On June 11, 1917, Notre Dame added a new demographic to its alumni base – women. According to Scholastic, the first two women to earn degrees from Notre Dame did not go unnoticed. During commencement, it was reported that “[t]here was an enthusiastic outburst of applause in Washington Hall when the names of Sister Francis Jerome and Sister Lucretia (Holy Cross Sisters of St. Mary’s College) were read out as recipients of the M.A. [Greek] and M.Sc. [Chemistry] degrees [respectively]” [Scholastic, September 29, 1917, page 6]. The graduation of these two women at Notre Dame was not a one-off occurrence, but rather marked the beginning of a historic tradition of coeducation at Notre Dame. Except for the 1919 commencement, women have graduated from Notre Dame every year since 1917.

The history of coeducation at Notre Dame is a fascinating and complex one. The view of Notre Dame as an all-male bastion often leaves out the story of Notre Dame’s female students who were here before their more traditional female counterparts moved in for the fall semester of 1972. A cursory overview of the commencement programs done in the 1980s gives us a glimpse of these pre-1972 women: 324 bachelor degrees, 4128 masters degrees, 184 PhDs, and 2 law degrees. However, these numbers only tell part of the story.

Going back through the commencement programs today, we gathered more personal information on these women to help humanize them. Many women studied at Notre Dame but did not complete their degrees. They, unfortunately, won’t be on this list, which was created to give a flavor of who these women were. It is for informational purposes only, not to be used as the sole source of serious research. Please contact the Registrar to verify student information.

At the time of this posting, we still have a ways to go to complete this list, but the data gathered thus far is quite interesting. Perhaps there are more laywomen in the mix than what people assumed. Sisters from Saint Mary’s comprise only a fraction of the other orders represented. Notre Dame’s female graduates follows the diversity of the general student population, with women represented from across the country and internationally, including Nova Scotia and the Philippines. The number of multiple degrees the women earned is a bit surprising, as was discovering two triple-Domers thus far: Sister Mary Aloysi Kerner (BA 1922; MA 1923; PhD 1930) and Sister Mary Jerome Shaughnessy (MA 1926; BA 1930; M.Mus. 1935).

Hopefully these lists will help to shine more light on Notre Dame’s pioneer alumnae, as they are an important part of the Notre Dame family and history. There are many other resources available to do further research on these women, such as University Records, Notre Dame publications, and the alumnae directories.

![GPHR 45/4645: Architectural sketch of Lewis Hall exterior, c1962. Drawing by Ellerbe Architects. [copy negative]](http://www.archives.nd.edu/about/news/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/GPHR-45-4645.jpg)

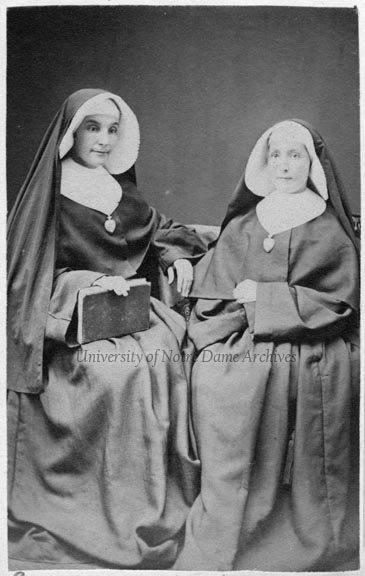

Two unidentified Holy Cross (CSC) Sisters, c1860s-1870s

Two unidentified Holy Cross (CSC) Sisters, c1860s-1870s Mass of thanksgiving in the Holy Cross Sisters’ convent chapel, 1958/0504.

Mass of thanksgiving in the Holy Cross Sisters’ convent chapel, 1958/0504.  Conference of Major Superiors of Women (CMSW), later Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), August 1963

Conference of Major Superiors of Women (CMSW), later Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), August 1963