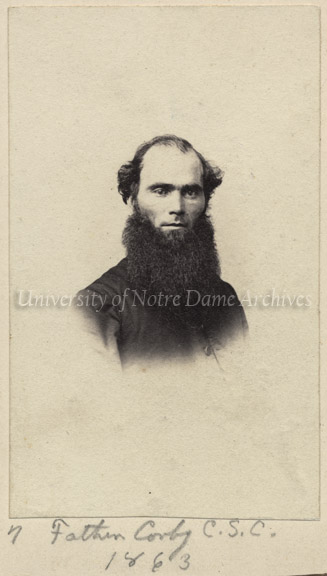

In the autumn of 1861, Rev. William Corby, C.S.C. joined the 88th Regiment of New York as a chaplain in the predominantly Catholic Irish Brigade in the Civil War. Rev. James Dillon, C.S.C., brother to Patrick – another future Notre Dame president, was attached to the 63rd New York regiment, also part of the Irish Brigade. Throughout the entire Civil War, the Irish Brigade was never without at least one priest.

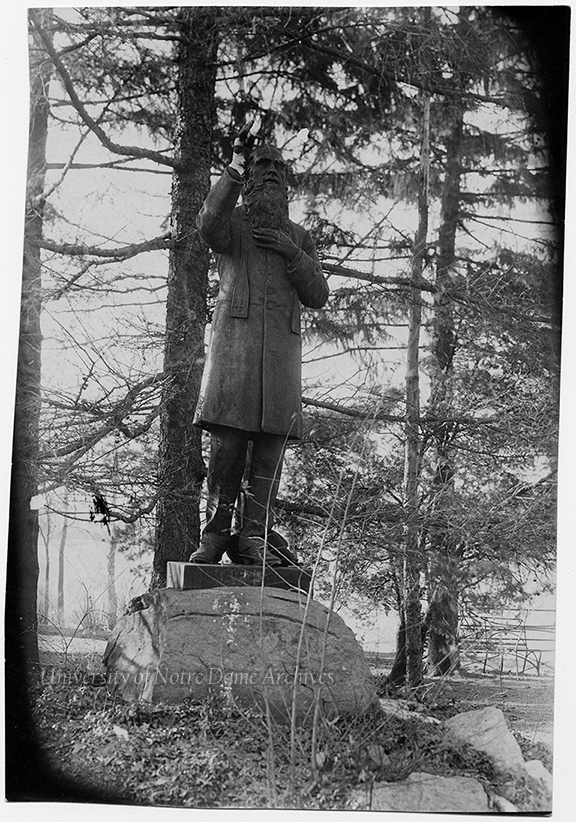

Of all the priests, brothers, and sisters of the Congregation of Holy Cross who served in the Civil War, Fr. Corby is the best-known. At the Battle of Gettysburg, Fr. Corby granted absolution to the troops immediately before they marched into combat, and many ultimately to their deaths. The absolution was later immortalized by Paul Wood’s Absolution Under Fire, currently hanging in the Snite Museum of Art, and by twin statues of Fr. Corby on Notre Dame’s campus and at Gettysburg.

Long after the Civil War, the veterans still held tight to their war stories. Like his compatriots, Fr. Corby kept in touch with other members of his brigade and attended reunions. Additionally, he helped organize the Notre Dame G.A.R. post (nationally noted for being the only one comprised solely of priests and brothers), penned Memoirs of Chaplain Life (1893), and sought artifacts for the museum at Notre Dame.

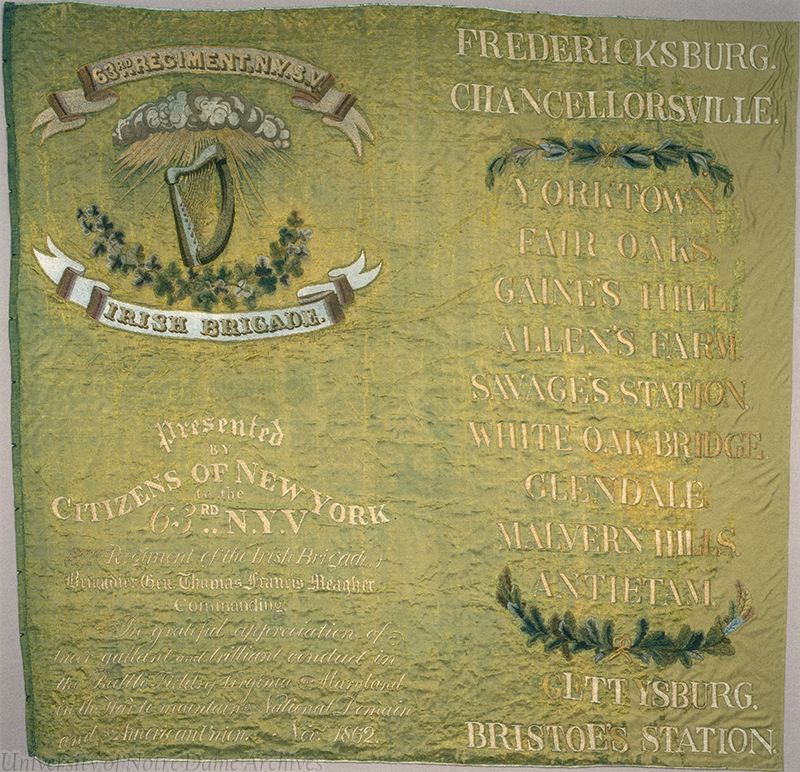

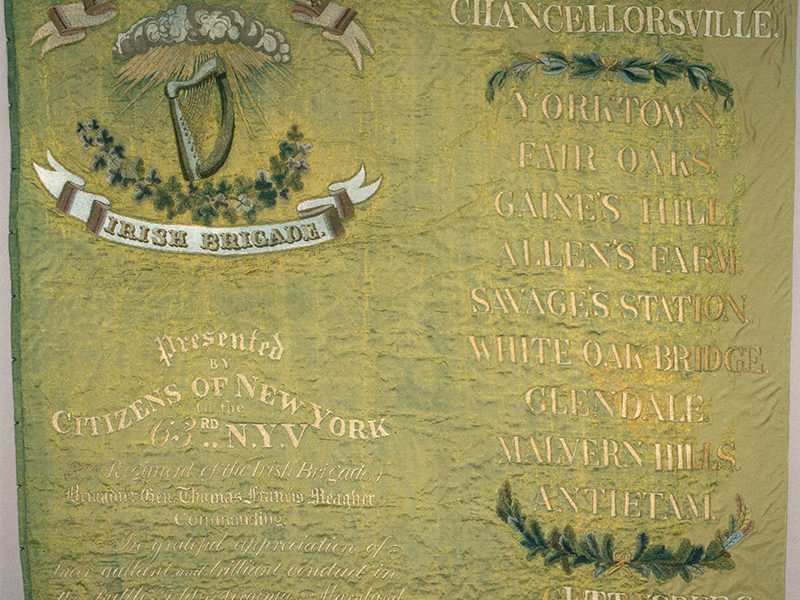

W.L.D. O’Grady, a former captain with the 88th, unsuccessfully worked to collect all of the known Irish Brigade flags and bring them to Notre Dame. He saw Notre Dame as a good central location in the United States, even though the 69th New York National Guard Armory would be a more natural home. The unstated reason was most likely political: perhaps O’Grady didn’t want the flags in the hands of New York’s Democratic political machine. Owner of one of the flags was James D. Brady, a Virginia Republican member of the United States House of Representatives. Brady was sympathy to O’Grady’s cause, and in 1896 he donated to Fr. Corby the Second Irish (Tiffany) Colors of the 63rd New York Regiment.

Brady had intended to visit Notre Dame in order to make a formal presentation of the flag, but his schedule prevented him from doing so in 1896. A year after the flag had arrived at Notre Dame, it must have been clear that Brady was never going to make the trip. James F. Edwards, curator of Notre Dame’s Bishops Memorial Hall, acknowledged the gift to the museum in a monthly circular of donations with no special notice or fanfare.

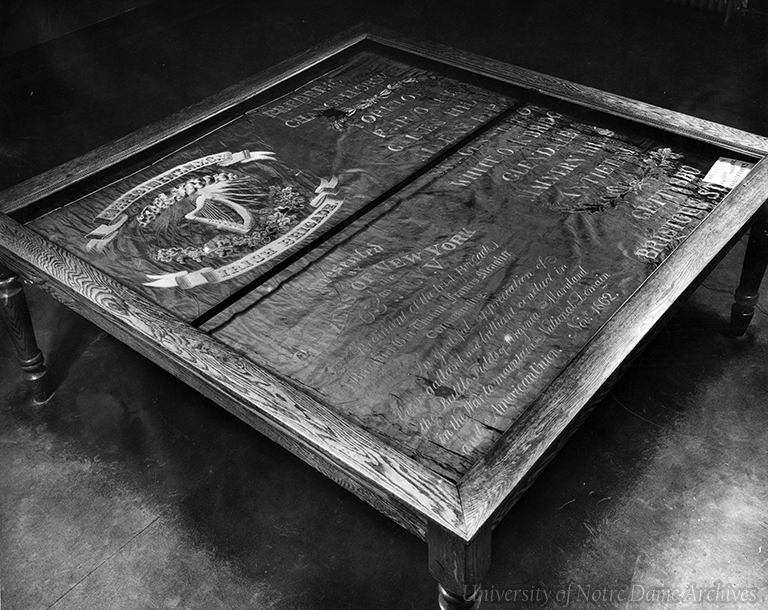

For many years, the Second Irish Colors was on prominent display in Main Building and was relocated to Lemonnier Library (now Bond Hall) when it opened in 1917. From there it moved to the old ROTC building (now West Lake Hall), to the Snite Museum of Art, and to Pasquerilla Hall Center (the newer ROTC building). Finally in 1998, the flag was accessioned into the collections of the University Archives as an important piece of Notre Dame history.

The silk embroidered flag was in rough shape even back in 1896; its tears and holes were falsely assumed to be evidence of the ravages of war. In reality, this particular flag made by Tiffany & Co. was never carried into battle. It was commissioned by prominent New York merchants and was delivered to the Irish Brigade the day after the brigade had lost half of its men at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. The banquet for the presentation of the new colors went on as planned, but ended early on account of renewed Confederate cannon fire.

The soldiers purportedly declined to carry the new colors into battle because the brigade was so depleted that it risked capture. A more likely explanation is that the soldiers preferred to follow a flag presented by the Democrat New York City government rather than one from American-born citizens of the city. General Thomas Meagher took it back to New York City where it was displayed for banquets, parades, and other patriotic events for the remainder of the war. As the last colonel of the 63rd regiment, James Brady took possession of the flag at the end of the Civil War.

Through the generosity of Jack and Kay Gibbons, conservation and restoration work began on the flag in February 2000. The enormous undertaking was completed that September and the flag, mounted and framed for preservation, was first displayed in Notre Dame’s Eck Visitors Center, then on exhibit at South Bend’s History Museum. Due to its delicate nature, the flag must spend years resting in storage after it has been on display for an extended period. However, the Second Irish (Tiffany) Colors of the 63rd New York Regiment is always available for serious scholars to view.

For more information about the Second Irish Colors and the conservation process, please see Blue for the Union and Green for Ireland: The Civil War Flags of the 63rd New York Volunteers, Irish Brigade (http://archives.nd.edu/flag/), by Peter J. Lysy, archivist at the University of Notre Dame.

![Rev. William Corby, CSC, statue at Gettysburg, c1910s "Dominus noster Jesus Christus vos absolvat, et ego, auctoritate ipsius, vos absolvo ab omni vinculo, excommunicationis interdicti, in quantum possum et vos indigetis deinde ego absolvo vos , a pecatis vestris, in nomini Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen" [Corby, page 183]](http://www.archives.nd.edu/about/news/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/GPHR-45-3024.jpg)