In my History of Television class, we’re spending a day on 1970s local television using Beyond Our Control as our primary case study, and I’ve assigned the students this post to read about the series. It’s an adaptation of a presentation I delivered last year at the Locating Media Industries conference in London. A primary goal of the conference was to consider how a “focus on locality can help ground our understanding of how media industries are actually inhabited and lived,” so my presentation covered the local conditions that made BOC possible starting in the 1960s and how those conditions changed to bring about its end in 1986. I’ve just tinkered with the text a bit and added a list of suggested clips at the start.

“Locating Beyond Our Control in South Bend”

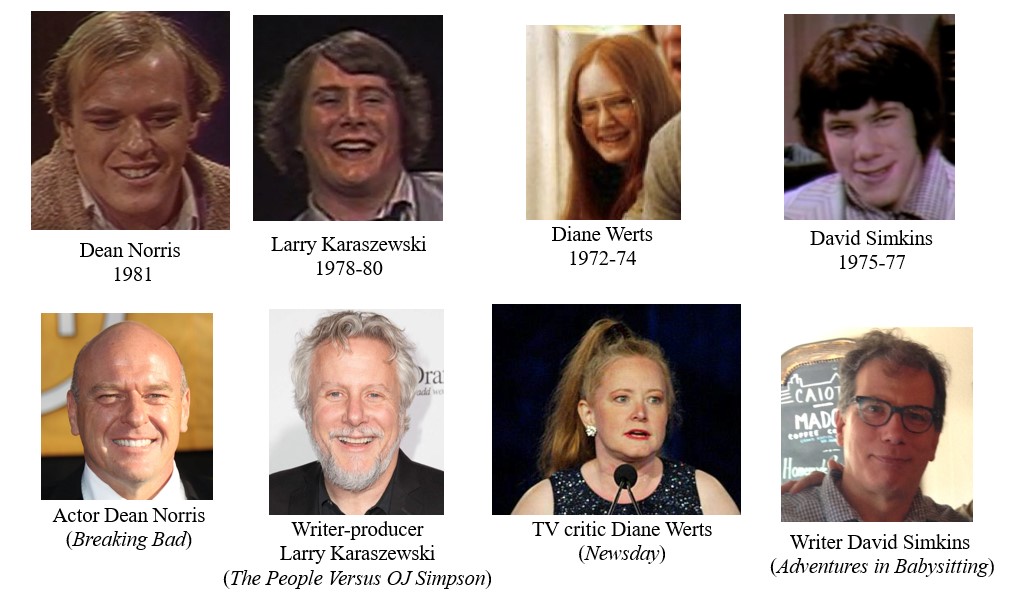

Beyond Our Control is the most important American television comedy almost no one has heard of. It aired 247 half-hour episodes, more than Friends and The Office. It ran for nineteen seasons, longer than all but a few dozen scripted shows in American TV history. And it featured the contributions of such creative luminaries as writer-producer Larry Karaszewski (The People Versus OJ Simpson), actor Dean Norris (Breaking Bad), writer Daniel Waters (Heathers), animator Traci Paige Johnson (Blue’s Clues), TV critic Diane Werts (Newsday), writer Chris Webb (Toy Story 2), novelist Ellen Akins (Home Movie), editor Bob Mowen (The State), and writer-producer David Simkins (Adventures in Babysitting). So why is Beyond Our Control almost unknown in television history? Because it was a sketch comedy series produced at a Midwestern US commercial TV station by high school students, and such material is typically deemed too shallow or trivial for serious academic study or, more sadly, even archival preservation to enable later appreciation and close study of it.

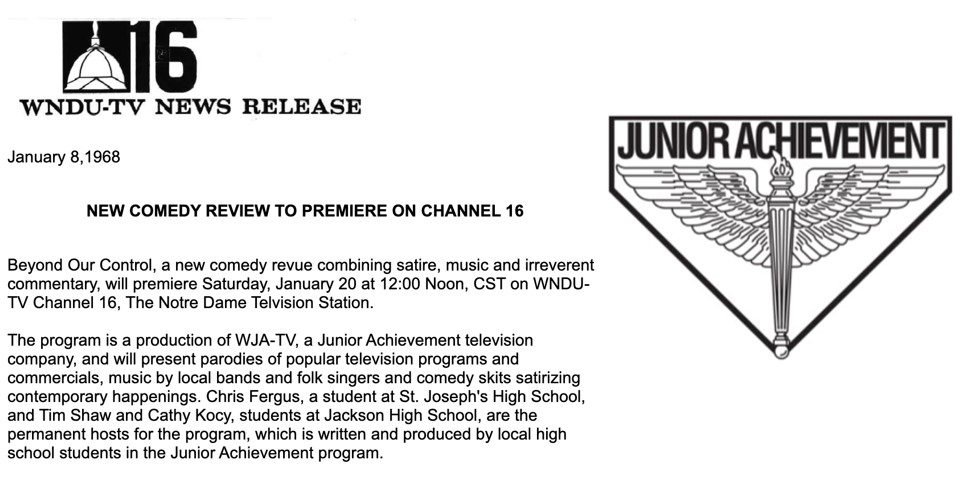

Originating from the city of South Bend in northwestern Indiana and offering thirteen episodes per season in the first quarter of every year from 1968 through 1986, Beyond Our Control was a joint product of Junior Achievement, a nonprofit youth initiative, and WNDU-TV, an NBC affiliate station owned by the University of Notre Dame. Under the guidance of small handful of adult advisers, each year thirty Michiana-area high school students between the ages of 14 and 18 undertook nearly every job required to put a commercial TV series on the air, from writing scripts to operating studio cameras to selling commercial time.

The title for Beyond Our Control stemmed from the routine announcement when a logistical or technical difficulty arose, i.e. “Due to circumstances beyond our control,” something wasn’t going as planned. (See my post about the origins of the title here). It was billed as “a TV show about TV,” featuring chaotic parodies of local and network news and commercials, dramas and sitcoms, game shows and B movies.

To get a general sense of what those sketches were like, check any of these out:

- A game show parody mocking network TV exec Fred Silverman: the NBC Programming Game

- Donna Reed Show parody

- A parody of Disney’s story-songs: The Legend of Bimbo

- If Ingmar Bergman directed a mouthwash commercial

- A parody of a public service announcement

- A parody of the local TV news wars: Channel 1 Action Ladder

- On (Campus) Location with BOC

- Coke ad parody

- Mockery of Roseland (next door to South Bend)

- Stop-motion animation: Emissary

WNDU promotions director and BOC creator Dave Williams described the venture in a 1971 essay for Educational Television: “To encourage talented, creative young people to pursue broadcasting careers, WNDU-TV sought to fashion an educational project which offered maximum opportunity for youthful expression combined with a realistic view of the practical limitations of commercial television.” Because it was commercial television, ad sales were required, so students had to make the actual sales pitches to advertising agencies and sponsors, which ranged from local appliance stores and apartment complexes to national companies like McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. BOC member Phil Frank described, “Talk about doing something in high school that’s really precocious, calling up an ad agency and making appointments, and going in and trying to sell commercials. That was just crazy. I got the McDonald’s account, so I got to drive to Chicago. Actually, I was driven to Chicago, because it was before I had a license. My mom drove me.”

Scores of former Beyond Our Control participants like Frank have shared with me their insights about this formative experience and how it turned them from precocious high school students into influential figures in film, television, publishing, and other pursuits. Through consulting such first-hand accounts and a large collection of extant episodes, sketches, scripts, and production documents — all preserved by Beyond Our Control participants themselves because the experience was so formative and meaningful to them – the book project I’m working on will piece together the distinctive production techniques, formal aesthetics, and complex relational and labor dynamics employed in BOC and explicate the lessons these elements offer for television historians, educators, and local broadcasters today.

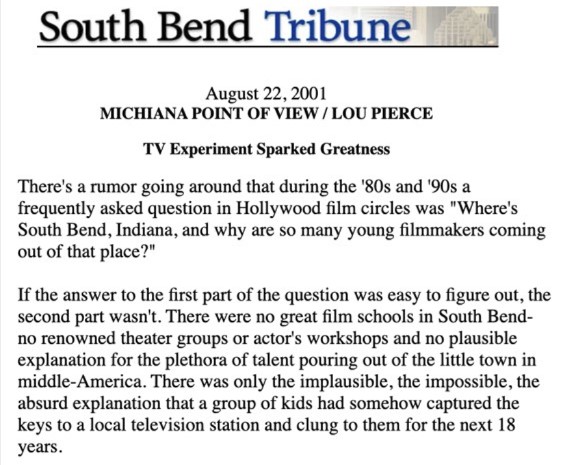

But while the overall question of why Beyond Our Control matters is at the heart of my overall project, for the purposes of this post, I am solely exploring the question of how such a substantial show emerged from what would seem to be a very unlikely place. Former WNDU employee Lou Pierce launched a 2001 South Bend Tribune profile of BOC with a similar question:

A pro-business non-profit organization’s support of a commercial television program on a station owned by Catholic university in which teenagers mocked corporations, advertising, and authority figures seems nearly as implausible as kids holding station keys hostage for nearly two decades. Yet that formula is essentially the answer to Pierce’s question. What made these unprecedented circumstances possible in South Bend?

First, in addition to location, it’s important to also specify time, as BOC arguably could not have existed either before or after the years that it did. The 1960s and 1970s represented a peak period for local television in the US as a dynamic production environment, and WNDU and Junior Achievement found compatible economic and educational aims in giving creative power to Beyond Our Control’s young parodists in the late 1960s. Junior Achievement is a program oriented toward teaching young people the value of entrepreneurship and capitalist business principles, and it had a particularly strong Michiana chapter. Its model in the 1960s involved having regional student groups form companies around a product they made for general sale, usually a small practical good such as a bird feeder, coat rack, or candle. So how did a TV show end up being produced from this model?

Here we have to look to another unique confluence of time and space and a few particular people. WNDU was founded in 1955 by the University of Notre Dame, a private Catholic university, and built on the campus grounds (where Geddes Hall/the Center for Social Concerns is today). It was quite rare for any university to found a commercial station; there were reportedly only four others among about 400 TV stations in operation at the time.

As to why a private religious institution would want to own a commercial station rather than a seemingly altruistic educational, non-profit one, it actually came down to money. The cost of running a station was high, and the regulatory impossibility of using advertising as a revenue source at an educational station would limit its operational and programming ceiling. Notre Dame’s then-Executive Vice President Father Edmund Joyce explained, “It is a major achievement to put on just three hours of really good educational television a week, and that isn’t what I call getting our money’s worth out of the equation.” Related to that aim, the university viewed the broadcast studio as a laboratory in which to train students as future leaders within the mainstream television industry, rather than disappearing into the minimally impactful educational realm. Pious WNDU general manager William Thomas Hamilton explained, “assuming they were good moral men and true – knowledgeable Catholics – they would, as they filled executive positions among stations and networks throughout the country, provide a Christian leavening to an otherwise very secular business.” In 1960, the Executive Director of Junior Achievement of South Bend approached Hamilton about sponsoring a Junior Achievement television program, which a few years later would become Beyond Our Control, and Hamilton viewed this as an ideal opportunity to help fulfill his station’s educational mission.

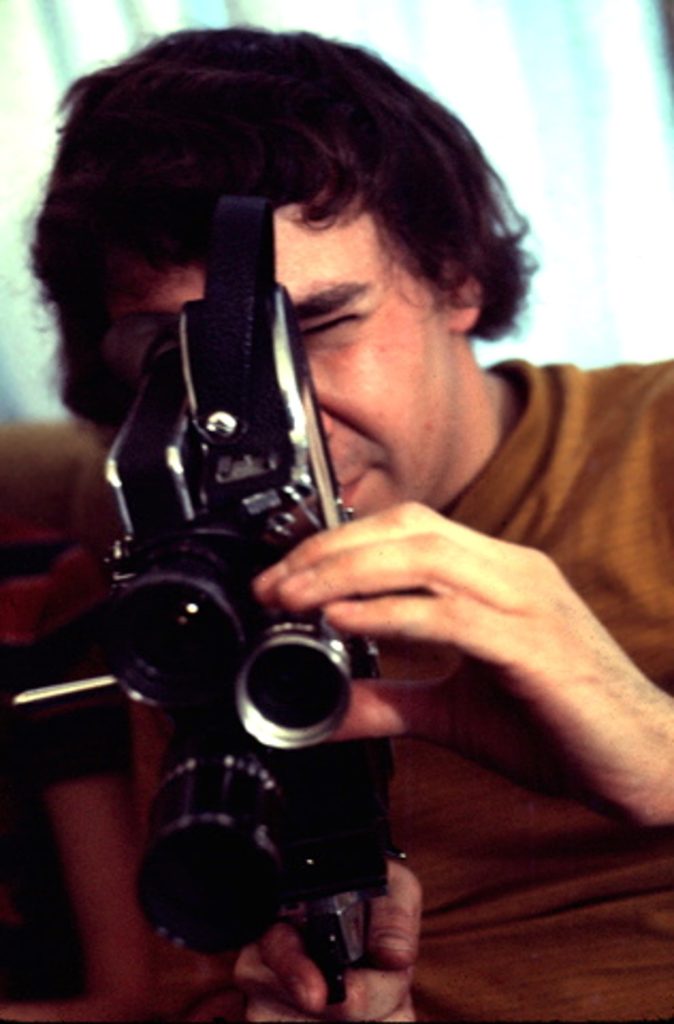

While this put all the pieces in place for the business infrastructure for what would become Beyond Our Control, the creative force behind its emergence was Dave Williams. Williams was a born-and-bred South Bender, and he was highly creative, from a youth spent making Super 8 movies and magazine parodies to conjuring up clever episode summaries for the promotions department he ran at WNDU.

While the initial version of the Junior Achievement series before he came on board was a game show, Williams recognized that the students yearned to produce something more consequential. He explained: teenagers “had grown up with television as babysitter, instructor and constant companion. Somehow, the thought of doing yet another game show was not proving to be a strong attraction to a broadcasting career.” This is another time-specific aspect: BOC’s participants were part of the first generation to grow up with TV but also the youth generation increasingly turning away from TV in this pre-“turn toward relevance” period. At the start of the 1967-68 season, the participants undertook a few weeks of discussion about what kind of series they wanted to make, and, Williams attested, “they decided on a program that would use television as a mirror of American culture” in the vein of That Was the Week That Was, a satirical comedy-variety show featuring topical news spoofs and political sketches. Williams formed a writers’ room with himself in charge as “showrunner,” as we would call it today, but students were responsible for coming up with many of the sketch ideas and jokes.

The teenagers were also trained to undertake every single job tied to producing the series, and they filmed the show in WNDU’s own studio newsroom on Saturday mornings, another crucial factor of location: they were able to use the same studio as the professionals did. This also afforded them the luxury of access to WNDU’s film and licensed music libraries, as well as a ready stash of film stock, which they used to film sketches throughout South Bend using Dave Williams’ Super 8 camera. And of course, all of this massively time-consuming activity happened while everyone was still attending high school and dealing with all the social dynamics that entails, hence the 1973 TV Guide profile headline you see below.

The following two short segments will give you a sense of what they created, and I’ve chosen sketches that directly relate to the South Bend and Notre Dame location. The first is a studio segment mocking the coverage of breaking local news with a premise that the Golden Dome on Notre Dame’s campus had been stolen.

The second clip is a filmed location segment making fun of spurious claims made by automobile ads. (Note: this clip features a local colloquialism. A street pothole was called a chuckhole in Indiana back then, so the voiceover cites “the chuckholed streets of South Bend.”)

In terms of the quality bar, with nearly five hours of original content each season and much of it produced under onerous time pressures, there was plenty of bad lumped in with the good. But while there were passing moments of flubbed lines or mistimed edits, the series does not look at all like an amateur operation. And in fact, Beyond Our Control was good enough to win a major award in direct competition with professional productions, as it was named the lone winner in the television category at the 1977 Chicago International Film Festival based on a one-hour compilation episode.

While I’ve already touched on some of the key infrastructural benefits of the South Bend location – like a strong Junior Achievement chapter, a Notre Dame-owned commercial station with a public service mission and professional-grade studio equipment, and a creative genius and inspiring leader in South Bend-native Dave Williams — we must consider another key factor in the geography of South Bend. Its northern Indiana location meant it drew kids from collar cities with diversity in their populations and a range of economic classes, if not much racial diversity (it was predominantly white, with never more than three out of thirty kids annually being Black).

Also. South Bend then was struggling economically partly due to the abrupt 1963 closure of the largest employer in town, the Studebaker car manufacturer, which presumably meant fewer jobs available for youth and thus more available for BOC. The Michana area also wasn’t so big that kids had a lot of other things to do, nor was it so small that it didn’t have a deep pool of creative, ambitious teenagers. And as far as TV content to draw from for parodies, the proximity to Chicago meant the availability of additional stations like WGN, which was an independent station that aired both well-financed local programming like children’s shows, as well as reruns of network fare and decades worth of old movies.

Unfortunately, the confluence of location and time had a negative effect by the mid-1980s, when nearly all of the unique local pieces that had made BOC possible were dismantled. Dave Williams died in 1977, and though the show would continue for nearly as long as it had lasted with him at the helm, the leadership deficit accrued as each year passed, which made the show increasingly difficult to pull off. Further, the series’ original booster William Thomas Hamilton retired from WNDU in 1980, which removed their public service champion. Not many at WNDU really loved having the kids mucking about in their studio, but as BOC adult advisor Joe Dundon said, “[Hamilton’s] aura often shielded us.” That shield was gone in 1981. Accordingly, when WNDU moved into a brand-new facility in 1982, the station brass barred BOC from using the new studio. The group did persevere for a few more years in a downtown office building, but losing the dedicated studio space was a blow to their production efficiency, as they had to set up the studio infrastructure anew for every episode, and it was a struggle just to produce enough content to make it to air.

After scrambling like that for a few years, they finally received an official cancellation order in 1986 from both Junior Achievement and WNDU. First, the national JA organization shifted away from their singular focus on sponsorship of high school student-run businesses and moved toward in-school presentations for K-12 students. This came home to roost in South Bend in May 1986 when the regional chapter pulled its sponsorship of the BOC group. That didn’t have to result in the end of Beyond Our Control, but Joe Dundon believed it was just the excuse WNDU needed to finally cancel the series, “a financial decision by management,” as he put it. That financial decision proceeded from substantial structural changes in local television wrought by Reagan-era deregulation and consolidation in broadcasting. As individual station owners gave way to high-powered station groups and budgets tightened, the pressure to squeeze every penny out of commercial time slots increased, and the ability of local affiliates to capitalize upon programming freedom and innovation in their non-network hours declined precipitously. In turn, the public service mission of local broadcasting that William Thomas Hamilton had so championed dwindled. Joe Dundon lamented of WNDU’s cancellation order, “I think that BOC was looked upon more as a liability, an irritant, than an asset. If only they could have seen in 1986 the larger vista of what BOC was really producing year-in and year-out in men and women, in creative entertainment, and in present and future goodwill and national publicity for WNDU and South Bend. I know that many can see it now. Too late.” In fact, if someone had come up with the idea for BOC in 1986 rather than in 1967, it’s fair to say it would never have gotten off the ground, illustrating again that media cities are inextricably tied to the circumstances of time and all of its economic and cultural contexts.

Students who had near total control of a TV show for two decades found themselves lacking it in 1986, and it’s quite striking how often “control” comes up as a theme in former members’ reflections in terms of what Beyond Our Control gave them. At an age when you usually have so little control over your life but are mature enough to understand what more control could mean, BOCers truly were beyond the control of the typical authority structures that would normally hold back kids of that age.

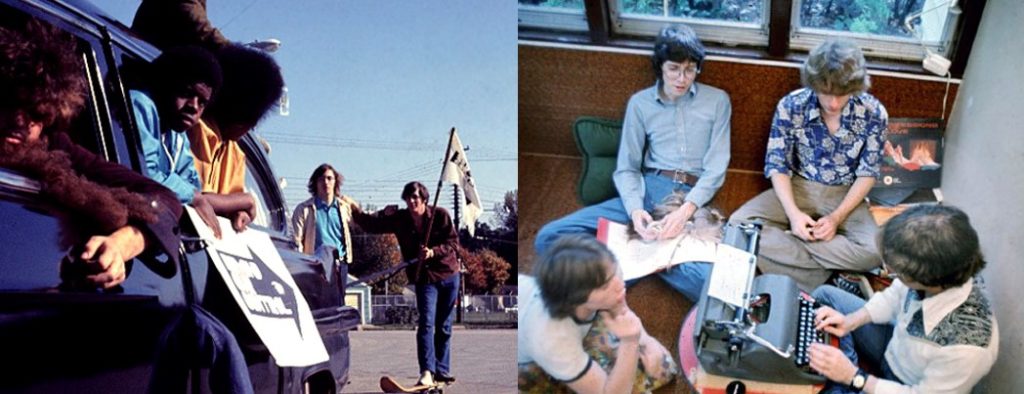

Diane Werts (pictured above left in the writers’ room and on the right selling ad time) said of her early 1970s BOC experience, “…to be creative and express yourself and be recognized for it, by the adults who are mostly looking at you and going, ‘No, you can’t go to that R-rated movie,’ and ‘No, you wrote a weird story,’ and ‘God, that’s not a funny joke.’ I don’t know if I ever would have got outside my own head if it hadn’t been for that. … It was like, I finally found a place where I feel like I belong.” The place that Diane Werts found was almost wholly unique and perhaps unrepeatable, not only in South Bend, but anywhere today.