Conference dates: March 27th – 29th

For the schedule see here.

Registration is free, but required. Register here.

“One can study only what one has first dreamed about,” writes Bachelard in The Psychoanalysis of Fire. Yet, in a text published the very same year, Bachelard seems to cast the relationship between knowledge, images, and dreaming in a more cautious tone: “A science that accepts images is, more than any other, a victim of metaphors. Consequently, the scientific mind must never cease to fight against images, against analogies, and against metaphors.” [Formation of the Scientific Mind]

Between these two quotations we see a formidable dialectic in scientific thought, one that has shaped both the cultural and epistemological contours of science from its earliest emergence to the pressing issues that it faces in the present: On the one hand, science shows the unmistakable fruits of oneiric and imaginative musings; here the scientific mind is the mind that wonders, dreams and trembles, marvelling at the world and getting lost in a labyrinth of phenomena. While on the other, science bears the distinctive mark of a strict, almost austere rationalism; here the scientific mind strives towards the cool, level headed clarity of the day, rigorizing, formalizing, and systematizing the “riotous” freedom of the image, expelling the irrational and subjective to discern the necessity of immutable laws.

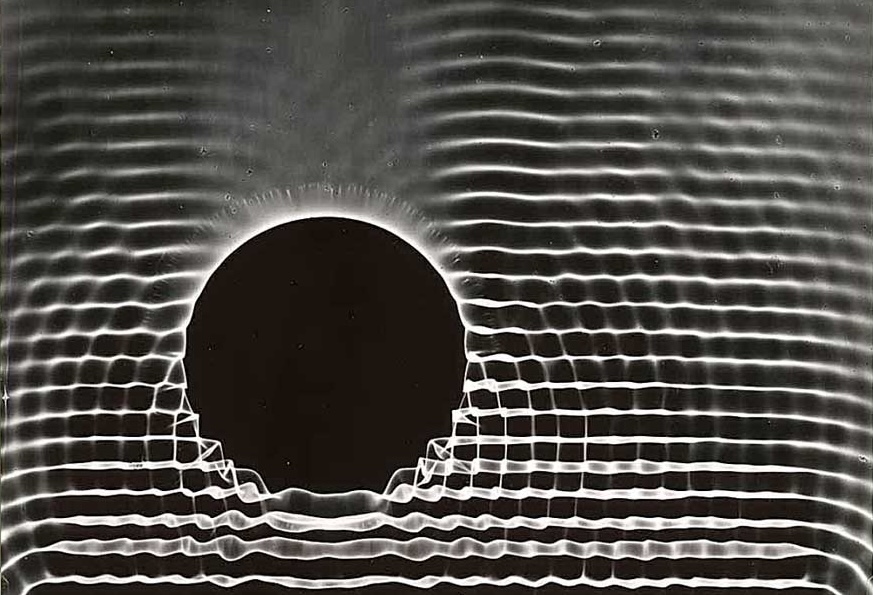

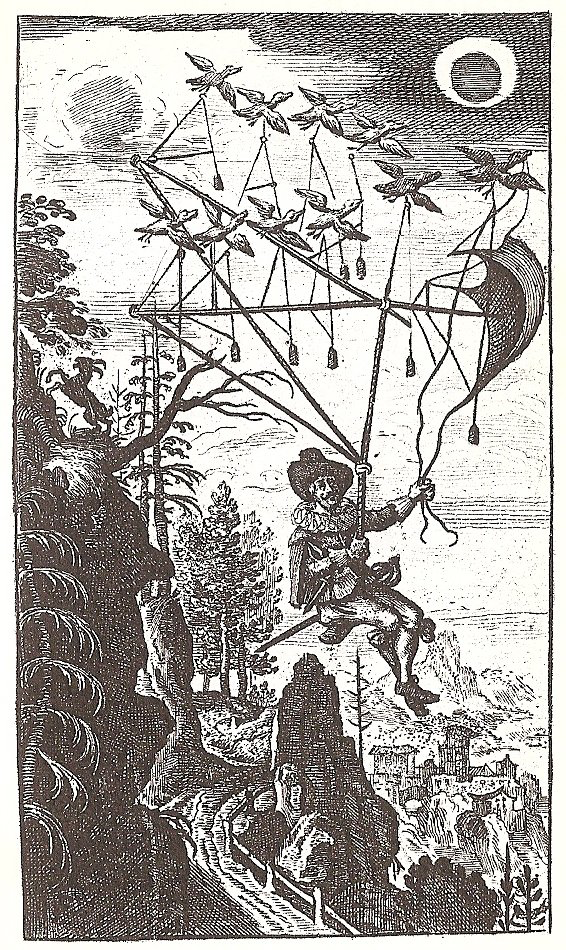

Throughout the history and philosophy of science the imagination makes its appearance, at times encouraging and at others hindering. For example, on 10 November 1619 after spending the day laying out the foundations of a new science, René Descartes had a series of three dreams which left him convinced he had the key to nature’s secrets. On 17 February 1869 Dmitri Mendeleev, exhausted from fruitless investigations, dreamed the ordering of atomic elements that today we know as the periodic table. But in the Spring of 1894 Arthur Worthington praised the efficient workings of his newly acquired photographic camera. He marvelled at its ability to capture the splash patterns of drops of liquid with a mechanical objectivity that, to his surprise, revealed the errors and fantasies into which his imagination and limited senses had led him previously.

The theme of this conference concerns the place of imagination in science, its history, its philosophy, and its contradictions. It asks whether imagination is the truest source of scientific thinking or its greatest obstacle. Do metaphors and images hold the mind back from the clarity of truth, or are they the sole medium for entering into its presence? Should the scientist cultivate and promote free imaginative speculations, or should they discipline their mind by binding it to more rational structures?

This conference invites talks that examine historical cases of imaginative (mythic, poetic, oneiric, and metaphysical) influences on scientific thought, as well as theological and philosophical reflection on the role of imagination in science. Above all, we encourage papers that explore the fraught relationship between science’s dependence on imagination and creativity and its claim to rationalism and objectivity.

Possible questions include:

- What relation does imagination have to the sciences? Is it the truest source of scientific thinking or its greatest obstacle?

- How should we best describe either the current or historical relationship(s) between theological and scientific imagination?

- Do metaphors, images, and dreams hold scientists back from their investigation of the natural world, or are they the sole medium by which scientists can face its complexity, unpredictability, and novelty?

- Should the scientist cultivate and promote free imaginative speculations, or should they discipline their mind by binding it to more rational structures?

- In what ways have scientists, philosophers, and mathematicians made use of imagination in their investigation of the natural world, both in the past and continuing in the present? Has it been something to encourage or something to overcome?

- What kinds of social, environmental, and political contexts give rise to different perspectives on the relation between science and the imagination?

- What are the frontiers of theological imagination given current scientific investigations?

- Do different cultural, metaphysical, and religious perspectives result in salient differences in the kind of relationship that exists between science and the imagination?

- Are there long-term trends in the history of science and the imagination? Has science advanced by progressively removing imagination, dreams, and the oneiric from its practices and methods? Or is the present just as imaginative and dependent on the oneiric as the past?

We would like to thank the John J. Reilly Center for Science, Technology, and Values; the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts; and the Faculty of Science for generous funding and support.

For the schedule see here

Registration is free, but required. Register here.

If you would like to contact us, send us an email: ndhpsconference2025@gmail.com