On June 11, 1917, Notre Dame added a new demographic to its alumni base – women. According to Scholastic, the first two women to earn degrees from Notre Dame did not go unnoticed. During commencement, it was reported that “[t]here was an enthusiastic outburst of applause in Washington Hall when the names of Sister Francis Jerome and Sister Lucretia (Holy Cross Sisters of St. Mary’s College) were read out as recipients of the M.A. [Greek] and M.Sc. [Chemistry] degrees [respectively]” [Scholastic, September 29, 1917, page 6]. The graduation of these two women at Notre Dame was not a one-off occurrence, but rather marked the beginning of a historic tradition of coeducation at Notre Dame. Except for the 1919 commencement, women have graduated from Notre Dame every year since 1917.

The history of coeducation at Notre Dame is a fascinating and complex one. The view of Notre Dame as an all-male bastion often leaves out the story of Notre Dame’s female students who were here before their more traditional female counterparts moved in for the fall semester of 1972. A cursory overview of the commencement programs done in the 1980s gives us a glimpse of these pre-1972 women: 324 bachelor degrees, 4128 masters degrees, 184 PhDs, and 2 law degrees. However, these numbers only tell part of the story.

Going back through the commencement programs today, we gathered more personal information on these women to help humanize them. Many women studied at Notre Dame but did not complete their degrees. They, unfortunately, won’t be on this list, which was created to give a flavor of who these women were. It is for informational purposes only, not to be used as the sole source of serious research. Please contact the Registrar to verify student information.

At the time of this posting, we still have a ways to go to complete this list, but the data gathered thus far is quite interesting. Perhaps there are more laywomen in the mix than what people assumed. Sisters from Saint Mary’s comprise only a fraction of the other orders represented. Notre Dame’s female graduates follows the diversity of the general student population, with women represented from across the country and internationally, including Nova Scotia and the Philippines. The number of multiple degrees the women earned is a bit surprising, as was discovering two triple-Domers thus far: Sister Mary Aloysi Kerner (BA 1922; MA 1923; PhD 1930) and Sister Mary Jerome Shaughnessy (MA 1926; BA 1930; M.Mus. 1935).

Hopefully these lists will help to shine more light on Notre Dame’s pioneer alumnae, as they are an important part of the Notre Dame family and history. There are many other resources available to do further research on these women, such as University Records, Notre Dame publications, and the alumnae directories.

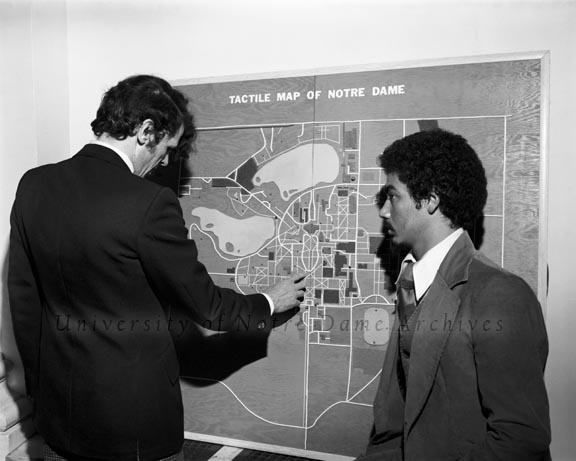

Dr. Stephen J. Rogers Jr. explores a textured campus map as Architecture student Leroy Courseault, who designed and constructed the map, looks on, 1978/0515

Dr. Stephen J. Rogers Jr. explores a textured campus map as Architecture student Leroy Courseault, who designed and constructed the map, looks on, 1978/0515

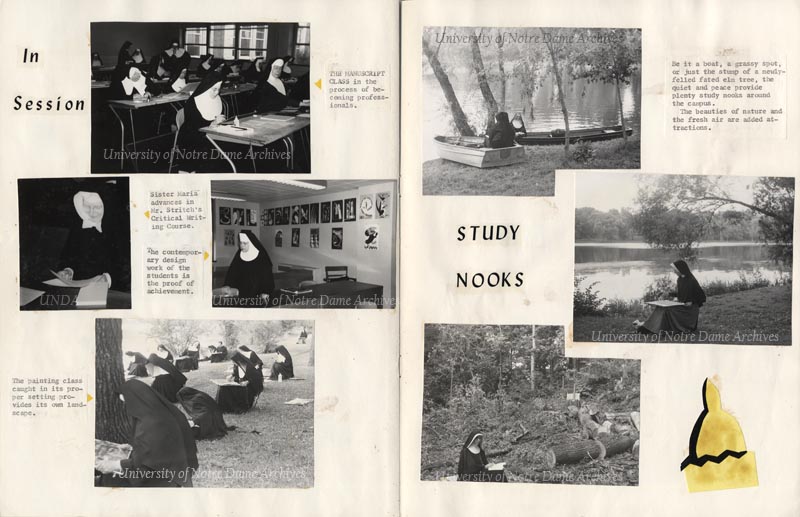

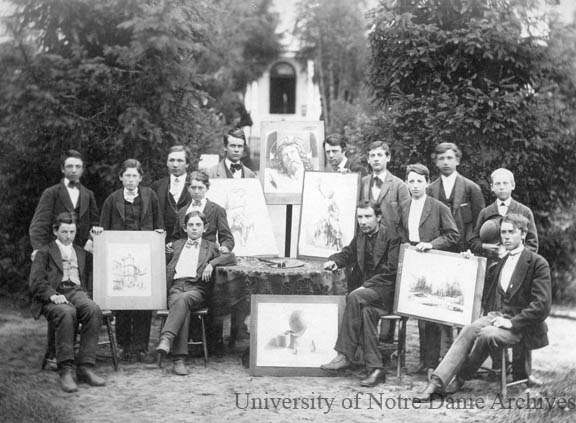

Art class posed outside with their paintings and drawings, c1860s-1870s

Art class posed outside with their paintings and drawings, c1860s-1870s Rev. Anthony Lauck teaching an Art Sculpture Class in a studio in the Main Building, Spring Semester 1953

Rev. Anthony Lauck teaching an Art Sculpture Class in a studio in the Main Building, Spring Semester 1953 Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh and Ivan Mestrovic in an Art Studio, c1960s

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh and Ivan Mestrovic in an Art Studio, c1960s Dr. Maurice Goldblatt, Director of the Wightman Art Collection, beside the fireplace of Francisco Borgia II in the Frederick H. Wickett Memorial Collection, c1933

Dr. Maurice Goldblatt, Director of the Wightman Art Collection, beside the fireplace of Francisco Borgia II in the Frederick H. Wickett Memorial Collection, c1933

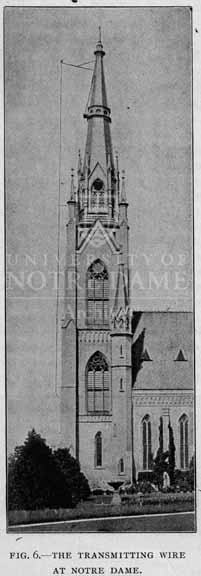

laboratory in Science Hall (now called LaFortune Hall) to other rooms in the building. They succeeded in sending signals from Science Hall to Sorin Hall, then from the flag pole to the Novitiate (which was located near present-day Holy Cross House). “They found that everything worked perfectly well here, and so they set about their last and greatest trial. This was to send a message from Notre Dame to St. Mary’s Academy which is more than a mile away from the University [, using the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for the transmission wire]. … This is the farthest distance a message has been sent in this country as far as we know and the boys in the scientific department feel highly elated over their success.” [Scholastic, 04/22/1899, page 494].

laboratory in Science Hall (now called LaFortune Hall) to other rooms in the building. They succeeded in sending signals from Science Hall to Sorin Hall, then from the flag pole to the Novitiate (which was located near present-day Holy Cross House). “They found that everything worked perfectly well here, and so they set about their last and greatest trial. This was to send a message from Notre Dame to St. Mary’s Academy which is more than a mile away from the University [, using the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for the transmission wire]. … This is the farthest distance a message has been sent in this country as far as we know and the boys in the scientific department feel highly elated over their success.” [Scholastic, 04/22/1899, page 494].