Alcohol Consumption and Ideology

Aug 4th, 2011 by irishstories

by Adam Lake

Ideological Differences through the Lens of Alcohol Consumption: How did the Strangites’ and the Irish’s vastly differing views on alcohol consumption manifest itself in the archaeological record, and what does this evidence suggest?

A comparative evaluation between the Strangite Mormon and the Irish immigrant cultures highlights many distinct differences. Interestingly, it would be difficult to recognize two cultures whose attitudes towards alcohol consumption differed more. This difference highlights a patent shift in ideologies on Beaver Island in the mid-19th century caused by the influx and outflow of two wholly dissimilar cultures over the course of only a few years.

This reversal in perception of alcohol on the Island is overtly present in the archaeological record found at the Early-Gallagher homestead, suggesting an important shift in Island dynamics as a result of Irish immigration. The transmutation of a profoundly Mormon island into one that reinvented Irish culture can be seen through a shift in the material remnants of these cultures. The archaeological record can be examined to determine whether alcohol played an important role in the lives of the Mormons and the Irish immigrants and whether this influx of alcohol came quickly after the expulsion of the Mormons or was a gradual process.

Strangites and Temperance:

Avoiding alcohol has long been an unequivocal tenet of Mormonism. In a revelation given by Joseph Smith in 1833 known as the “The Word of Wisdom”, Smith states, ”That inasmuch as any man drinketh strong wine or drink among you, behold it is not good” (Smith 1833). As the prophet of the Mormon Church, Smith held divine authority on theology and rules of living; as such, the tradition of abstaining from the “strong drinks” such as tea, coffee, and alcohol are integral to the community’s faith and the Mormon worldview.

Following Smith’s death and the schism of the Mormon Church into two sects, one following James J. Strang and the other Brigham Young, the Mormon community began spreading across America. Facing persecution by Gentiles in Voree, WI, James Strang transported his Mormon followers to the isolated land of Beaver Island, MI. Here he fashioned himself King Strang and took control over many of the aspects of daily life – including temperance.

Beaver Island served as the Strangite Mormon epicenter from 1848-1856, over which time Strang’s power was described by one follower as being, “the only valid government on earth” (Anonymous 1892). Isolation on an island in northern Michigan provided a location where avoiding the temptation of “the strong drink” would likely be easier than in an urban environment. In 1851 Strang claimed to have arduously translated prophetic, brass plates that served as a constitution for a Mormon Kingdom – “The Book of the Law of the Lord”. In it, Strang translates, “Faithful servants of God; godly in their walk and conversation; not given to strong drink” (Strang 1851). In this way, temperance as a lifeway was affirmed on the island.

Though the original Mormon Church had fractured, the principle of abstaining from alcohol was a meaningful characteristic of the new religion as evidenced by its general ubiquity among nearly all Mormon sects. Strang’s temperance policy extended not only to his own flock but also to the entire population of the island. “The temperance laws of the State were strictly enforced with especially good effect among the fishermen and the Indians” (Michigan Pioneer 1892).

A major aspect of the Gentile economy was trading whiskey for fish caught by the Indians. The Gentiles would egregiously swindle the Indians of their fish by trading “Indian Whiskey”, a homebrewed counterfeit of real whiskey comprised of alcohol, red pepper, and tobacco (Weeks 1976). Opposed to Gentile ideologies – alcohol being among them – Strang revealed in the Northern Islander this swindling, effectively destroying the whiskey trade run on Beaver Island in 1851. he hook-like offshoot on of the Eastern end of the isle that defines Paradise Bay – “Whiskey Point” (Figure 1) –still reminds the community of the Gentile’s dealings with the Indian population. A growing feud erupted between the Mormons and the Strangites over ideologies, with Strang saying, “his followers were law-abiding and peaceable people, who were persecuted by a gang of drunken desperados [Gentiles]” (Michigan Pioneer 1892). The depiction of the Gentiles as “drunken desperados” highlights the very negative view Strangite followers had of alcohol and its effect on the community. But while the tensions between the Mormons and Gentiles escalated, many internal struggles arose around policies such as polygamy, resulting in strong dissention among Strang’s followers (Michigan Pioneer 1892). A host of conspirators assassinated him in 1856; his murder resulted in the expulsion of Mormons from the island on July 5, 1856, setting the stage for an immigration surge to the island in the following years of both new immigrants and returning Gentiles who were expelled earlier from the island (Collar 1976).

Irish and Alcohol; Dispelling Stereotypes:

Alcohol, while banned from normal Mormon life, held significant economic power for Gentiles on Beaver Island during the 19th and 20th centuries, leading to harsh conflicts between maintaining Mormon ideology and reaping the monetary benefits of trading alcohol. After the Mormon expulsion there was little stopping the influx of alcohol to the island, merely the cultural proclivity towards its consumption would generate the economic demand for alcoholic products.

Care must be taken in evaluating the drinking habits of the 19th century Beaver Island Irish because many ethnic stereotypes remain today of the drunk, fighting Irish, which can hinder the scope of this piece. To accurately describe the Irish drinking culture it is important to first describe what it is not.

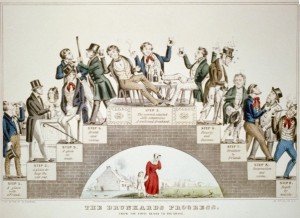

The Irish immigrants came to America during a period of Protestant Revivalism, in which outlandish denunciations of immigrants, Catholics, and “the drinker” permeated society (McGowan 1995). The temperance literature of the time exploited these Protestant worries in a resolute effort to depict non-Protestant individuals as ethnically inferior threats to Americanism (McGowan 1995). Propaganda, such as “The Drunkard’s Progress” (Figure 2), shows how alcohol was portrayed as being a gradual road towards homelessness and eventual suicide. For the Protestant who lost his way there were allegedly potent medicinal cures for alcoholism that “guarantee this to cure anyone of the habit of drinking” for only $5 for 24 doses (Israel 1897). This fight against the saloon was the atmosphere Irish immigrants encountered in the United States.

It is of little surprise then that Irish, being foreign, Catholic drinkers, were under heavy fire from the Reform Movement. Such evidence of these stereotypes is seen in mission pamphlets from the Five Points district of New York. The Five Points was a district renowned as the slum of New York. For anti-Catholic, temperance reformers, Five Points symbolized the epicenter of debauchery and was characterized as a “gang infested hell-hole” where all forms of villainy live. However, archaeological evidence shows that the use of alcohol, crime rates, and even sexual practices were gross caricatures of the reality of Five Points (Fitts 2001). In this light, Irish drinking practices on Beaver Island are not being singled out because they are Irish but because vast differences would be inevitable in comparing any drinking culture to the Mormon religious tradition of temperance.

Alcohol has long been part of the Irish experience and this tradition of drinking found its way across the Atlantic to America. Every type of occasion – funeral, new job, and coming of age – represented an opportunity for alcohol consumption (McGowan 1995). Alcohol also served as social lubrication in the pubs where men would gather and reaffirm their masculinity (McGowan 1995). The importance of alcohol in Irish culture was profoundly important and a vital part of the constructs of community organization and interactions. In 1854, Irish ran three-quarters of New York saloons, though only a third of the population was of Irish descent (McGowan 1995). In the Five Points district the saloons were important meeting spots for the community. Block 160’s corner saloon was the epicenter of political activities where organization would rent out space for their assemblies (Pitts 2001). The saloons serve as not only a location to drink for as a social venue becoming a wide range of characters and ideas.

This importance of the saloon is seen on Beaver Island as well, when in 1859 – only three years after the Mormon expulsion – William “Whiskey” Boyle opened a saloon on the South end of Paradise Bay (Beaver Island Hist. Soc. 1976). In an interview with Beaver Island resident Jim Flanagan, drinking culture was described as, “Everybody would bring a bottle and they would sit around talking, and finally somebody would break out an accordion and start playing or they would put records on.” (Flanagan 2011). Though debate over the actual amount of alcohol consumed is far from settled, scholars generally agree that in the 19th century, alcohol played an important role in defining Irish culture, but not to the extent that many stereotypes fabricated by some Protestant and Temperance groups suggests. With the influx of Irish to Beaver Island it would be unsurprising to see a concurrent increase in alcohol consumption.

Archaeological Evidence:

The archaeological evidence contains one vessel distinctly from the Mormon occupational period from 1840-1856. This one vessel (B6) was found in Unit 11, Level 6, and is likely from a wine bottle. Although this suggests that Strangite adherence to the teachings of Mormon temperance may have been less stringent than originally presumed from historical research, though more data would need to be collected to propose applying such a statement Island-wide. The lack of vessels from this time period suggest that the Mormons were adhering on some level to abstaining from all types of bottled beverages, which possibly could have fallen under the nebulous definition of “strong drink”.

The transition between the Mormons and the Irish occurred in roughly 1856 throughout the island, though at the site in question a German family inhabited the house from 1858-1882 (Rotman et al. 2011). The two vessels found within this time period were both beer bottles. The bottles had embossed marks; one from Grand Rapids and the other from Detroit. The proximity of these two cities to Beaver Island was likely important to the availability of alcohol types to the island.

During the first generation of Irish Immigrants who lived on the site from 1882-1912, 21 of the 33 bottles (63.6%) were identified as alcohol vessels. A few were from Detroit and also Chicago, but the point of origin for the majority could not be identified. For this occupation of the site, there is a significant increase observed in the amount of alcoholic beverages consumed. All but one of the alcohol vessels was identified as beer bottles, that one being a wine bottle. Therefore, beer and ale were likely the most common drinks available on a relatively isolated island, and wine – a drink not common to Irish culture – may have been for special occasions only. Regardless of origin or type of alcohol, it is obvious from the material record that alcohol, which was important in Ireland, persisted in the culture of the island and likely played an important part of community relations.

On a percentage basis, the second generation of Irish (1912-1967) had a higher percentage of vessels containing alcohol [18 out of 25 (72.0%)], even though the Prohibition Era was right in the middle of the period of their occupation at the site. However, three more alcoholic vessels were recovered from the first generation site that from the second generation site, despite the fact that the second generation resided at the site for 25 years longer than the first generation. This suggests that the first generation may have actually consumed more alcohol than the second generation. The Prohibition Era occurred during the period of the second generation, which could be an important limiting factor on the number of vessels found during the period, thus skewing the data and a proper evaluation of alcohol consumption between the first and second generations of Irish.

Contextualization:

It is clear from the material data that alcohol consumption was not completely absent from Beaver Island during the Mormon residency, nor was its “re-introduction” to Beaver Island particularly hindered by either the local Mormon history or isolation. Although, the Gentiles had once traded alcohol on the island with the Native Americans, that dysfunctional system was stopped by the Mormons and it took little time for the Irish – along with the German occupants of this site – to reintroduce alcohol consumption in consonance with the cultures’ traditional values.

Further Questions?

How did the isolation of the island affect the availability of alcohol on the Island?

What ideological and economic factors pushed and pulled on Strang’s Beaver Island population?

Was the apparent decrease in alcohol consumption between the first and second generations real, and if so, what were its causes?

Literature Cited

Beaver Island Historical Society

1976 “Names and Places”. Journal of Beaver Island History 1:165-213.

Collar, Helen

1976 “Irish Migration to Beaver Island”. Journal of Beaver Island History. 1:27-49

Currier, Nathaniel

1846 “The Drunkard’s Progress”. < http://www.safran-arts.com/42day/art/art4mar/curnives/drunkard.html> August 1.

Fitts, Robert

2001 “The Rhetoric of Reform: The Five Points Missions and the Cult of Domesticity,” Historical Archaeology 35(3):115-132.

Flanagan, Jim

2011 Interview by Kasia Ahern and Ariel Terpstra, July 19. Manuscript and audiotape, Beaver Island Oral History Collection 2011. 42:16-43:25.

Israel, Fred (editor)

1993 1897 Sear, Roebuck Catalogue. pp 26. Chelsea House Publishers, New York, New York.

McGowan, Philip

1995 The Intemperate Irish in American Reform Literature. Irish Journal of American Studies. Vol. 4, (Dec., 1995), pp. 49-66

Michigan Pioneer and Historical Records

1892 Sketch of James Jesse Strang and the Mormon Kingdom on Beaver Island. Robert Smith & Co. State Printers and Binders. <www.archive.org>. The Library of Congress. August 2

Pitts, Reginald

2001 “’Suckers, Soap-Locks, Irishmen, and Plug-Uglies’: Block 160, Municipal Politics, and Local Control”. Historical Archaeology. 35(3):89-102.

Rotman, Deborah et al.

2011 Early-Gallagher Homestead 2011 Field Report. Ms. on file with the Department of Anthropoloyg, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana.

Smith, Joseph

1833 The Word of Wisdom; Doctrine and Covenants Section 89. Utah Lighthouse Ministry, < http://www.utlm.org/onlineresources/wordofwisdom.htm>. August 1

Strang, James

1856 The Book of the Law of the Lord. Chapter 32. Royal Press, Saint James, MI.

Weeks, Robert

1976 The Kingdom of Saint James and 19th Century American Utopianism. pp 20-22. The Journal of Beaver Island History: Volume 1.

I’m glad that you enjoyed the article. Thank you for the links as well! Beaver Island holds many interesting disparities between the Irish and Strangites that is present in not only historical documents but the archeology as well.

Very interesting article. Great research. I didn’t know any of this about the Strangites. The unbiased opinion of the Irish was helpful too. Thanks for posting it. An image of the original text for the “Word of Wisdom” revelation given Joseph Smith, as well as a short history of it, can be viewed here: http://josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/revelation-27-february-1833-dc-89

The actual text for the revelation can be read here. Aside from the segment about alcohol, many other applicable health tips are listed in it: http://lds.org/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/89?lang=eng