Clocks are an invention; there is more to time than seconds

by Bryce Keslin

Daniel Zvereff’s short animated film Life Is a Particle, Time Is a Wave poses a time-honored question: what is time? At its most simple, the film is about an elderly widowed watchmaker who reminisces about his wife, seems to die, but wakes up in a hospital with a new lease on life. However, Zvereff uses this watchmaker to meditate cinematically on the nature of time, with music playing a crucial role.

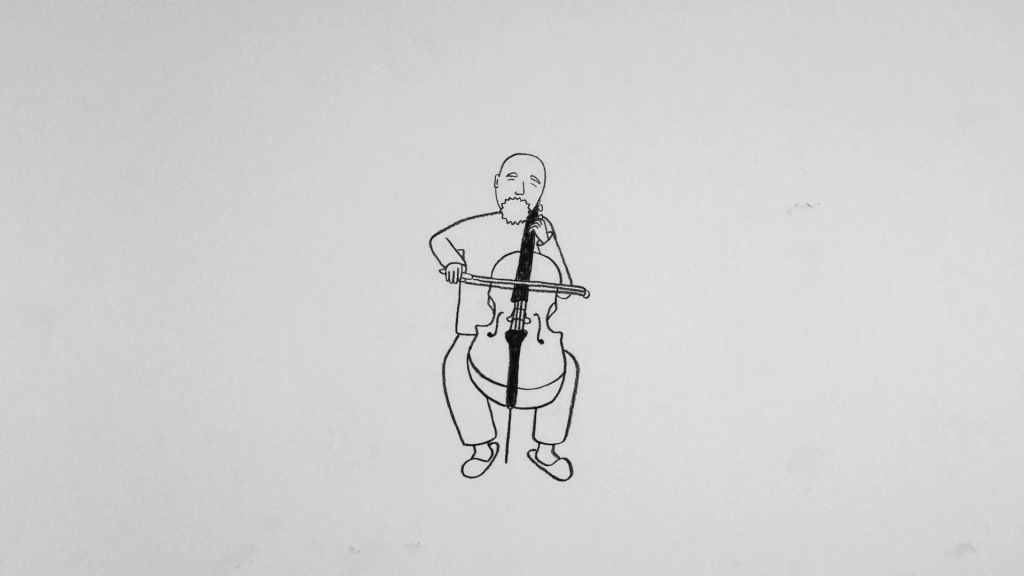

We first encounter the old watchmaker on oxygen restoring the tick in a watch. We see the first image of a cat clock with oscillating, ticking eyes. The man then starts background music on his record player. We see a fly eaten by a Venus flytrap and follow the old man through menial tasks. He then reminisces on a picture of his wife, remembering the day she died. The scene cuts to the man writing music notes and playing his cello. Then, a timelapse of the man completing menial tasks and taking pills every day occurs. The man smokes, even on oxygen. He goes to write more music, but his pencil breaks, while simultaneously having a heart attack. The ticking stops.

The second section flashes many disturbing images while following the man’s thoughts while he appears to be dead: eyeballs, living cells, and abstract drawings. Eyes dart around in an empty, echoing void. Here the music takes on the air of a sci-fi sound. More unsettling images follow: a fetus transforming into an adult and back to dust. The man is pictured with the cat’s eyes and then clocks for eyes. Eventually, the old man sinks into a liquid void, following his wife. The screen fades to black, leaving only the sound of a heartbeat and a monitor.

The last section of the film begins with the man waking up in the hospital. He returns home and can only stare blankly at the routine tasks he busied himself with before. The cat clock ticks one again. He takes the picture of his wife and while cleaning it, the venus flytrap opens with just a small ball of what formerly was the fly. He crumbles the tiny ball between his fingers. Euphoric music takes over. He then sits back down with his score paper, sharpens his pencil, and connects the notes. Finally, he picks up his cello and the ticking stops. He smiles, and plays a long sustained note. The ticking returns as the credits roll.

At first glance, all these images seem both ordinary and random: a relationship, a profession, an illness, a fly. What could these concepts possibly have in common? To answer this question, we must first look at the title, Life Is a Particle, Time Is a Wave. What does it mean, and how does it relate to the story of the watchmaker?

Not surprisingly, Zvereff represents time in relation to life. In Silvana Dunat’s article on Time Metaphors in Film, she concludes that by manipulating time, films invite audiences to reflect on philosophical questions about existence and the nature of reality. Zvereff masterfully uses the manipulation of time in this film to get the audience asking: What is life, and what is time? The life of one person is made of many instances, or “particles.” According to Merriam-Webster, a particle is “a relatively small or the smallest discrete portion of something.” Every second of our lifetime represents the many particles that make it up. Therefore, our lifetime can be counted by the seconds on a clock. However, clock time runs out eventually. Life as a particle symbolizes how we experience life as a series of discrete events and choices that eventually end.

Time, however, encompasses a wave of many moments. In Céline Roustan’s critical essay of the film, she quotes Zvereff saying, “clock time is an invented idea, and that time, that force that brings us ever closer to death is a more complicated and fluid concept – more like a wave than a ticking clock.” Time as a wave symbolizes how we experience time in our lives as a dynamic progression of highs and lows, with moments of stillness and moments of rapid growth. We look back on our lives not at the particular instances, but at the overall moments that define us. The images shown in the film; a relationship, a profession, an illness; represent moments in one’s life. The fly being eaten, turned into a ball, and rubbed into tiny particles, represents the meaningless in the particles of life compared to the moments of time.

This dual concept of time originates from the ancient Greeks. As Mckinley Valentine describes in her article defining the terms, they had two words for time: chronos and kairos. Chronos is chronological time. Kairos, however, represents moments in time. These terms can be applied to not just life as a particle and time as a wave, but directly to the watchmaker himself. It is vital to the story that the man is not just a watchmaker, but a musician. His watchmaker profession represents the chronos, mechanical time of his life. Adversely, his musicianship represents kairos, where time is fulfilled. In the first section of the film, the man is able to fix the watch, but unable to finish his score, due to a broken pencil. However, in the final section, he puts away the watches and finishes his score. By staring death in the face and seeing what mattered to him most (his wife, the kairos), the old watchmaker realized how narrow his view on time was, and how little of it he had left. In order to live the rest of his chronos time to the fullest, he realized he must create moments of kairos. He goes about this through playing music.

Music as an aesthetic means suspends clock time. It sutures moments in time together to create a beautiful life full of meaning. The watchmaker creates seconds, whereas the timemaker creates moments. Zvereff argues aesthetically that musicians are timemakers. Time seems to expand in music, lasting much longer than the clock claims. At the closing frames of the film, the old watchmaker takes ownership of the rest of his days, by composing the score of his life. He now knows: Time is not defined by the seconds of the chronometer, but by the moments of lived experience.