An Ode to Mothers Everywhere

By Grace Mazurek

One of my favorite study snacks lately has been pistachios – a taste I acquired from my mother. But little did I know that there was more about pistachios connecting me and my mom. Eating pistachios—not the shelled ones—means struggling to crack them open. In his short film Open, Richard Paris Wilson dives into this challenge and its maternal meaning.

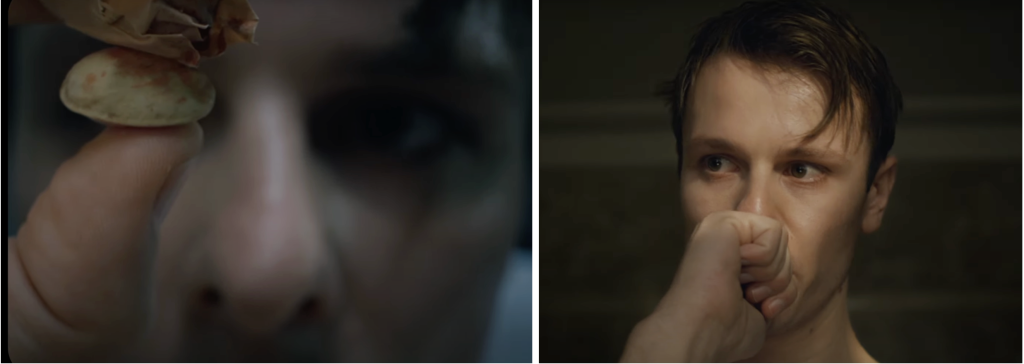

In Open, a young man eating pistachios becomes consumed with trying to open one that seems to resist. After failing using his fingers, he turns to every resource possible – hammers, chainsaws, golf clubs – but still fails, destroying his room in the process. The film begins without music, but is filled with the sounds of pistachios and efforts to crack them open. If the clicking and scraping of pistachio shells sounds like “nails on a chalkboard,” “nails on a pistachio shell” sets up the story to be about more than nut cracking, especially if it bloodies one’s fingertips. Something else is afoot. Indeed, a simple sad piano tune enters as the man tries harder and harder to open this one pistachio, refusing to move on to the millions of other pistachios at his disposal. The music suggests that the pistachio obsession is not just fun and games but something more. A violin joins suggesting a second element in the story. The man looks at his pistachio, wraps his hand around it, and kisses it. That pistachio is more than a pistachio, it’s a source of pain and the object of desire.

But why is this pistachio so hard to open? It turns out that pistachios have one of the hardest shells of all nuts. In an experiment ran by the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, it was found that pistachios “are encased in an ‘ingenious’ microscopic structure of interlocking cells so tightly bound, they never let go of each other” (link). Because of this, “they can take the energy of an impact and, by bending or stretching instead of breaking, redirect it away from the object to be protected” (link). It is literally built into the pistachio shell’s DNA to protect. The shell protects its seed, like a good parent protects their offspring. To the man, this relentless protection of the pistachio is a reminder of this parent.

The film’s pistachio parent symbolism becomes kafkaesque when the bittersweet piano and violin duo gives way to drums and electronic sounds as the man gets more aggressive with his attempts to open the pistachio. When he hits the pistachio with a golf club, mickey mousing (musical sound effects mirroring the movement) suggests a cartoonish grotesqueness. Wilson likely got inspiration from the early 20th-century author Franz Kafka whose stories explore alienation, bureaucracy, absurdity, and existential dread, often featuring characters trapped in surreal, oppressive, and nightmarish situations. Viewers who know that Wilson’s film parallels Kafka’s stories have an insider view to the pain that this excessive longing can cause.

Indeed, in the following bathtub dream sequence, scored with slightly off-putting music, the man wakes up in a tub full of pistachios, and then goes wild, searching for his pistachio. He eventually finds it and clutches it to his heart. As this occurs, an eerie song with gongs, bird songs, and chimes plays, eventually turning into a lullaby, but one played by electronic instruments. This music combines both peaceful and chilling sounds, calling back to the good memories from the parent the pistachio represents, and to the uncertain future without the parent, no longer accessible. The good (memories and experiences with those we love) cannot occur without the bad (those we love leaving) eventually occurring.

Throughout the film, the man’s phone has been buzzing with texts from his sister, but obsessed with the pistachio, he ignores it. Yet at the end, the man cannot ignore the news anymore, as his sister (dressed in funeral black) physically comes to him to comfort him. The man is forced to face the bad occuring, which we learn is death.

We learn the specific answer to who has died and why this pistachio is so special when the man’s pistachio frenzy results in him imagining a giant pistachio imitating his mother’s womb. Angelic music plays, beckoning him to the womb, in which he curls up in. Just as the man is trying to get this one pistachio open, he is trying to get his (now dead) mother back.

But this angelic chanting music is not just angelic. It soon morphs into more of a demonic chanting music, sounding like screeching instead of calling. This change of music directly reflects the genre of dark comedy that Open is. Not only is this at first light-hearted film actually about a deep topic of losing who you love, but this demonic music warns of the agony that can happen if you try too hard to go back to what is lost. Physically, this was represented by the occurrence of blood after too many tries of opening the pistachio.

The pistachio protects its seed too firmly. This never ending protection is one of the best definitions of a mother’s love. Just like the physical properties of the pistachio shell, a mother will grab on to her children so tightly and do her best to protect them from harm and never let them go. In this film, the young man is trying to cling to this feeling of love he will never (at least so obviously) be able to feel again. Next time you eat a pistachio, remember to acknowledge what you have when you have it, and to feel the love surrounding you. Thank your mother or motherly character in your life today, and perhaps offer her a pistachio and a story.