Soviet Union—and, after its dissolution, Russia—held an NFU posture from 1982 to 1993.4 Few analysts consider it when conversing about NFUs today. Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko publicly announced the shift in Soviet doctrine at the United Nations, but it is widely known that the United States did not seriously believe that the Soviets would refrain from launching a pre-emptive nuclear strike in case of desperate emergency.

Understanding what an NFU would look like today depends, at least in part, on what NFUs looked like decades ago. The international climate has become more tense. In theory, an NFU declaration from major nuclear powers would significantly reduce the possibility of escalation because states would not be worried about nuclear threats or use against one another. As mentioned, China utilizes its long-standing NFU in diplomatic conversations today to portray itself as an actor opposed to escalation. Although the adoption of NFUs by countries like the United States and Russia may seem unlikely today,5 a greater understanding of what might bring about a serious pledge and how to maintain it can further the conversation on declaratory nuclear policy.

So, is declaratory policy useful for attenuating security competition? Unfortunately, the Soviet case suggests that political statements can be met with inaction by intransigent military brass. Concurrent changes in nuclear posture would ease this problem, but the United States and China’s nuclear postures are headed in a competitive, instead of conciliatory, direction.

The Soviet NFU

In 1982, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev pledged that the Soviet Union would not launch a pre-emptive nuclear strike. In 1993, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced the termination of the Soviet and Russian NFU.6 Over the course of that decade-plus, the United States intelligence community did not take the Soviet pledge seriously, and believed there was instead a possibility of a Soviet first strike. This is an old fear over NFU policies, however. More interestingly, archival documents indicate that Soviet military leadership did not shift its military doctrine to rule out a first strike possibility.

The Soviet military and its civilian defense leaders resisted the political leadership’s NFU. Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov “believed in first strikes” even though they violated official Soviet policy and led the resistance against a doctrinal shift toward no first use.7 Institutional resistance followed. Documents from East German military archives demonstrate that the Soviet military “retained and exercised” the possibility for a pre-emptive nuclear strike against NATO, even during a contingency in which NATO only used conventional weapons.8 Furthermore, the Soviet NFU policy on its own seems to have turned few heads: US Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger stated during the Reagan administration that recent Soviet SS-20 missile deployments with multiple nuclear warheads each dampened the credibility of the Soviet NFU.9

Contemporaneous CIA analysis of Soviet military doctrine reflected the military reality. A top secret 1983 memorandum stated that Soviet wartime plans for central Europe would include an attempt to pre-empt NATO’s use of nuclear weapons to preclude a large strike on Soviet conventional forces.10 A different 1989 CIA memorandum claimed that the Soviets were “well aware” of their poor economic standing vis-à-vis the West and supposed that the Kremlin may alter its military doctrine towards one which takes a defensive stance.11 The CIA’s implication in this statement that Soviet doctrine was not presently defensive led to the conclusion that the Soviets had not effectively developed a no first use policy.12 Additionally, while the memorandum claimed that Soviet military doctrine focused on the prevention of conventional and nuclear war,13 it analyzed the U.S.-Soviet strategic balance in depth, particularly as former President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative may have impacted stability.14 This may have reflected a distrustful belief about the Soviet NFU, or at least indicated that recent Soviet technological developments placed Moscow on a similar military footing as Washington.

Even a classified briefing of the Defense Policy Panel to the U.S. House Armed Services Committee in 1988 stated that the Soviet NFU declaration represented the political presentation of its military doctrine instead of any military-technical or operational aspects. The concrete measures which the Soviet military took to prepare for and conduct warfighting did not change from before the NFU. The deployment of conventional and nuclear forces retained its “threatening posture.”15

Was the widespread distrust which met the Soviet NFU unique? Perhaps not. Chinese military officials, such as Major General Zhu Chenghu in July 2005, have claimed that Beijing’s NFU has only applied to non-nuclear weapon states.16 While the Chinese government distanced itself from Zhu’s statement, its NFU pledge has historically served propaganda purposes and was conditioned out of necessity and policy instead of peace-loving sentiment. China’s long-standing small nuclear arsenal has made it physically unable to launch a first strike against a nuclear weapon state without expecting complete annihilation, and its nuclear weapons were not created as part of a doctrine which extends past countervalue minimum deterrence.17 Indeed, although Beijing has undertaken significant restraining measures to convince states of its NFU, they are impossible to verify and the United States has continued to distrust China.18

Declaratory Policy and Nuclear Competition

The United States historically has not found NFU pledges to be credible, but analysts overlook an NFU’s civil-military strife. While Soviet political leadership announced an NFU in 1983, military leaders personally stated their opposition and worked to maintain a first strike doctrine.

What does this experience tell the nuclear community about NFUs today? A novel no first use pledge by non-NFU states like Russia and the United States seems unlikely in the midst of today’s tense geopolitical competition, but analysts should also question the domestic viability of such a policy. The U.S. military strongly opposes an NFU and the possible changes in nuclear posture that would follow.19 A U.S. NFU would not necessarily cause a civil-military divide, especially considering civil-military transparency and communication in Washington. But the consequences of other great powers adopting an NFU must be considered. For those states with significant political-military divides, an NFU declaration by political leaders may be met with inaction by military authorities.

This conclusion supports the belief that declaratory policy has little value without a concurrent adaptation of posture by military personnel. Because statements can be empty, the most effective way to create a credible NFU would necessitate action. States could eliminate intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) from their nuclear arsenal (or at least take them off high alert) and instead prioritize the survivable sea-based leg of the triad. This would represent qualified self-deterrence against a first strike because states would be unable to rapidly launch a debilitating first strike and would preclude effective pre-emption. Additionally, given land-based weapons’ vulnerability, their elimination would decrease the benefits and likely success of a first strike. Unfortunately, recent great power policies run counter to these long-term posture commitments that may ease tensions.

The United States is modernizing its ground-based leg with the development of the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD, LGM-35 Sentinel), while China is significantly expanding its siloed ICBM force.20 Neither development benefits relations between Washington and Beijing, and in fact may lead American policymakers to doubt China’s NFU more. Given that China has considered the possibility of placing parts of its forces on a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture, Beijing’s strategic posture is changing, and debates about its NFU remain.21 Even though China has officially reiterated an “unqualified commitment” to its NFU, President Xi Jinping has called for the PLA to establish a “strong system of strategic deterrence,” pointing to a break in nuclear policy that may push American policymakers to question the continuity of the NFU.22 Although Chinese officials claim that LOW would be consistent with the NFU, Washington may link Beijing’s actions on one front of nuclear policy to another and sense a wholesale shift to a more aggressive nuclear doctrine. In a crisis bargaining scenario, uncertainty about an NFU may lead states to assume the worst case scenario.

Regardless of declaratory policy, the United States and China have adopted postures that risk quick escalation. The Chinese NFU declaration, for this reason, does not by itself preclude action-reaction spirals and American doubt about the validity of a no first use posture. The rivalry—for now—may be condemned to competition.

- It remains important to distinguish between China and India’s NFUs, however. While China has gone to great lengths to make its pledge credible, India caveats its NFU by retaining the option to use nuclear weapons in response to a major biological or chemical weapons attack against India or its forces. Additionally, India has eroded belief in its pledge over conventional attack and nuclear preemption as tensions with Pakistan have grown for decades. Cf. Ankit Panda and Vipin Narang, “Sole Purpose is not No First Use: Nuclear Weapons and Declaratory Policy,” War on the Rocks, 22 February 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/02/sole-purpose-is-not-no-first-use-nuclear-weapons-and-declaratory-policy/. ↩︎

- Ernest J. Moniz et al., “U.S. Nuclear Policies for a Safer World,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, June 2021, pp. 7-12; and Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn, “NTI Statement on the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, 28 October 2022, https://www.nti.org/news/nti-statement-on-the-2022-nuclear-posture-review/. ↩︎

- A “sole purpose” declaratory policy states that the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies. Cf. Moniz, “U.S. Nuclear Policies for a Safer World.” ↩︎

- I refer to this primarily as the “Soviet NFU” because of its adoption during the Soviet years and the change in policy soon after the Russian Federation’s birth. ↩︎

- The United States is unlikely to adopt an NFU today because allies, especially those who benefit from extended nuclear deterrence in east Asia, will worry that Washington will not stand up for them. Russia is unlikely to adopt an NFU today, as seen by its consistent use of nuclear threats and forward deployment in Belarus. ↩︎

- Serge Schmemann, “Russia Drops Pledge of No First Use of Atom Arms,” The New York Times, 4 November 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/04/world/russia-drops-pledge-of-no-first-use-of-atom-arms.html. Interestingly, Soviet generals clarified after terminating the NFU that it only applied to non-nuclear weapon states that signed the 1968 NPT, but still not those allied with nuclear weapon states. ↩︎

- Matthew R. Costlow, “A Net Assessment of ‘No First Use’ and ‘Sole Purpose’ Nuclear Policies,” Occasional Paper 1, no. 7 (National Institute Press, 2021), p. 78. ↩︎

- Costlow, “A Net Assessment,” p. 79; and Ankit Panda, “‘No First Use’ and Nuclear Weapons,” Council on Foreign Relations, 17 July 2018, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/no-first-use-and-nuclear-weapons. ↩︎

- Costlow, “A Net Assessment,” p. 82. ↩︎

- “Soviet Planning for Front Nuclear Operations in Central Europe,” Central Intelligence Agency, June 1983, p. 11, archives.gov/files/declassification/iscap/pdf/2012-090-doc1.pdf. ↩︎

- “The Nature of Soviet Military Doctrine,” Central Intelligence Agency, April 1989, pp. 13-14, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000499601.pdf. ↩︎

- NFUs are defensive, instead of offensive, policies, because they are inherently responsive. They can still serve deterrent functions, because they warn against the response a state would face if they were to attack with nuclear weapons. But NFUs are not offensive because they eliminate the possibility of first use and preemption. ↩︎

- “The Nature of Soviet Military Doctrine,” p. 21. ↩︎

- “The Nature of Soviet Military Doctrine,” pp. 18-19. The SDI was intended to intercept ICBMs from space, which many argued would encourage another arms race and undermine established arms-control agreements. Earlier U.S.-Soviet treaties, like the ABM Treaty, were intended to reduce defensive anti-ballistic missile systems that would otherwise have pushed the powers to build more weapons for deterrence and undermined mutual vulnerability. ↩︎

- “General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Military: Assessing His Impact So Far and the Potential for Future Changes,” The Defense Policy Panel of the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 2 August 1988, p. 3, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90M00005R001100030010-1.pdf. ↩︎

- Stephanie Lieggi, “Going Beyond the Stir: The Strategic realities of China’s No-First-Use Policy,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, 31 December 2005, https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/realities-chinas-no-first-use-policy/. ↩︎

- It is unclear how China’s nuclear expansion and modernization will impact this, but its arsenal as of this writing is still unlikely to comprehensively destroy U.S. second-strike capability and maintains an assured retaliation capability. Cf. Henrik Stålhane Hiim, M. Taylor Fravel, and Magnus Langset Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma: China’s Changing Nuclear Posture,” International Security 47, no. 4 (2023): pp. 147-187. ↩︎

- Lieggi, “Going Beyond the Stir”; and Panda and Narang, “Sole Purpose is not No First Use.” Panda and Narang further that China has implemented de-targeting agreements and has unilaterally separated warheads from ICBMS (a process known as de-mating), but because an NFU is a component of declaratory nuclear policy, there is no possible diplomatic arrangement that would verify or enforce a pledge. Furthermore, the pledge alone would not impact capabilities. For Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s distrust of China’s NFU, see Kumar Sundaram and M.V. Ramana, “India and the Policy of No First Use of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1, no. 1 (February 2018): pp. 152-168. ↩︎

- Panda and Narang, “Sole Purpose is not No First Use.” ↩︎

- Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma,” p. 148. Additionally, some scholars have written about the direct impact of new U.S. capabilities, such as ballistic missile defense and CPGS, on China’s ability to launch a retaliatory strike. China expanded its force structure in part to ensure survivability under assured retaliation, but it might be forced to abandon assured retaliation for a first-use posture. Chinese analysts also surmised during the Obama administration that Beijing would retaliate against a U.S. conventional attack on Chinese nuclear weapons with nuclear weapons, violating the NFU. These possibilities point to the unsure nature of declaratory policy. Cf. Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Assuring Assured Retaliation: China’s Nuclear Posture and U.S.-China Strategic Stability,” International Security 40, no. 2 (2015): pp. 8, 21. ↩︎

- Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma,” p. 150. Additionally, some Chinese officials believe that a LOW posture would violate China’s NFU, proving the volatility of declaratory policy. Without concrete actions that distinctly support declaratory policy, the latter is confusing domestically and internationally. Cf. Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma,” pp. 170-171. ↩︎

- Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma,” p. 168. ↩︎