At the beginning of the 20th century, Notre Dame students, faculty, and administrators would often grumble about the Hill Street Car: overcrowding, aging equipment, erratic timetables, and rude conductors. The streetcar operators often complained of the students: overcrowding the cars, not paying fares, and playing pranks. In early February 1916, it all came to a head.

Caption: “Meeting the First Car, September 14, 1907”

Contemporary accounts vary on the details, but the following is a general outline of the incident: On the afternoon of February 3, 1916, a group of Notre Dame preparatory students locked the door on the conductor to prevent him from collecting fares. The motorman heard the commotion and asked a Carroll Hall (Main Building) preparatory student, who was about 15 years old, to pay his fare. As the student had already paid and wasn’t going to pay twice, he began to argue with the already irritated motorman. The motorman hit the boy with an iron switch hook and a collegiate student on board defended the younger student by hitting the motorman in the jaw.

That evening, the streetcar company added a few burly men to the line, presumably as a means of security. From the students’ point of view, these “hired thugs” were there to exact vengeance. On the way back to Notre Dame after a night downtown, a few Carrollites lit up cigars after the last woman disembarked the streetcar. While technically against the rules, this custom of smoking among passengers and employees had been honored for years, so long as no women were on board and the car was outside of city limits. However, this was enough for the streetcar muscle to bring the transgression to fisticuffs. One student reported that there were eight thugs, armed with revolvers and clubs, who took on teenage preparatory students.

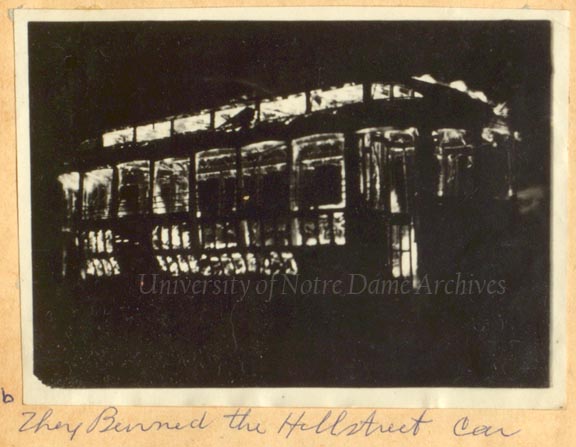

For the next few days, throngs of Notre Dame students packed the cars, looking for the men who beat up their fellow classmates. By Sunday, February 6, the students hadn’t found the culprits, so they decided to take vengeance on the car itself. A group of students hijacked a streetcar near Cedar Grove Cemetery on Notre Dame Avenue. They told the conductor and motorman to get off the car; and once it was empty, the crowd of about 150 students took to destroying the car and eventually setting it on fire.

University President John W. Cavanaugh and a few other priests happened to return to campus via automobile around 11 p.m. to find the Hill Street car surrounded by students. Cavanaugh recounts to Rev. John Talbot Smith that “a short distance from Egan’s we espied an immovable car gorgeously lighted and surrounded by a multitude of very happy students. As we approached, the boys, thinking we were the plug-uglies sent out to take care of the situation, fastened on us like hungry wolves, commanding the machine [automobile] to stop. Opening the door, I stepped lightly out and stood in the midst of them. Curtain; likewise curses. Oh, how those poor boys besought me to go on and not interfere with their labors!” [PNDP 30-St-16].

Father Cavanaugh told the boys to go back to their dorms and leave the streetcar alone. As things settled down and students started to disperse, Cavanaugh then continued on to the University by automobile; and once out of sight, the students continued on with their bonfire. Cavanaugh wrote, “I never thought to glance backward until I arrived at the University, when I found to my intense surprise that the students, seeing me pass by them with such child-like faith and innocence, had turned back and wrought their zeal upon the trolley. It made a beautiful fire and was the talk of the town and the subject of editorials, I regret to say, in many cities” [PNDP -30-St-16].

The South Bend fire department arrived on the scene, but high winds made it impossible to save the car. Police officers also responded to the situation, but only went as far as the city limits and no arrests were made. Tensions between Notre Dame and the car company were high for days in the aftermath of the fire. A mass meeting of the students was held in the Fieldhouse regarding the incident. Many, including the student body president, spoke against the destruction of the streetcar company. The streetcar company demanded that Notre Dame pay thousands of dollars for the damaged car. With both sides at serious fault, neither side pressed charges. The students had an advantage in that they could positively identify the “thugs,” but no student could be identified as the arsonists. The students, not the University, were ultimately liable for the property damage.

While many expected mass expulsions, Father Cavanaugh defended the Notre Dame students while also condemning their lawlessness. While usually severe in punishment on seemingly lighter situations, Cavanaugh felt that the students’ actions were inevitable after such provocations and that the students were right to seek justice, even though it be misguided and unlawful.

Officials from Notre Dame and the streetcar company met a few days after the fire to draw a truce. Both sides regretted the incident and vowed to work together to prevent such a disastrous breaking point. The student body agreed to behave in a civil manner, so long as the streetcar employees maintained a similar manner. The streetcar company also agreed to provide better service and newer equipment on one of its most profitable lines. Streetcar service to Notre Dame resumed shortly thereafter with no other notable incidents. Streetcars service in Michiana ended on June 15, 1940, when the line was replaced by a more economical bus line.

Sources:

Scholastic

Dome yearbook

Notre Dame: One Hundred Years by Rev. Arthur J. Hope

CNDS 7/29

PNDP 04-Di-01

PNDP 30-St-16

GKLI 2/17-20

GMIL 1/06

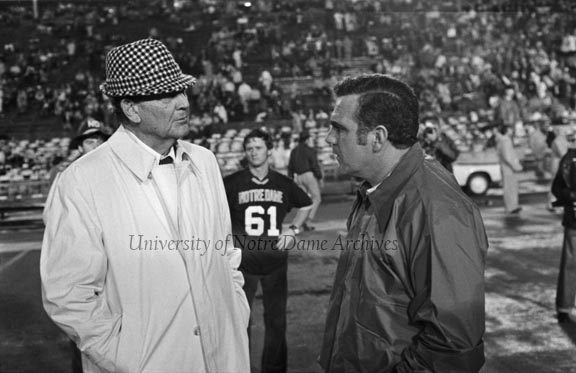

![Four students standing outside in winter with snow with a banner with a drawing of the Leprechaun and text that reads "Oh Alabama, don't you cry on me, the Irish'll roll the Crimson Tide way back to No. [number] 3" in regards to the 1973 Sugar Bowl football game, December 1973.](http://www.archives.nd.edu/about/news/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GDOM-11-02F-01.jpg)