How horror films rely on audience identification to conjure discomfort and fear

by Alicia Melotik

In the 8-minute meta-horror short film Storm, a couple wakes one dark and stormy night to the sudden slamming of their door and finds themselves trapped within all of the typical tropes of a horror film. Isabel and Malcolm are aware of their place as characters in a movie and recognize the camera watching them but are nonetheless subject to being manipulated by its power. Directed by Lena Tsodykovskaya, the film includes the audience as a character via the camera’s POV to produce a sense of uneasiness and guilt at causing the characters’ distress.

The film’s visual track consistently follows standard horror tropes like Chelsea Lupkin describes: a slo-mo as they run for the exit, the characters getting separated for “no apparent reason” other than to add tension, the scissors becoming “both a tool for survival and the cause of another’s demise”. Additionally, the clichéd horror soundtrack motivates the characters’ actions, drawing them and the audience deeper into the suspense. In the opening pan across the bedroom (the above audio), low, ominous horns and thunder contrasted by gratingly high strings create an atmosphere of tension typical to the horror genre. To begin the film’s action, the sound of a creaky door closing jolts Isabel awake. Horror films often rely on invisible threats and the fear of the unknown to generate uneasiness. Accordingly, the mysterious knocking and yelling without a visual counterpart to “de-acousmatize” the sound heightens the discomfort for both the characters and the film viewers, since neither know what causes the sounds.

While the film purposefully follows many horror tropes, it is set apart from a typical horror movie once Isabel shines her flashlight directly at us, the audience, to expose the threat. Breaking the fourth wall while dissonant strings crescendo, Isabel looks and yells directly at the camera. This leaves us in an uncomfortable position and establishes the camera’s role as a character in the film. Since we share the camera’s perspective by the nature of the medium, we identify with it. In return, we are being identified with its actions-meaning we are to blame for threatening the characters. We feel responsible for the camera’s actions: how it scares the couple and separates them for just long enough until Malcolm gets stabbed by Isabel. Moreover, we are exposed for our sadistic viewing of the film.

As Tsodykovskaya states, “when watching Storm on a big screen, I did feel uncomfortable, as if caught red-handed, which has always been my goal”. By singling out the camera and thereby the viewer as the threat to the couple, we feel like we are the ones perpetuating their misery and are to blame for their pain. A sense of guilt is evoked as we realize they are living through these horrific tropes because of something we did-because we want to watch.

Why do we derive entertainment from watching these characters suffer? When watching horror films, we as the audience observe at a safe distance, unable to be touched or harmed. The soundtrack provides a layer of separation through non-diegetic music, differentiating our world from that of the film. Thus, we are left as an outside observer, free to indulge in the guilty pleasure of watching something intriguingly taboo. We don’t need to help the characters nor fear for their safety (since we know they aren’t real), so we take pleasure in voyeuristically watching their pain without them knowing we’re observing. However, like Kord describes, “forcing us into the killer’s perspective invites us to enjoy the violence, which – if we do – makes us feel guilty”. When we find amusement in the spectacle of horror, we then feel guilt for enjoying “the destruction of another human being” since that enjoyment presumably misaligns with our morals.

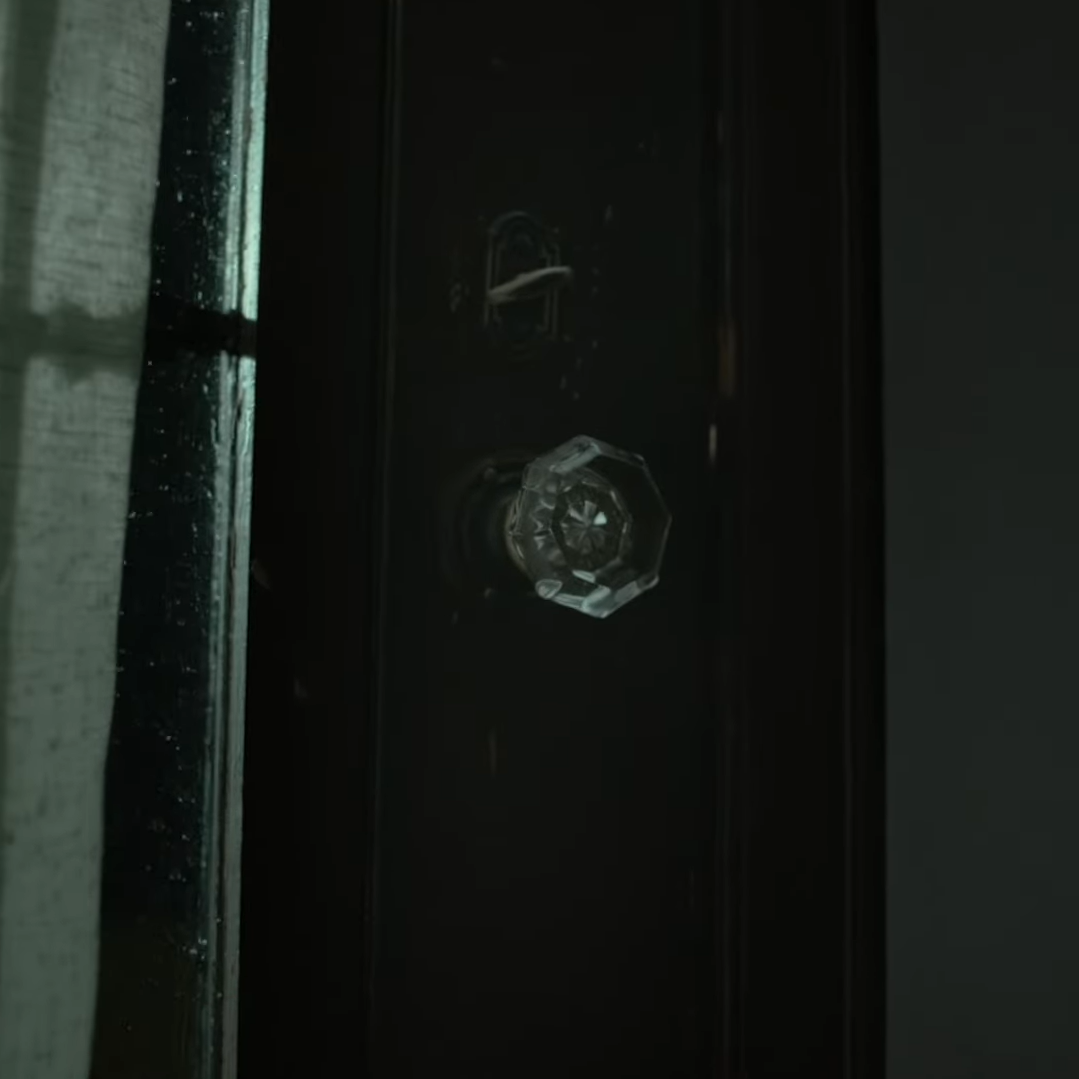

Furthermore, the camera (and the audience) isn’t just what terrorizes the characters: it is also their escape from the horrific night. As Isabel and Malcolm run towards the door to flee from their tormentor, we seem to see the first reverse shot of the film in which the villain is revealed. We see a shot of the door, and more specifically, the doorknob that resembles a camera’s shutter. Once Isabel reaches to open the door, the villain that is the film plays another trick on her, transporting her and Malcolm to rooms separated by a locked door.

As previously established, the audience and the camera act as one character in the film which plays its part in threatening the couple. Now, the camera (and the audience along with it) is further developed into acting as a doorway for the characters to enter and escape the film through. As an additional meta element of the film, Isabel ends up cutting Malcolm with the scissors when she meant to “cut the camera” and end the life of the film.

The film’s action begins with a door somehow closing, likely by the doing of the film, which alarms Isabel. Right after the door closes and Isabel awakens with a gasp, a short, ascending melody is played to convey that the film’s tension is beginning to rise as well. The film then ends the same as its beginning, indicating that they are stuck within the film so long as the audience chooses to watch them suffer. Each time we play the film, they relive the horror again and again. As long as we give into our voyeuristic impulse and the guilty pleasure of watching the couple, they will suffer. We are the escape: we can let them out of this horror movie by pausing or closing the video, but we choose to pull them away from the door and watch the film again. We force them to suffer for our own pleasure.