Looking back at the Monster

by Piper Whitecotton

Storm begins with a typical horror movie intro. A couple is alone and isolated. The setting is gloomy and monotone with dull colors. The intro music is foreboding and hints that something unpleasant is to come. The plot begins when the couple hears an unknown sound and investigates. The strings’ vibrato creates suspense as the couple rushes downstairs. The music cuts out and the thunderstorm fills the background as the couple argues. Then a distinguishable thud incites the suspenseful music to resume and the couple to further investigate. The woman reaches towards the table and her hand hovers over a pair of scissors before grabbing onto a flashlight. Once again, the music cuts out when the man opens the door and the rain is the only ambient sound. When the music stops in situations like this, it creates anticipation for the audience with its eerie stillness. The viewer expects for something to jump out of that stillness, but the question is what will emerge and when. The music is generic as “composers of horror films typically avoid memorable melodies in favor of musical textures”. Researchers Meinel and Bullerjahn have also shown that audiences experience elevated stress, heart rates, and interest, when horror films contain music that is synchronized to the film’s images.

The thunder and music become one as the couple starts to panic as their house is bombarded with mysterious banging noises. The intruder circles the couple as if eyeing its prey and delighting in their fear. The woman glances over while the music crescendos. Her eyes are full of fear and confusion: she doesn’t understand the intruder. Here the audience starts to question the nature of the threat and its identity. The couple does not exude the petrified fear that if a killer was chasing them, even having the nerve to try and talk to them and tell them off for following them. Every time the intruder relocated with a hard cut the couple identifies them.

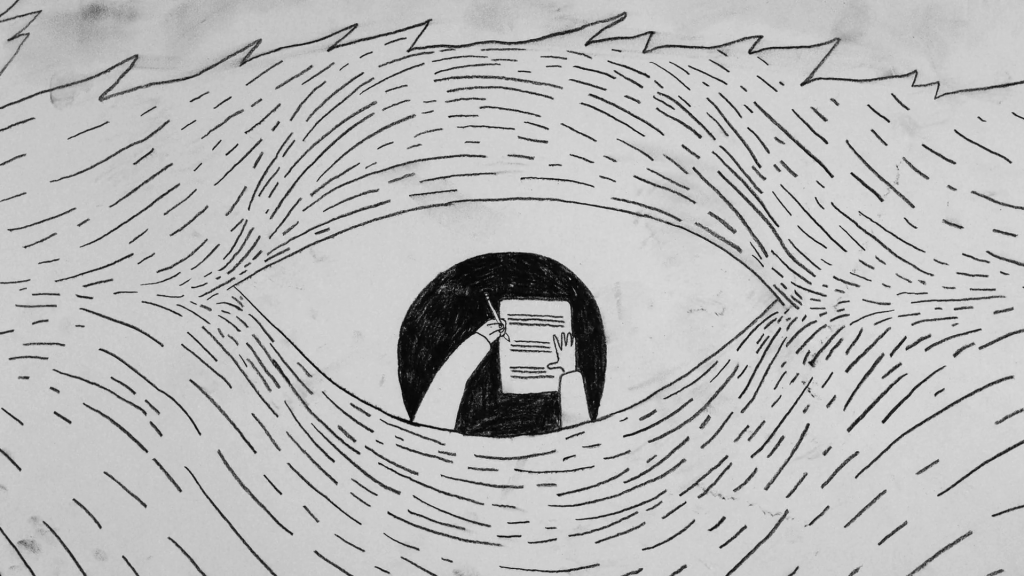

The director then makes an interesting creative choice: the terrified couple in hiding shifts the mindset of the viewers. The woman says, “they are watching us” and the man replies, “like in a movie.” This completely flips the audience’s perspective. As an audience member, I had just assumed that the camera was acting as the eyes of the intruder, but with these words, the identity of the intruder became more complex. The woman knew we were watching her and breaks the fourth wall. The intruder, now known as the camera, follows them throughout their house as an all-seeing eye. The camera displays a quirky personality that loves to tease the couple almost in jest, adding to the comedic aspect of the film. While the couple tries to end the film by doing nothing to further the plot, the camera goes along with the idea by fading out the screen as if to end the film, only to return in full force with the music. The music seems to not have had the same revelation as the woman and is anempathic to the situation. The camera takes pleasure in the couple’s fear and displays voyeurism at its finest, stalking the couple and observing the couple’s stimulating story without their consent. They are like a predator, hungry for a story, and the couple is their prey.

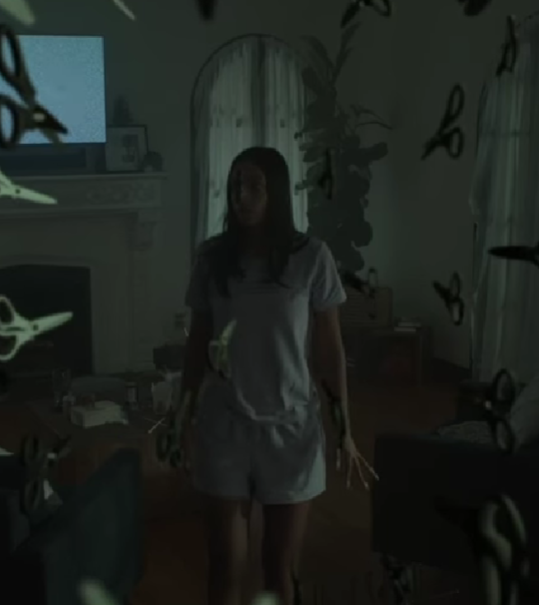

Now that the fourth wall is completely broken, the woman does not hold back, telling the audience and camera to leave as they have no story to tell. “We are just two ordinary people in the middle of a storm.” The couple becomes separated as they are transported to separate rooms, enacting the horror movie cliche of a couple’s separation. Lupkin’s critical essay refers to the cliche horror tropes apparent in this film such as this one. I agree that “when characters get separated”, it can “ heighten suspense” as part of the “mechanism that makes a good horror movie” and adds to the comedic element. The woman is furious with her situation and being forced into the plot of a horror movie.

She is bombarded with subtitles and forced into a classic horror filter. She decides to turn the tables and pursue the monster herself. She calls the viewers out for watching them and asks what they want from them; she exposes the viewers as monsters for being complicit with their treatment and taking joy from her pain. She tries to escape her fate and avoid picking up the scissors, but they surround her, leaving her no choice. In an ironic twist the scissors, which she grabbed to protect herself, led to the death of her lover. Satisfied with the pain caused and the story attained, the camera leaves the woman to her suffering.

The whole film was planned from the start. The director’s seeds were planted and the couple played into his hands. The film started at night as film needs to develop in the dark. The camera was the director watching the whole process along with his viewers. The scissors were used to cut the film the way he wanted. The director was in control even when the girl tried to escape and grab the doorknob, controlling the shutters of the camera and exposing the film to light; her every effort was stopped. In a way, this meta film was self-destructive. The director characterized themselves as the villain and villainized the whole horror genre as a result. Horror movies are enjoyed by the audience, but when it is over-analyzed, the genre loses its allure and purity when it is realized that it is essentially making fun of people dying and their pain. This is why going meta can be dangerous, as it can lead to an interesting plot, but can puncture the illusion killing the genre and turn the horror onto yourself.