By Abigail Shelton and Jon Hartzler

What if you could compare a Rembrandt van Rijn print of David and Goliath held at the Snite Museum of Art in South Bend, IN, with the same print at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., online, at any time of day?

Or, zoom in so close that you could see the paint texture on this Vincent Van Gogh self-portrait hanging across the country at the Harvard Art Museum?

The answer is that you can! With the help of an open-source image sharing system called IIIF or the International Image Interoperability Framework.

This set of specifications, pronounced triple-eye-eff, provides a standardized way of storing and displaying images. This allows institutions using IIIF to easily share images. IIIF also has a suite of enhanced features that offers end-users a powerful research experience.

IIIF is at the heart of the Museums, Archives, Rare Books and Library Exploration (MARBLE) platform in development at the University of Notre Dame.

What is IIIF?

If you are new to IIIF, a helpful way to think about it might be the analogy of a travel adapter. A recent blog post written by museum developers describes IIIF technology in this way:

- Picture your preparations for an international trip.

- You gather all of your travel essentials and realize that you don’t know anything about the power outlets in your destination country.

- So, you look it up and find that they use the same outlet as you do at home.

- What a relief! No need to be concerned with bulky adaptors.

- You just know it will work—”it’s one less thing to worry about,” as stated in the aforementioned post.

Similarly, when libraries and museums use IIIF compatible images, it’s easier for developers and audiences to work with these images, both locally and across institutions. Developers don’t need to build custom “adaptors” because IIIF standardizes the way images are delivered and displayed. Users have a seamless viewing experience. Every time.

And now for a more technical explanation. The IIIF specification defines two application programming interfaces (APIs); one for image delivery and one for presentation. An API is a software program that allows information to transfer between applications.

The image delivery API provides a standardized way for web applications to pull images from where they are stored (server) to where they are displayed (website). This makes it easy to retrieve images in different sizes (thumbnail vs. full-size), different orientations (upside down), and different color scales (greyscale, black and white, color, etc.).

The presentation API provides a structure for how images are displayed online. It sets rules for how images are ordered (e.g. pages in book), and what information is presented to the user about the images (e.g. descriptive metadata). The presentation API is what allows developers to display images in IIIF compatible viewers (like Universal Viewer or Mirador) on a webpage.

The combination of these two API standards means that images can be easily used and reused in predictable and reliable ways. Developers no longer need to build highly customized applications for a diverse array of image formats. Or, in the travel analogy, no need for bulky adaptors for every new destination!

How is the University of Notre Dame using IIIF?

IIIF is at the heart of the MARBLE project. Our IIIF server is the primary way that images are presented to users through the website. The process works a little like this:

- Library and museum colleagues deposit their images in a Google Drive directory, along with metadata that describes what the image is and how it should be displayed.

- Once the deposit is complete, our open-source IIIF Pipeline automatically detects the new images and information and creates a IIIF compatible document (IIIF manifest). This document, full of standardized image metadata, allows us to use the same image in multiple ways, across multiple platforms, without duplicating our efforts.

For example, the IIIF document for Paul’s Wood’s Absolution Under Fire could be searchable in the MARBLE site, highlighted in a digital exhibit on the artist at Notre Dame, and featured in a specialized collection website highlighting all of the Civil War materials on campus. With IIIF, this can all happen at the same time, without the need to re-enter any metadata or copy any images.

Paul Henry Wood (American, 1872-1892), Absolution Under Fire, 1891, oil on canvas. Gift of the artist, 1976.057. Snite Museum of Art.

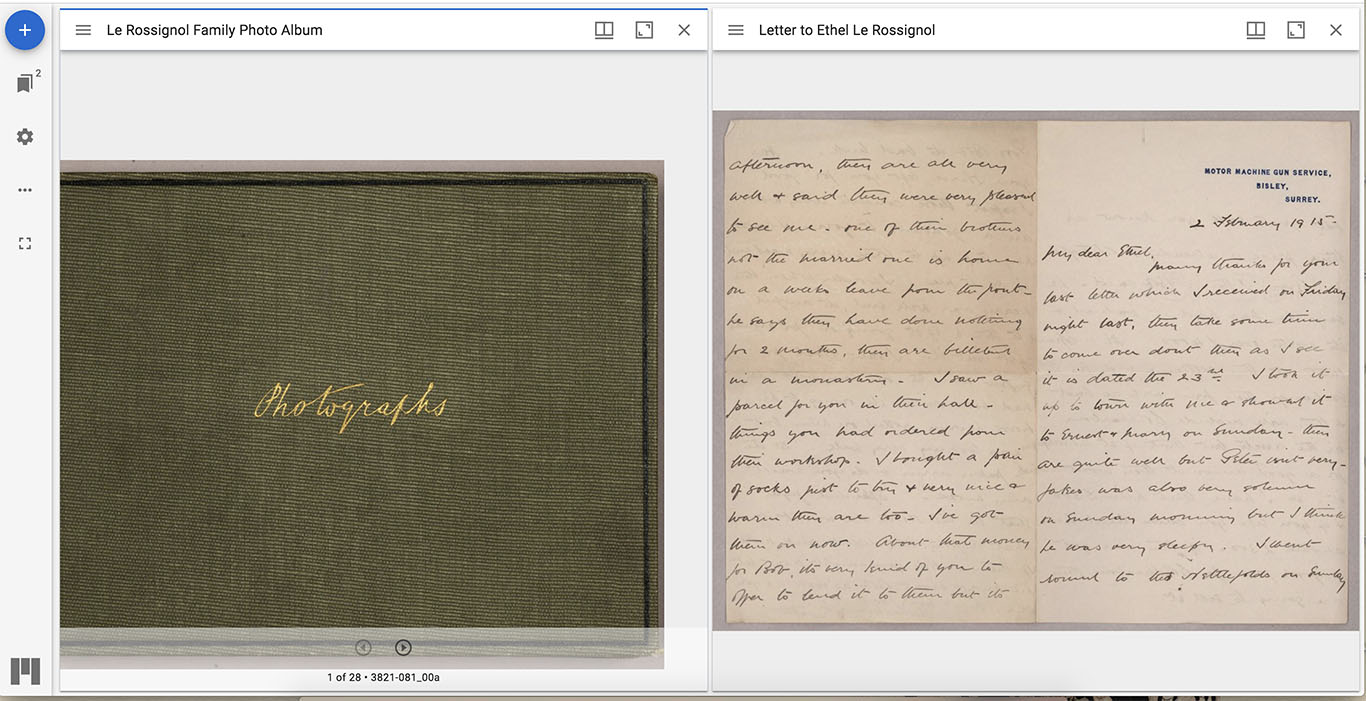

We’ve also embedded a IIIF image viewer called Mirador in the website to empower users to examine objects closely and compare them side-by-side. Ultimately, we’d also like to enable users to annotate images in the viewer and then save, search, and share those annotations for personal research or classroom uses.

Several of our staff are also involved in the IIIF international community, helping to spread the word and develop new features for this open-source software. IIIF is an open-source application meaning that there is a group of volunteers from institutions around the world contributing to its development. Notre Dame colleagues have attended the annual conference, regional working group meetings, and participate in regular community conference calls. Our involvement in the IIIF community means that we’re learning from our peers and bringing ideas back to campus for how to showcase our collections in creative ways.

What can I do with IIIF as a student, educator, scholar, practitioner, ________?

So glad you asked! When the MARBLE portal goes live in 2021, you’ll be able to use Notre Dame’s unique collections in a variety of ways, including:

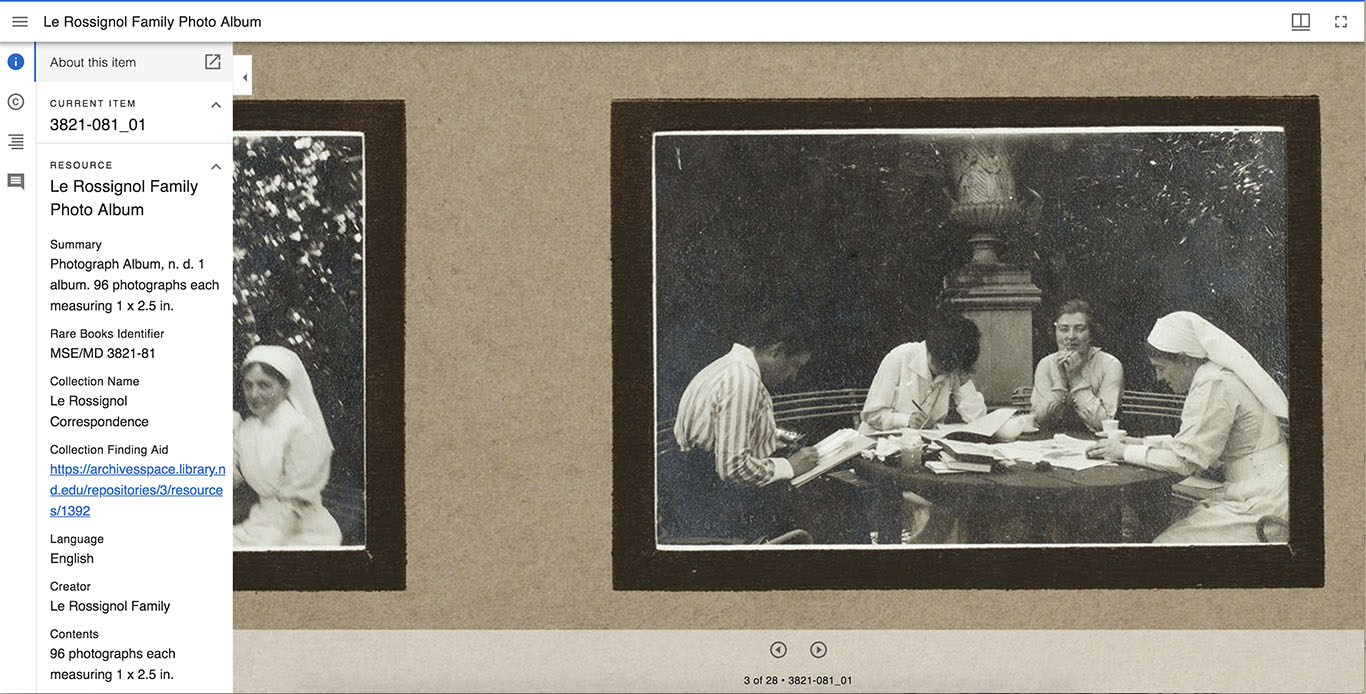

Detail of Le Rossignol Family Photo Album, Rare Books and Special Collections Department, Hesburgh Libraries, University of Notre Dame.

- You’ll be able to examine artworks and textual materials far closer than you could ever safely do in person.

- As an educator, you could project these images in your classroom to help students see details they may have missed during their museum or library visits.

- Students will be able to zoom into images while working on course assignments outside of open hours for the archives or museum.

- You will also be able to display multiple images side-by-side, either from the Notre Dame collections or from any other institution with IIIF compliant collections. This could allow you to compare details of multiple paintings by the same artist or read different versions of a text together.

- Using the same feature, you could digitally reunite collections of objects or even pages from libraries or museums around the world.

Le Rossignol Family Photo Album (leftside) next to a Letter to Ethel Le Rossignol (rightside) in Mirador viewer. Both from Rare Books and Special Collections Department, Hesburgh Libraries, University of Notre Dame.

Here’s an example project where four European libraries combined their early Qurʾānic fragments to recreate original codices using IIIF.

While IIIF opens up a myriad of possibilities for international collaboration, it will also allow us to reunite collections on our campus. For instance, the Snite Museum of Art’s current exhibition of Irish art features a number of broadsides, prints, and volumes from the Rare Books and Special Collections department alongside paintings and photographs from the museum collection.

The only way for audiences to see these objects together is to see the exhibition in person before it closes in December (strongly encouraged!). But what if these connections could be preserved? By making these materials available online in a IIIF compatible way, curators can maintain and highlight relationships between collections beyond the close of a special exhibition.

IIIF also powers fun! From art puzzles to Google Chrome plug-ins to mindfulness apps, the possibilities are endless. We’re excited to see how our users experiment with IIIF and create new ways of seeing and experiencing Notre Dame’s unique collections.