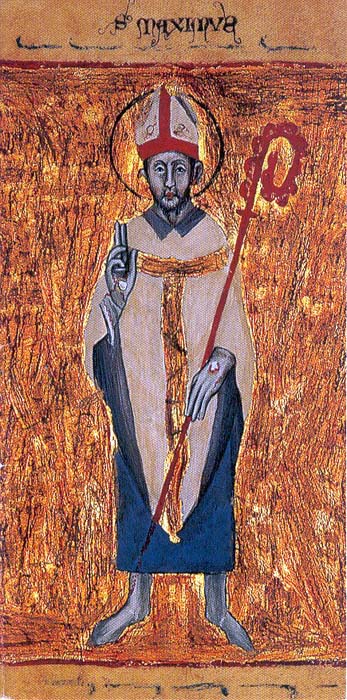

For introduction and contextualization of my transcription and translation of this Easter homily by Maximus of Turin in its manuscript context (Ambrosiana MS B44 Inferiore), see my translator’s preface.

Modern English Translation by Mihow McKenny

Note: The below translation is based on a comparison of my transcription from Ambrosiana MS B44 Inferiore with the modern edition by A. Mutzenbecher.[1]The transcription does not differ in any substantial way from the edited version; differences are noted in the footnotes.

1 The fables of the world tell of that Ulysses who, thrown about by errant seas for ten years, was unable to reach his homeland when the course of his navigation pushed him into a certain place, in which the seductive song of the sirens was resounding with cruel sweetness and the approaching ones were so soothed by the deceptive melody that they did not seize the spectacle of pleasure as greatly as they risked the shipwreck of their safety. For such was the delightfulness of the song that whoever heard the sound of its melody would—as if captured by a certain hex—no longer tend toward the port which he desired, but would hasten toward a death which he did not wish. Therefore when Ulysses fell upon this sweet shipwreck and wished to avoid the danger of its seduction, with wax having been inserted in the ears of his companions, he is said to have bound himself to the mast, where the charming, pernicious sounds were absent even for him, and where the course of the ship could protect him from danger.[2]

2 If, therefore, the story of that Ulysses tells that his binding to the wood freed him from danger, how much more widely should that which has been truly done be preached; namely, that today the wood of the cross snatches the human race from the danger of death! For on account of this, that Christ the Lord was hanged on the cross, do we pass through the charming perils of the world as if with our eyes closed. For we are not detained by the world’s dangerous sound nor are we thrown from the path of a superior life into the rocks of pleasure. Further, the wood of the cross not only represents man’s self-crucifixion onto his homeland: the wood also protects those who stand nearby it, through the shadow of its virtue. That the cross, after many wanderings, allows us to return to our homeland, this the Lord declares, saying to the thief on the cross “Today you will be with me in paradise.”[3] The thief, who was long a wanderer and shipwrecked (differently), would certainly have not been able to return to the homeland of paradise, from which the first man departed, unless he had been bound to a tree. And a certain tree on the ship is a cross in the Church, which alone is preserved safe among the sweet and dangerous shipwrecks of all the world. Therefore, whoever upon this ship binds himself to the wood of the cross or closes his ears with the Divine Scriptures will not fear the sweet storm of lust. For that sweet figure of the sirens is a charming desire of pleasures, which with noxious blandishments makes feminine the constancy of the captured mind.

3 Consequently Christ the Lord hung on the cross, so that he might free the entire human race from the shipwreck of the world. But in order that we may pass over the tale of Ulysses, which is fictive and not factual, let us see if we can find a similar example in the Divine Scriptures, which contain what the Lord had earlier made known through his prophets, and what he would later fulfill through himself. We read in the Old Testament that when holy Moses led the sons of Israel from the captivity of Egypt, and when that people was in distress because of a grave incursion of serpents—against which it could not defend itself by any weapon—saintly Moses, filled with the divine spirit, erected a bronze serpent attached to a wooden staff in the midst of the dying crowds, and ordered the people to derive from this wood the hope of health. And from this sign such a medicine against the snake-bite was provided, that whoever looked upon or hoped in the cross of the serpent immediately received a restoration of health. The Lord recalls this deed in the Gospel, saying, “As Moses raised up the serpent in the desert, thus must the Son of Man be raised up.”[4] Whence if the serpent fixed to the wood brought health to the sons of Israel, how much greater health does the Lord, crucified on the yoke, proffer to the people! If the figure brought so great a profit, we believe the reality to offer even more.

4 The serpent, therefore, is crucified first; and it is right that the devil, who first sinned before God, might be the first one smited by the sentence of the cross. And fittingly he is crucified on wood so that, since man was deceived in paradise by the tree of desire, he might now be saved by the same tree of wood; and the matter which was the cause of death might be the remedy of health. Thereafter, following the serpent, man himself is crucified in the savior—this is done so that after its author, the crime may also be punished. By the first cross the crime is avenged against the serpent; by the second—in the venom of the serpent—the crime’s originator is himself punished, since his malignity is condemned. The virus which by his persuasion passed into man is now cast out and cured. For when man abandons himself to lust, he is not given up to death, but the sin in him is atoned; this the Lord achieved by the man whom he took up, so that the disobedience of diabolic duplicity could be corrected in Him while He innocently suffered, and so that afterwards man might become free from guilt, as well as free from death.

5 Therefore having our Lord Jesus, who freed us by his suffering, we should always gaze upon Him and from his very sign we should trust in the remedy for our wounds—if, by chance, the venom of avarice spreads itself in us, let us think of Him and He will heal us; if the lust of the scorpion stings us, let us beg Him and He will cure us; if the bite of earthly thoughts cuts us, let us cry to Him and we will live. These, then, are the spiritual serpents of our souls, for the destruction of which our Lord was crucified, and regarding which He says “Over serpents and scorpions you shall walk, and nothing shall injure you.”[5]

Transcription from Ambrosiana MS B44 Inferiore

1 Seculi ferunt fabule ulixem illum qui decennio marinis iactatus erroribus ad patriam pervenire non poterat cum in locu quendam cursus illum navigii detulisset in quo sirenarum dulcis cantus crudeli a varietate[6] resonabat et advenientes sic blanda modulatione mulcebant ut non tam spectaculum voluptatis caperent quam naufragium salutis incurrerent. Talis enim erat illis ablectatio cantilene ut quisquis audisset vocis sonitum quas quadim captus, illecebra non iam tenderet ad eum quem volebat portum, sed pergeret ad exitium quod nollebat. Igitur cum ulixes incidisset hoc dulce naufragius et suavitatis illius vellet declinare periculum dicitur inserta cera auribus sociorum se religasse quo et illi carerent pernitiosa auditus inlecebra et se de periculo navigi cursus auferret.

2 Si ergo de ulixe illo referit fabula quod cum arboris religatio de periculo liberaret, quantomagis predicandum est quod vere factum est, hoc est quod hodie omne genus hominum de mortis periculo crucis arbor eripuit. Ex quo enim Christus dominus religatus in cruce est, ex quo nos mundi inlecebros discrimina velut clausa aure transimus. Nec perniciosa seculi detinemur auditu, nec cursum melioris vite deflectimur in scopulos voluptatis. Crucis enim arbor non solum religatum sibi hominem patrie representat, sed etiam socios circa se positos virtutis sue umbra custodit. Quod autem crux ad patriam post multos errores redire nos faciat Dominus declarat dicens latroni in cruce posito: “Hodie mecum eris in paradiso.”[7] Qui utique latro diu oberrans ac naufragus aliter ad patriam paradisi de qua primus homo exierat redire non poterat nisi fuisset arbori religatus. Arbor enim quedam in navi est crux in ecclesia que inter totius seculi blanda et pernitiosa naufragia incollumis sola servatur. In hac ergo navi quisquis aut arbori crucis se religaverit aut aures suas scripturis divinis clauserit, dulcem procellam[8] non timebit. Syrenarum enim quedam suavis figura est mollis concupiscentia voluptatum que noxiis blandimentis constantiam capte mentis effeminat.

3 Ergo dominus Jesus[9] pependit in cruce ut omne genus hominum de mundi naufragio liberaret. Sed ut omitta[10] ulixis fabula que ficta est[11] videamur si quod in scripturis divinis exemplum simile possumus invenire: quod Dominus per semetipsum postea completurus per prophetas suos ante premiserit. Legimus in veteri testamento cum Moyses sanctus filios Israelis de captivitate egipti perduxisset, atque idem populis in deserto gravi a serpentibus incursione laboraret, nec aliqua illis armorum defensio possit obsistere, tunc sanctus Moyses divino repletus spiritu serpentem aureum adfixum ligno inter medias morientium erexisse turbas et mandasse populo ut de illo ligno spem gererent sanitatis, atque hac re tantam medicinam contra morsum aspicum provenisse, ut quisquis vulneratus in illam serpentis crucem aut respiceret aut speraret statim remedium salutis acciperet. Cuius facti etiam dominus in evangelio meminit “Sicut Moyses exaltavit serpente in deserto ita exaltari oportet filium hominis.”[12] Unde si adfixus serpens ligno filiis Israel contulit sanitatem quantomagis salutem prestat populis Dominus in patibulo crucifixus. Et si figura tantum profuit quantum prodeese credimus veritatem.

4 Serpens igitur primus crucifigitur recte plane ut quia primus apud domini[13] peccaverat diabolus primus crucis sententia servetur.[14] In ligno enim crucifigitur rationabiliter factum[15] ut quia homo in paradiso per arborem concupiscentie deceptus fuerat nunc idem per ligni arborem salvaretur atque eadem materia que causa mortis fuerat esset remedium sanitatis. Deinde post serpentem in salvatorem homo ipse crucifigitur scilicet ut post auctorem puniatur et facinus. Per primam enim crucem vindicatum est in serpentem per secundam[16] venena serpentis. Hoc est primum auctor ipse punitum deinde eius malignitas condempnata (est)[17]. Virus enim quod persuasione sua in homine transfuderat nunc reicitur nunc curatur. Nam cum homo passioni addicitur non morti traditur sed mortis in eo facinus emendatur. Hoc enim egit dominus per hominem quem suscipit ut dum innocens patitur prevaricationis illius diabolice in eo inobedientia corrigatur, et deinceps libera culpa fieret ac liber esset a morte.

5 Habentes igitur dominum Jesum qui nos passione sua liberavit, in ipsum aspiciamus semper et[18] ipsius signo speramus[19] nostris vulneribus medicinam. Hoc est si forte nobis venenum avaritie sue[20] diffundit, in ipsum consideremus et sanat; si scorpionis nos libido conpungit ipsum rogemus et curat; si terrenarum cogitationum nos morsus lacerat, eundem precemur et vivimus. Huius[21] enim sunt spiritales serpentes animarum nostrarum propter quos conculcandos dominus crucifixus est de quibus ipse ait “Super serpentes et scorpiones ambulabitis et nichil vos nocebunt.”[22]

Mihow McKenny

PhD Candidate in History

University of Notre Dame

[1] Maximus of Turin, Sermo XXXVII,in Maximi episcopi taurinensis sermones, ed.A. Mutzenbecher, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 23 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1962).

[2] Odyssey, bk. 12

[3] Luke 23:43.

[4] John 3:14.

[5] Luke 10:19.

[6] suavitate (Mutzenbecher, hereafter “M”)

[7] Luke 23:43.

[8] procellam luxuriae (M)

[9] Christus (M)

[10] ommitamus (M)

[11] ficta non facta (M)

[12] John 3:14.

[13] Deum (M)

[14] feriretur (M)

[15] factum est (M)

[16] secundam in (M)

[17] condemnatur (M)

[18] et ex (M)

[19] speremus (M)

[20] se (M)

[21] Hii (M)

[22] Luke 10:19.