Domesticity

Aug 27th, 2010 by irishstories

by Jackie Thomas

Domesticity on Beaver Island: A piece of seemingly common whiteware uncovered on the Gallagher Homestead was a section of a Gothic style teapot, which carried significant connotations for the middle classes of the 19th century. Inspired by this sherd, the archeological team invites community members to read on about the importance of this object and contemplate on what conclusions can be drawn about the residents of the Gallagher Homestead.

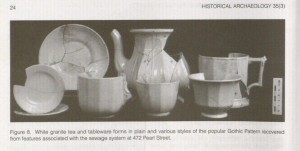

The presence of a striking object at the Gallagher Homestead sparks the possibility of a discussion concerning the depth of Victorian influence in homesteads on Beaver Island. In Unit 11, a sherd of a white gothic style ceramic teapot was uncovered, which is an iconographic representation of the Victorian values treasured by the 19th century middle class. Gothic ceramic patterns feature a paneled look that is ecclesiastically inspired and most often constructed out of white granite. The rise in popularity of the Gothic pattern amongst middle class families was not a random consumer trend but deeply embedded and entrenched within the social history and development of American society, remnants of which are intrinsically tied to modern American culture.

Fitts (1999) notes that the establishment of an American social hierarchy and defined class system was a product of this time, starting with the creation of the middle class. The middle class soon became a unique and distinct entity unto itself, complete with corresponding etiquette and decorum. With a growing negative social stigma attached to proletarians, the separation between the professional and working class grew exponentially.

The middle class was seeking to distance themselves from those of blue-collar status, and “by the 1850s the middle class had developed a distinctive style of living and their own world view” (Fitts 1999:46). This worldview took shape in a number of outlets but none more recognizable than the ‘cult of domesticity’ which was “the ideology surrounding the instruction of children in middle class values” (Fitts 1999:46). During this cultural movement, the home was viewed as a safe haven or a protective shell, which stood in stark contrast to the capitalistic world outside the front door. The function of the home was to shelter and protect the family, most importantly the children, from the brute outside forces.

Fitts (1999) mentions that a rebuttal of the 17th and 18th century Calvinistic beliefs led American Protestants to view the human race and especially children with a softer and more positive lens. With the concept of salvation and a gentle loving God in mind, children were now considered born without sin. This vulnerable and innocent nature of children required that the home be filled with strong familial ties and steadfast values in order to educate children under the sphere of Christian influence. The responsibility to create this antithesis to capitalism fell to the woman or the mother of the house. Women now had “complete control of child rearing and domestic duties” which was certainly aided by the fact that middle class families frequently lived outside cities in more suburban areas, giving them more control over the family. Women set out to “transform their homes into sanctuaries designed to instill their children with Christian values and provide their husbands with refuge from the outside world” (Fitts 1999:47). This is where the incorporation of Gothic styles enters the domestic space.

With inspiration taken from “ecclesiastical elements” the Gothic pattern was created for architecture, ironwork, and furnishings. Gothic shapes within the household rose to popularity because ‘they symbolically associated the home, and specifically the dining room, with the sanctity and community of Gothic churches and contrasted them to the more competitive area of the capitalist marketplace’ (Fitts 1999:47). Along with the Gothic influence, Victorian wives and mothers sought to incorporate more naturalistic forms of beauty into the home, which took shape in ceramics with floral motifs as well as potted plants. The presence of these Gothic elements “could only have enhanced the sacred aspect of women’s domestic role within the ritual of family meals” (Wall 1999:78-79).

The presence of Gothic elements on Beaver Island introduces stimulating and thought-provoking questions for both archeologists and community members to consider. Though we are still learning about the specific history of the Gallagher Homestead, we do know that the Warner family occupied the house from 1858 to 1882 followed by the Earlys from 1882-1912. This piece of Gothic ceramic (found in Unit 11) was most likely owned by the German Warner family.

The Warners were known to have been a childless family, so it is intriguing that Mrs. Warner would have subscribed to the middle class ideals of evangelical motherhood and the cult of domesticity. The fact that the Warners had no children to shield and protect generates questions for contemplation:

1) How did the ideology of the cult of domesticity reach Beaver Island?

2) How did the Warners manage to acquire vessels like Gothic ceramics?

3) Why are these domestic ideals important to a childless family?

4) Did fellow neighbors of Irish decent heavily influence Mr. and Mrs. Warner?

5) What social messages were the Warner’s trying to convey to friends and visitors through their possession of a ceramic with a Gothic pattern?

Literature Cited

Brighton, Stephen A. “Prices That Suit the Times: Shopping for Ceramics at the Five Points.” Historical Archaeology 35.3 (2001): 16-30. Print. 30 July 2010.

Di Zerega Wall, Diana. “Sacred Dinners and Secular Teas: Constructing Domesticity in Mid-19th-Century New York.” Historical Archaeology 25.4 (1991): 69-81. JSTOR. Web. 30 July 2010.

Fitts, Robert K. “The Archaeology of Middle-Class Domesticity and Gentility in Victorian Brooklyn.” Historical Archaeology 33.1 (1999): 39-62. JSTOR. Web. 30 July 2010.

Klein, Terry H. “Nineteenth-Century Ceramics and Models of Consumer Behavior.” Historical Archaeology 25.2 (1991): 77-91. JSTOR. Web. 30 July 2010.