Saints’ Medals and the Sídhe

Aug 4th, 2011 by irishstories

by Caroline Maloney

Navigating Celtic Spirituality on Beaver Island: What is the archaeological evidence for religious and spiritual life on the island?

When a Jubilee Medal commemorating the 1400th anniversary of the birth of St. Benedict was recovered during the excavation at the Gallagher Homestead, the medal presented an unusual glimpse into the intricate spirituality of Irish-American islanders. Bearing on one side an image of St. Benedict standing before the shattered poison cup of Satan and holding the Cross of Christ, and on the other side a cross-adorned protecting shield to deflect evil, this medal was believed by Catholics to help ward off witchcraft, curses, and other diabolical dangers (Figure 1). The St. Benedict Jubilee medal was traditionally worn on rosaries, carried by those seeking to avoid tempests on land or sea, and even buried in fields or placed in house foundations for protection (Our Lady of the Rosary Library [OLRL] 2011).

The medal was first struck in Monte Cassino, Italy, in 1880 (OLRL 2011) and it probably did not become entirely ubiquitous until several years later. Although a precise date for the medal could not be determined, the artifact’s provenience seems to suggest that it specifically belonged to the first-generation Irish-American residents of the homestead. As such, the St. Benedict Jubilee medal is remarkable in that it invites us to muse over the spiritual experience of first-generation Irish-American immigrants to Beaver Island in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The medal represents their remarkably complex and rich spiritual reality manifest in the compatibility between a symbol used to ward off the pagan supernatural and their simultaneous maintenance of traditional Irish fairy lore. This essay will use the St. Benedict Jubilee medal as an entry-point into an exploration of the nature of early Irish-American spirituality at Beaver Island and how this vibrant worldview was maintained across the first generation through island life itself.

The Catholic church of Árainn Mhór, dedicated to the seventh-century Irish Saint Crone, was built just four years before the Catholic Emancipation of 1829 (Teach Phobail Naomh Chróine [TPNC] 2011). Before the construction of the church, Mass was celebrated secretly at Mass rocks across the island and the faith had all the informality, flexibility, and subjectivity of pre-Famine Irish Catholicism (TPNC 2011). Whereas the mid-nineteenth-century Great Famine brought a catastrophic end to many of Irish Catholicism’s powerful monastic and folk traditions, Catholicism on Árainn Mhór may have escaped this destruction due to its relative isolation, poverty, and alienation from the forces of Anglicization (Connors 1999:184-185).

Because “a people’s collective spirit is shaped primarily by two factors: their shared history together, and the landscapes wherein they dwell,” the history and island landscape of Árainn Mhór can be clearly seen to have shaped the collective spiritual ethos that emerged on Beaver Island (Mullin-Norgaard 2002:201). When immigrants from Árainn Mhór arrived at Beaver Island in the 1880s, the rurality and isolation of their new home precluded the large-scale cultural and religious assimilation experienced by their urban counterparts (Connaghan 2011; Connors 1999:187-188). Experiencing instead a similar isolationism and stability of identity that their ancestors had known onÁrainn Mhór, Irish immigrants on Beaver Island initially engaged in a spirituality remarkably close to that which had existed on Árainn Mhór (Connors 1999:187-188). Even though dialogue between Irish-Americans on Beaver Island and the new American culture surrounding them made their religion a hybrid construct in some sense, the continuity that existed between Árainn Mhór and Beaver Island is revealed in the following shared characteristics: “Gaelic [language] sermons, belief in non-Christian supernatural beings, irregular church attendance, inadequate financial support, and the absence of devotional sodalities and confraternities” (Connors 1999:166). Administrative ecclesiological records from the two islands reveal that early Irish Catholics of Beaver Island practiced their faith as they had on Árainn Mhór: often informally in private spaces, within their native language, and only on the periphery of Roman administration (Connors 1999:166).

Given the dark magic-deflecting properties of the St. Benedict Jubilee medal from the Gallagher Homestead, it is imperative to our understanding of early Celtic spirituality on Beaver Island to explore more in depth the islanders’ belief in fairies. The colorful Irish tradition of fairy lore, though threatened by the decimation of the Great Famine, did indeed survive and travel across the ocean with Irish immigrants to America (Connors 1999:181). Irish fairy lore rapidly fell away, however, upon reaching the urban industrial environment of immigrant quarters in American cities (Collar 1996A). On the pastoral shores of Beaver Island, contrastingly, Irish immigrants maintained their belief in fairy lore for at least one generation. Once again, island life itself seems to have preserved this aspect of Irish spirituality at Beaver Island; partial cultural isolation, Irish language usage, and a lifestyle more bound to nature than that of their urban-dwelling Irish-American countrymen may have been the reasons why folklore lasted longer on Beaver Island.

Fortunately, several tales of the spiritual and supernatural from first-generation Irish-Americans of Beaver Island have been recorded. As in many folktales from Ireland, the Beaver Island folktales are essentially bound to the local landscape. For example, Ellen Malloy observed a group of fairies standing on the Big Stone at Boyle’s Beach and another group of elderly island women observed fairies dancing on the “Fairy Hill” behind the house of Salty Gallagher (Collar 1996B; Collar 1996C).

Another illustration of Beaver Island folklore can be seen in the mythical dimensions of Bonner’s Bluff Spring, which has been described in the following way:

An Island woman first told me about this beautiful spring. It was a place, she said, where people from all over the Island had come to sojourn and sip from the clear waters for over 100 years. She added that there had been a tin cup there for visitors for many years. It was a tradition that sounded to me strongly reminiscent of the pilgrimages to sacred springs and wells that people make in Ireland to this day (Mullin-Norgaard 2002:217).

The similarities between Bonner’s Bluff Spring and the Irish tradition of holy wells do indeed seem striking. Scattered throughout the Irish landscape (Figure 2) and numbering over 3,000, Irish holy wells first found their origins in pre-Christian, naturalistic ritual but through syncretism became an important part of pre-Famine Catholic practice (Downey and O’Sullivan 2006:37). Although these types of folktales have generally been lost through time, those that have survived speak confidently to the continuity of more pagan or pre-Famine Catholic aspects of Irish spirituality between Árainn Mhór and Beaver Island.

Ultimately, it seems that those from Árainn Mhór who immigrated in the 1880s to Beaver Island engaged in a form of Celtic spirituality that was more representative of local island culture rather than contemporary Irish culture at large. The religious atmosphere from which people of Árainn Mhór had come, though perhaps ‘truly Irish’ in the pre-Famine sense, would have been unique to the isolated islands off the coast of Ireland by the late nineteenth century (Hill 2011; Connors 183-185). Immigrants to Beaver Island carried this religious attitude with them to the new world, and they were able to maintain it in a truly unique way due to their rural island settlement. The unusualness of late nineteenth-century Beaver Island Catholicism stems from the fact that “by the 1880s, the vast majority of Irish American Catholics had undergone a profound religious alteration which stressed pietism, rectitude, and authoritarianism” (Connors 1999:182-183).

This sweeping religious change did eventually come to Beaver Island, gaining strength under the direction of Father Alexander Zugelder following the turn of the twentieth century (Connaghan 2011; Connors 1999:166,219-220). With the loss of Irish language and cultural isolation on Beaver Island in the twentieth century, the pre-Famine characteristics of Irish Catholicism disappeared. Increased devotionalism, new religious orders, greater mass attendance, and a swift disappearance of pagan folktales are tell-tale signs that Beaver Island Catholicism at last gave way to the more homogenized, institutionalized, and pious Catholicism that was popular across mainland America (Connaghan 2011). Another religious medal found at the Gallagher Homestead, this one gold in color and bearing an image of Jesus in commemoration of the Holy Year of 1950, dates from the second-generational, devotional period of Catholicism on Beaver Island (Figure 3).

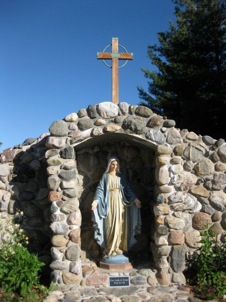

Fascinatingly, the Celtic spirituality of first-generation Irish-Americans is as important today as ever while Irish-descended Beaver Islanders reevaluate the origins and special ethnic meaning of their religion. In the late twentieth century, the devotional and ethnically-sterile form of Catholicism on Beaver Island seems to have witnessed a rekindling of interest in the specifically Celtic strand of Catholicism of the ancestors. A number of archaeological features of the Beaver Island landscape point to this Celtic spiritual revival. In the Holy Cross Church in St. James, for example, there is now a painting of the great Irish saint Colmcille, a statue of St. Patrick holding a shamrock, and a picture of one of the stained glass windows from St. Crone’s Church on Árainn Mhór. Another Celtic-spiritual feature of the present Beaver Island landscape is the recently-built Arranmore Grotto (Figure 4), which coheres a statue of the Blessed Virgin, a Celtic cross, and a piece of glass from the lighthouse of Árainn Mhór. The island’s past and present seem to concur that although “the ‘Celtic Spirit’ first arrived on Beaver Island with those Irish settlers a century and a half ago… it is important to remember that the spirit of a people is a strong quality that is always seeking to recreate itself” (Mullin-Norgaard 2002:203).

This study of Celtic spirituality on Beaver Island, MI, raises some interesting questions for contemplation:

1) What role did Fr. Peter Gallagher play in maintaining the continuity between types of Catholicism on Árainn Mhór and on Beaver Island?

2) What did the process of devotional revolution look like on Beaver Island? What types of devotional practices did Irish-descended Beaver Island families engage in?

Literature Cited

Collar, Helen

1996A Ireland-Mythology. Beaver Island – Helen Collar Papers, Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University. <http://clarke.cmich.edu/resource_tab/information_and_exhibits/beaver_island_history/subject_cards/ireland_cards/mythology.html> 29 July 2011.

Collar, Helen

1996B Biographical Papers Letter M, Page 1. Beaver Island – Helen Collar Papers, Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University. <http://clarke.cmich.edu/resource_tab/information_and_exhibits/beaver_island_history/biographical_cards/biographical_m.html> 29 July 2011.

Collar, Helen

1996C Subject Card – Beaver Island and Michigan: Fairies. Beaver Island – Helen Collar Papers, Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University. <http://clarke.cmich.edu/resource_tab/information_and_exhibits/beaver_island_history/subject_cards/beaver_island_cards/fairies.html> 29 July 2011.

Connaghan, Dan

2011 Interview by Kasia Ahern and Caroline Maloney, 7 July. Manuscript and audio tape. Beaver Island Historical Society Oral History Project, Beaver Island, MI.

Connors, Paul

1999 America’s Emerald Isle: The Cultural Invention of the Irish Fishing Community on Beaver Island, Michigan. Doctoral dissertation, Loyola University Chicago, Ann Arbor, MI. Proquest, <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.library.nd.edu/pqdweb?did=733470731&sid=1&Fmt=2&clientId=11150&RQT=309&VName=PQD> 29 July 2011: 166, 180-188, 219-220.

Downey, Liam and Muiris O’Sullivan

2006 Holy Wells. Archaeology Ireland 20 (1): 37.

Hill, Myrtle

2011 Ireland: Culture & Religion, 1815-1870. Multitext Project in Irish History: Emancipation, Famine & Religion: Ireland Under the Union, 1815-1870, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland. <http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Ireland_culture_amp_religion_1815ndash1870#1ReligioninprefamineIreland> 2 August 2011.

2011 History of Saint Crone’s. Teach Phobail Naomh Chróine, Arranmore, Ireland. http://www.arainnmhor.com/stcrones/Teach_Phobail_Naomh_Chroine/History.html> 27 July 2011.

2011 The Jubilee Medal of St. Benedict. Our Lady of the Rosary Library, Prospect, KY. <http://olrl.org/sacramental/benedictmedal.shtml> 28 July 2011.

Mullin-Norgaard, Jim

2002 Beaver Island and the Celtic Spirit. The Journal of Beaver Island History 5: 201, 203, 217.

My grandfather (who helped raise us) had Patrick Malloy and Mary Mooney of Arranmore, and Beaver Island for his grandparents. Their daughter Susan Malloy married William Levi Brown (not his real last name but that is noted somewhere in island history notes). He believed in fairies and I remember him tell us about them when we were small. He said even rocks can be a home for a fairy so be respectful of all things natural. He used to put out whisky in a thimble.