In his essay “The Whiteness of Film Noir,” Eric Lott investigates the way in which film noir “constantly though obliquely invoked the racial dimension” of the figural, moral tension of light against dark (543). Racial exoticism and primitivism, cosmetic masquerade, literal and figural border crossing, verbal and visual coding, and endless examples of characters portrayed as the “other” contribute to works in which race is not blatantly explored or engaged with, yet relied upon to inform moral, ideological, or simply cultural aspects of the world within film noir.

In The Expendable Man by Dorothy B. Hughes, a medical intern named Hugh travels from California to Arizona to attend his niece’s wedding. On the way there, he encounters a pregnant, teenage hitchhiker named Iris who later turns up dead. Hugh’s connection to Iris, however brief, raises questions in the police regarding his possible involvement in her death.

In reading The Expendable Man, it becomes apparent that Hugh’s interaction with Iris, even prior to her death, has inspired feelings of anxiety and paranoia. When first stopping to check on Iris: “A chill sense of apprehension came on him and he wished to hell he hadn’t stopped” (5). As they drive, he is suspicious of her answers to his questions and refuses to stop anywhere but the bus depot, fearful that someone might see them together. Later, at the border crossing from California to Arizona, Hugh has an uncomfortable interaction with overly suspicious border agents. Iris is waiting for him and manipulates Hugh into giving her another ride. “There was absolutely nothing Hugh could do to escape her. To refuse would have been worse than to accede” (20).

Hugh’s anxiety and paranoia surrounding Iris and various law enforcement officials could be read as an older man uncomfortable with the optics of driving alone with a teenage girl. Combined with the visual cues to their respective class standings offered by Hughes (Hugh’s cadillac, Iris’s cheap dye job, etc.) one could be forgiven for interpreting Hugh’s anxiety and paranoia for feelings based on class and gender disparity.

However, though never explicitly stated, Hugh is a Black man. This is defined in contrast to Iris’s clear description as a white girl. Understanding this “constantly though obliquely invoked” racial dimension of the text creates a new layer of understanding in the reader. Instead of simply being a story about a well-off man encountering a poor young girl, we are exposed to the biases, tensions, and dangers that arise when a Black man becomes involved with the sordid, tragic circumstances surrounding a young, murdered, white girl.

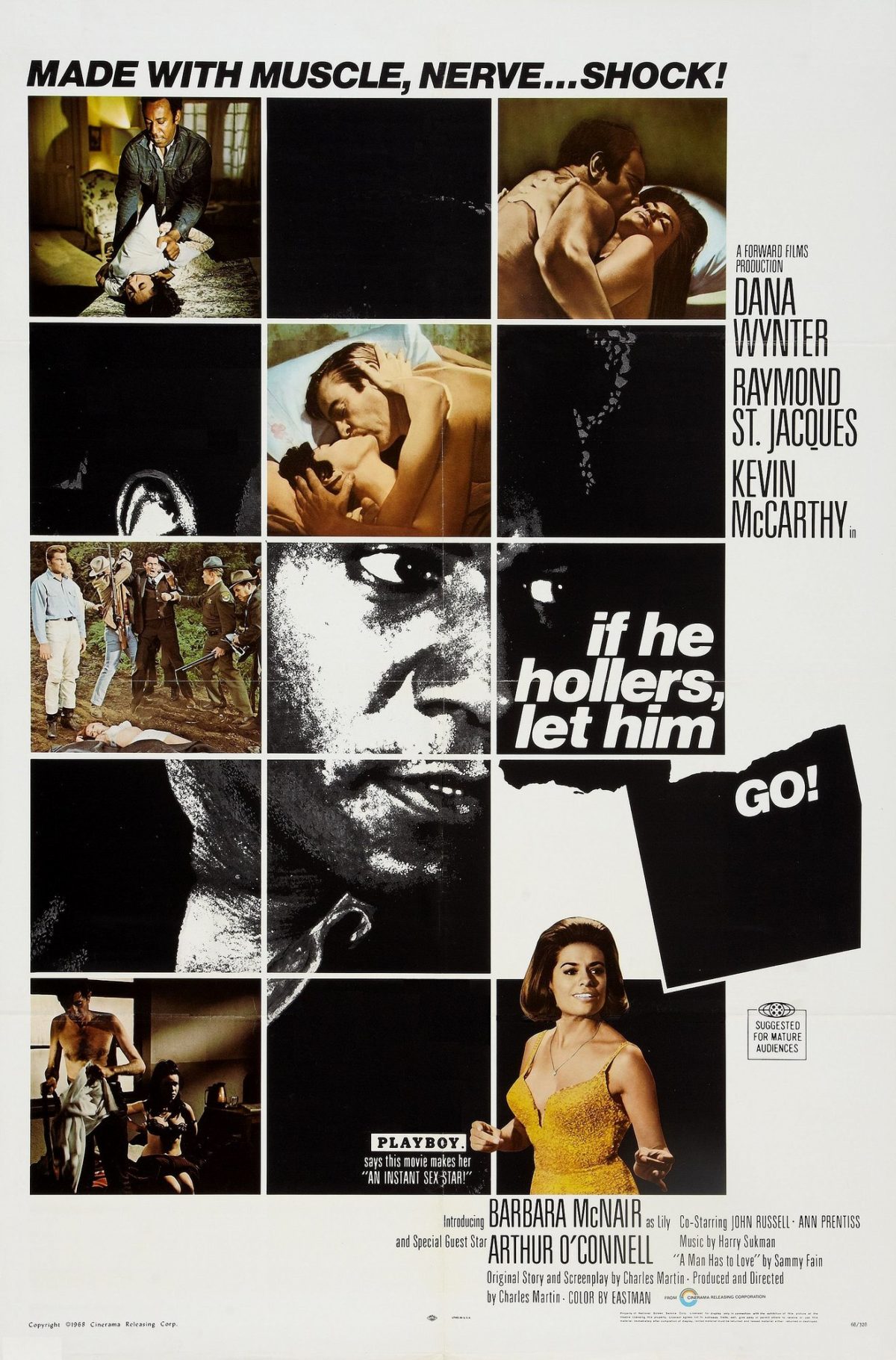

Hughes’s approach to race differs wildly from Chester Himes’s exploration of the matter in If He Hollers Let Him Go. This is likely due to the fact that Hughes is a white woman and Himes is a Black man; their personal experiences inform different approaches to writing race and its effects

I agree with your observation that it would have been easy to read the tension as a welathy older man picking up a younger lower class girl, but the racial dimension increases the tension and paranoia that makes noir so intriguing. As we talked about in class, by not mentioning race initially, Hughes draws in readers of all races before adding on the additional layer of tension. However, I agree that writing as a white woman, she would not be able to articulate the experience as well as a black man writing about a black man.