How Sound Can Put Us Into the Driver’s Seat

By Ben Warren Flynn

Traditional film music creates atmosphere, evokes emotions, and guides the audience’s perceptions. It can also underscore the psychological states of characters and help build a world around them. Such is the case in Santiago Menghini’s 2024 animated sci-fi short Rally. Sound plays a central role in constructing its gritty and immersive environment. However, it does so in a unique and significant way that strikes a middle-ground between cinematic realism and the game-like elements of the film.

Set in a grim dystopian world, the film follows two underground smugglers tasked with transporting a hostage across a contested border in a modified rally car. The smugglers race through hostile terrain and withstand surprise attacks before arriving at their destination. From the roar of the car’s engine to poignant silences, every auditory detail assists the real-time animation—created by the director with the Unity game engine—to make the game-like environment feel authentic.

The soundscape first invokes the natural: a thunderous storm and heavy rain whose crisp rumble and torrential droplets sonically soak us in the dark, cold outdoors. Suddenly, the rainfall is muffled and we are inside the car, directing our ears to mechanical and electronic sounds. A watch ticks in anticipation and a sombre voice transmits a radio message, as if warning of impending doom. The driver is breathing through a helmet – not unlike Star Wars’ Darth Vader. We are in sci-fi territory now.

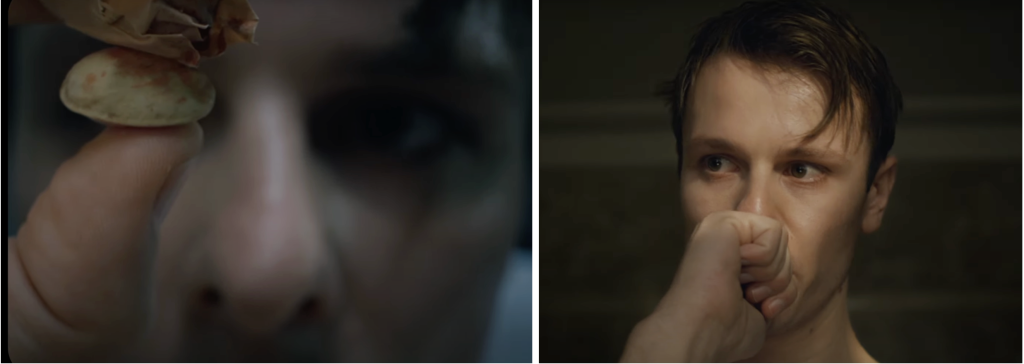

Two striking shots are juxtaposed: the face of the driver’s watch and his face, the latter revealing that this is a real-time animation short. The aesthetic realism is noticeably artificial, harkening back to beloved animated video games. The camera alternates between the driver’s point of view and third person shots of him. This juxtaposition positions us between seeing and seeing someone seeing. Are we the driver (as in a video game), or are we simply watching him driving (as in a film)? For Julianne Grasso, a researcher of video game music, such slippage falls on a ludonarrative spectrum, with “ludic” games emphasising interactivity — explorable landscapes, inhabitable avatars, agency over events, and embedded challenges — while narrative structures are closer to a non-interactive, cinematic observation, with pre-designed plot and characters. Though a film, viewers experience Rally like a game, an explorable reality simulating their position in the driver’s seat.

Sound effects insert us as avatars in the plot. As black vans approach with a menacing growl and open the rally car’s trunk, we are present. The trunk door opens like a spacecraft, with an airy whoosh as it glides up. The hostage is thrown into the car with a few hollow metallic thuds and the trunk swooshes closed again with a soft click. This world is futuristic.

While invoking a video game nostalgia, Menghini reminds us that we are still in the world of narrative film through music. The scoring is central to bridging the gap between the two artforms. It is cinematic yet immersive. One instrument sticks out in the mix. The flute is the only named instrument in the end credits. While its inclusion may at first be perplexing, it is a core ingredient to the creation of character in this short. The flute attaches itself to the smugglers throughout the film, particularly the driver, through its melodic interjections. It is heard at key moments such as the beginning of the journey and the arrival at the border. It is centred around the driver, flowing with his accelerations and decelerations. When his fellow smuggler is shot, the flute disappears and our focus is drawn to his heavy breathing as he escapes danger.

But why is the flute the driver’s inner soundtrack? The choice becomes clear when we consider his stressed breathing. The emphasis on his breath, despite its distorted timbre, highlights his humanity. Although his environment is artificial and robotic, he is a real person. The flute reinforces this in ways that an electronic instrument could not. It is the result of human breath. His music serves as a division between his existence and his circumstances.

Rally’s finale replaces the flute with an organ; human breath is replaced by a mechanical pipe. The systematic drudgery that this dystopian future has imposed on the driver is heard in the funeral-like scoring. His instrument is silenced and he is distanced from the action, as are we. Experience and immersion are traded for observation and message, and the authorial view comes to the forefront. Both the organ’s lament and beeping watch signify the end for the driver. There is hope that he will put an end to his smuggling days. His undeniably human reaction to losing his partner proves he feels empathy and likely resents his work. However if the corrupt system we have seen throughout the film pervades, it is possible that he will never escape this harrowing lifestyle, and the ghostly hymn signifies his inescapable doom.

Rally is a reminder of recent feature films that capitalise on the game-like experience, such as Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver. This film, like Rally, is centred around the car chase as a means of driving narrative. While it doesn’t put us directly in Baby’s POV, the film is an immersive experience that highlights him as “the avatar” through his music — not through the music itself but rather his deliberate decision to play it. Similarly, the flute is the driver’s music in Rally. By experiencing the music heard by these two “avatars,” we are inhabiting them like video-game characters, while also seeing human aspects of their existence. The latter keeps us grounded in the realm of film. Rally ultimately blurs the lines between cinema and gaming, using sound and music to create an immersive yet emotionally resonant experience that underscores the humanity within its dystopian narrative.